Table of Contents

The controversy surrounding the Undergraduate Senate’s call for divestment from “companies that violate international law” in the Palestinian Territories – just formally rejected now and in the future by the Stanford Board of Trustees – is sure to see a resurgence as students vote today and tomorrow. First and most important, many voters have strong views on the divestment debate that will affect their voting, particularly toward candidates endorsed by the actively pro-divestment Students of Color Coalition (SOCC). SOCC has recently been accused of a whole host of allegations surrounding anti-semitism and the Jewish community, including an investigation from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and national media coverage. Second, John-Lancaster Finley, an undergraduate senator who claimed to support divestment “out of love” for Israel and the Jewish community during the first divestment vote, is running for the ASSU Executive. During and before the debate, many members of Stanford’s Jewish community claimed divestment would alienate them on-campus or cause them to feel marginalized. However, these proposed harms have not been substantiated with real data until now.

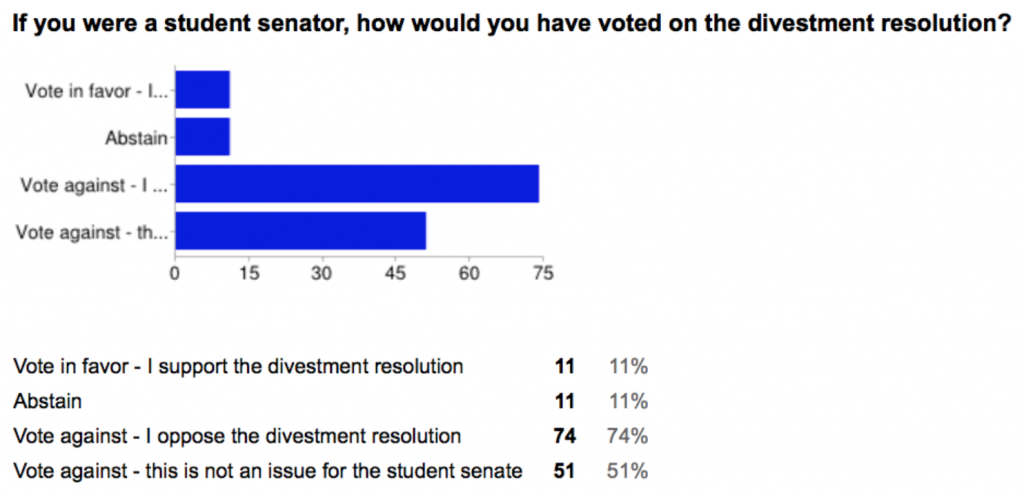

The Review polled the Jewish community to gauge the effect of the Senate’s divestment resolution in early March and received 100 responses, or just under 15% of the Jewish undergraduate population, from self-identifying Jews. We found several trends worth discussing. First, the Jewish community is not monolithic in its views – hardly a surprise to anyone who has ever tried to discuss politics around a Shabbat dinner table. While 74% of respondents reported that they would have opposed the contents of the resolution, 11% expressed support, and 11% would have abstained. Respondents had the opportunity to select multiple responses for this and the next question.

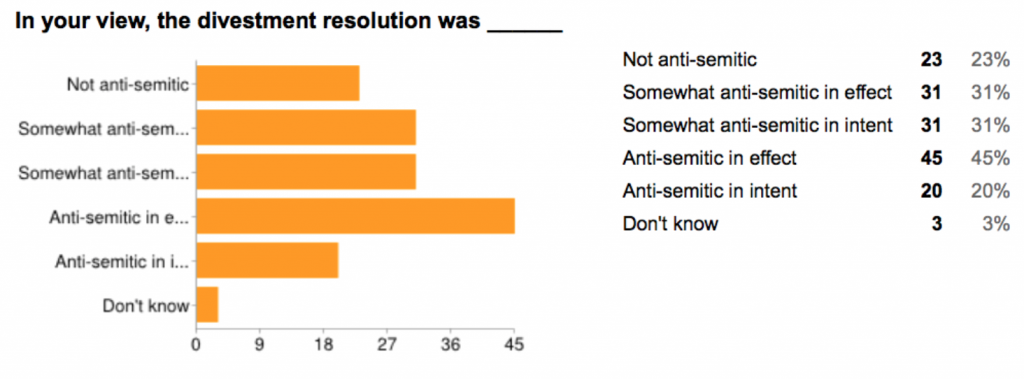

Second, this poll also revealed concerns within the Jewish community about anti-semitism: 20% of respondents called the divestment resolution “anti-semitic in intent.” Moreover, 31% identified the resolution as “somewhat anti-semitic in intent.” 76% were concerned that it was, at some level, “anti-semitic in effect,” to use an admittedly ambiguous term.

That so many people see the ASSU senate’s actions as anti-semitic suggests a deep problem of one form or another. It is simply unhealthy for such mistrust to persist between religious minorities and governing institutions. However, this and the other poll results discussed in this article do not intrinsically disqualify divestment as a policy and the Jewish community’s negative reaction should not, by itself, be wielded by activists to ward off criticisms of Israel. That said, the Jewish community’s fears should be considered in any evaluation of divestment.

Neither the Senate nor Stanford Out of Occupied Palestine’s (SOOP) leadership has made overtly anti-semitic remarks. Yet to dismiss these poll results as merely Jewish paranoia would discount the very real fears of many Stanford students. One of the most respected Jewish columnists in America recently recommended that the Jews once again leave Europe because of the rising tide of anti-semitism, which is also occurring in America. Indeed, anti-semitism rose 400% last year, and a poll from late 2014 found that 40% of American Jewish college students believe anti-semitism is a problem on campus. Moreover, the US State Department’s new definition of anti-semitism includes the ‘Three Ds’ – Demonizing, Delegitimizing and applying Double standards toward Israel – explicitly recognizing the linkage between extreme anti-Israel sentiment and anti-semitism.

SOCC’s alleged conflation of Jewishness and views on divestment in their interview with Molly Horwitz and alleged instructions that candidates not interact with Jewish groups that oppose divestment are perfect examples of this phenomenon. If the allegations are true, then the problem on campus is likely worse than the Jewish community thought. If partly true or even untrue, the magnitude of the reaction to the accusations – both on campus and nationally, with the New York Times reporting – exposes the raw sensitivities and emotions involved.

When SOOP issues a supplementary document accusing Israel of “state-sponsored repression” and sends videos and articles to student groups that accuse Israel of genocide, apartheid, and ‘Jewish supremacy,’ it is not only Israelis who feel isolated. Jewish students see their ancestral homeland becoming the proverbial ‘Jew among nations,’ singled out for special condemnation and vitriol. The principle of going after “the worst first” that has been central to international human rights law seems to have fallen by the wayside for Israel.

The divestment resolution criticizes Egypt and the Palestinian Authority a few times, but its contents are clearly centered around Israeli actions. Indeed, it criticizes specific corporations only because of their cooperation with Israel. Even though many recognize that Israel is the most free and progressive nation in its region and that 77% of Israel’s Arab citizens would rather live in Israel than in any other country in the world, the issue on campuses across America is not whether we should divest from Saudi Arabia or Bahrain, but from Israel.

In response, divestment advocates tend to bring the conversation back to Israel – other countries are other matters, after all. Yet as the divestment campaigns against those other, worse offenders fail to materialize, the Jewish community remains deeply suspicious of the intentions behind divestment. However, not everyone accepts this argument. Many divestment advocates have contrasted the Jewish community’s complaints about divestment with the misgivings of Stanford’s Palestinian community concerning potentially funding oppression in their homeland. Moreover, if Israel wants to be a western-style democracy, it may have to be held to a higher standard than the autocracies in its region.

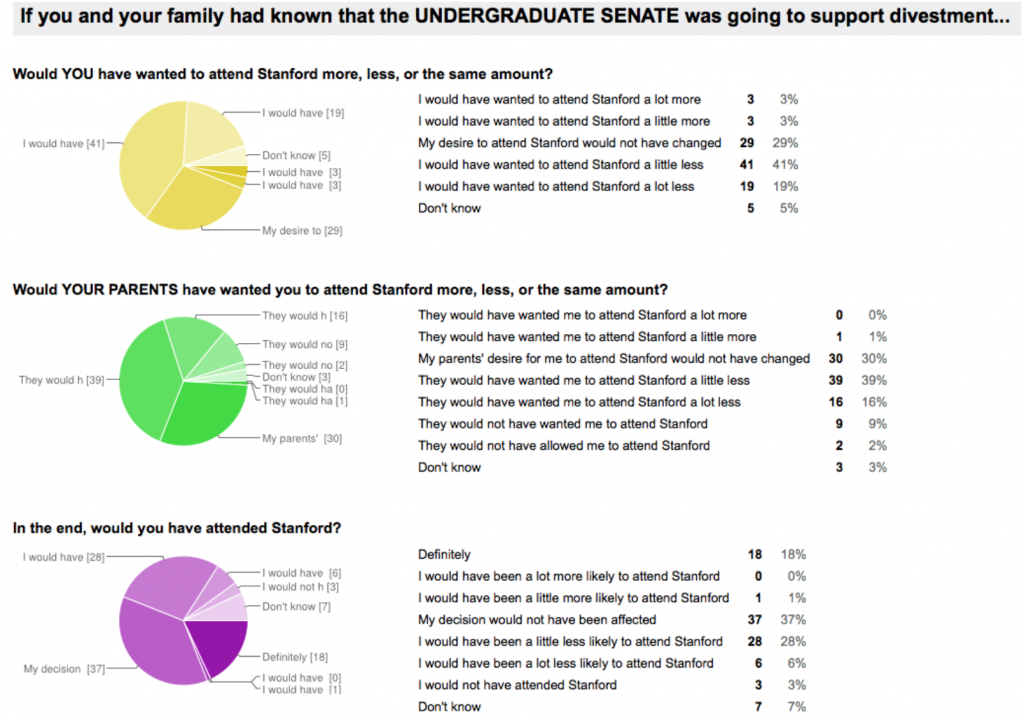

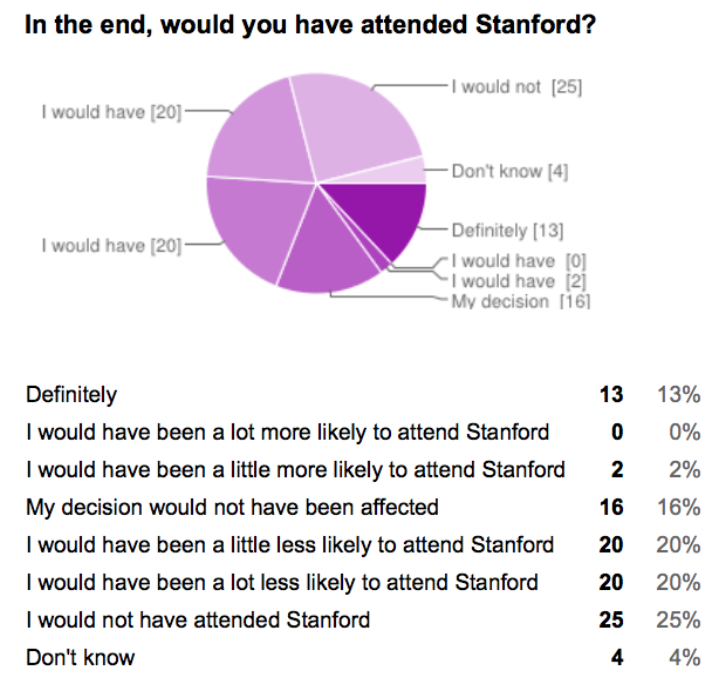

There are arguments on both sides, but the crossfire may cloud the effect of the Jewish community’s reaction to divestment. Exactly 60% of respondents to the Review’s poll answered that the Senate’s decision to recommend divestment would have made them personally want to attend Stanford less. When asked “In the end, would you have attended Stanford?” 37% reported that they would have been less likely to attend, to varying degrees.

The data suggest that the Jewish community’s fears of divestment do not exist in a vacuum. Some qualified, talented Jewish students may choose other top schools over Stanford in the future, or they may not apply to Stanford at all. In these scenarios, Jewish students lose out on Stanford’s unique opportunities and Stanford misses out on exceptional students and their rich cultural heritage.

Furthermore, Stanford has rejected the student senate’s call for divestment through both President Hennessy and the Board of Trustees, likely moderating these poll results. But if the undergraduate senate called for divestment, surely it must be accountable for the consequences of its proposed policy. Thus, let’s imagine that the Board of Trustees had heeded the counsel of the ASSU, and the university actually did divest from Caterpillar, Lockheed Martin, and the rest of the companies. When offered this hypothetical in which the university had actually divested before they had come to Stanford, what did the Jewish community respond?

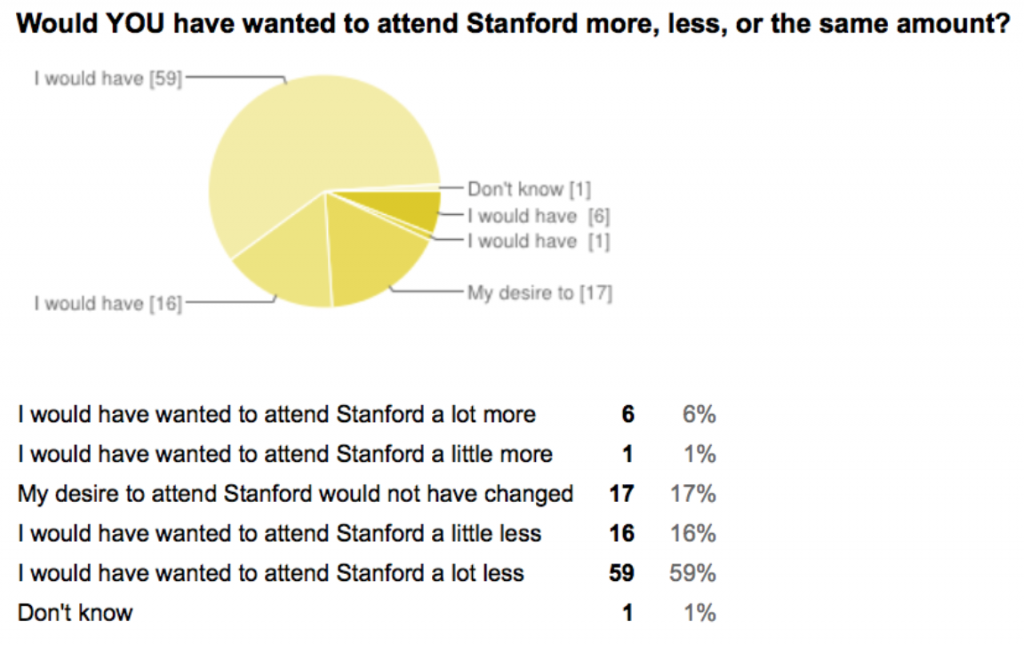

A whopping 59% of respondents report that “I would have wanted to attend Stanford a lot less.” 16% selected “a little less.” That’s 75% of respondents discouraged from attending Stanford.

As a result, 25% of Jewish students are certain they would not be here if the university had formally divested, and a further 40% would have been less likely to attend. Moreover, these results concern Stanford, the #1 ‘dream college’ in America, a fact that most likely would keep many disturbed Jewish students from reacting more strongly.

Like any attempt to examine counterfactuals, these last poll results must be met with a healthy dose of skepticism, but it seems that the extraordinary results speak to a larger issue: perceived anti-semitism. Even if the senators’ intent was purely one of ‘love’, as John-Lancaster Finley so misguidedly put it, it should not matter. The results may suggest that the ASSU’s recommended policy would have, in effect, excluded some Jews from Stanford, and discouraged many more from attending the University.

The Board of Trustees concluded in part that divesting would cause “deep divisions within the University community,” as the Statement on Investment Responsibility puts it. The results of this poll, viewed in combination with the context of global anti-semitism and the massive response to the recent allegations against SOCC, proves the Board’s point.

SOOP leaders may well respond that taking action against South Africa likely also dissuaded some Afrikaners from coming to Stanford, and they would not be wrong. It should be again noted that neither the Jewish community’s reaction nor their situation on campus inherently form arguments against divestment. However, the vast majority of Stanford students are not divestment activists and are unconvinced that Israel is the moral equivalent of apartheid South Africa. These students should make informed decisions when they vote in ASSU elections and consider the harms that divestment may inflict upon the Jewish community.