Table of Contents

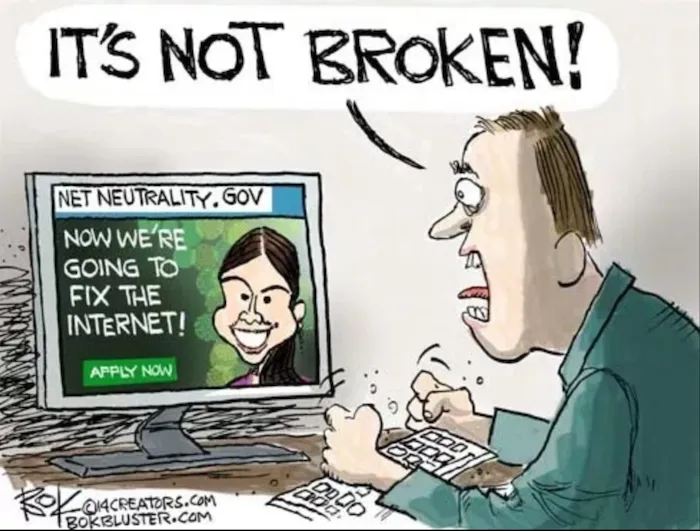

Last week, Trump-appointed FCC chairman Ajit Pai announced his plan to repeal the Obama administration’s net neutrality regulations. Pai claims the plan will return the Internet to the “free market consensus” that prevailed for years, “putting engineers and entrepreneurs, instead of bureaucrats and lawyers, back in charge of the internet.”

Silicon Valley immediately struck back in opposition. Google, Facebook, and Netflix immediately released statements condemning the proposed changes. Even Stanford students opposed the proposed legislation. Concerned students posting in the Facebook group “Stanford Memes for Edgy Trees” urged classmates to call their representatives in Congress to condemn the FCC’s plans.

Throughout the uproar, few in Silicon Valley have stopped to question whether net neutrality might be flawed, despite the fact that 44% of economists oppose it and a full 36% remain uncertain.

Here in Silicon Valley, asserting that net neutrality might not be best for the Internet is taboo. But while Stanford students and technology corporations might be well-intentioned, their advocacy for net neutrality is misguided.

The principles of net neutrality requires that Internet service providers (ISPs) like AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon treat all data the same: in other words, they may not speed up, slow down, or block any content, applications, or websites. The Obama administration enshrined this principle in law with the 2015 Open Internet Order, which determined that the Internet would be regulated as a public utility by the Federal Communications Commission.

While net neutrality is attractive in theory, regulating the Internet in this manner harms consumer choice and stifles innovation. Unlike other industries that have historically been regulated as public utilities, the Internet is not controlled by a single monopoly: according to the FCC’s data, nearly seventy percent of American households have a choice among three or more wired providers, including cable and telephone companies, and twenty percent of US consumers switch networks every year. A report by the US Department of Commerce reveals that at download speeds of three megabits per second (Mbps) — the FCC’s current approximate standard for basic broadband service — ninety-eight and eighty-eight percent of the population respectively had a choice between at least two mobile and fixed ISPs.

The internet is an essential service. It is not, however, a monopoly that must be classified as a “public utility.” Food, clothing, and shelter are likewise essential, but to regulate them has public utilities would be ridiculous.

Furthermore, treating the Internet as a public utility would threaten continued technological innovation. Industries regulated as public utilities have historically stagnated because they become less competitive and harm consumers in the process. America’s infrastructure is a prime example: it is estimated to require at least $3.6 trillion in repairs, and was recently given a D+ rating by the American Society for Civil Engineers. Sixty-two percent of gas mains in Washington DC are more than 50 years old!

While Congress treated the telecoms as a public utility like infrastructure, in the early days of the Internet, Congress allowed fixed and mobile broadband access markets to develop on their own.

The result? Internet companies have been forced to innovate at a rapid rate to keep up with competitors. The United States has seen nearly one and a half trillion dollars in private investments for cable, mobile, fiber, and next-generation copper/fiber hybrid services. Eleven of the world’s top fifteen Internet businesses, most of which were started in the last decade, have come from the United States.

The US government has historically suggested a litany of backward Internet policy ideas. The first FCC petition after the invention of voice-over-IP services, which allowed users to “talk” over the internet, argued for declaring VoIP software illegal. If the Internet had been subject to the FCC’s Title II telecom regulations, voice-over-IP services like Skype, FaceTime, and WhatsApp might not exist!

Finally, the Obama-era regulations fail at their own purpose: they do not even adhere to the founding principles of net neutrality. Though Tim Wu, who coined the term “net neutrality,” stated that “a total ban on network discrimination would be counterproductive,” this is exactly what today’s supporters of net neutrality advocate for. The Open Internet Order, furthermore, featured a glaring loophole that prevented the regulation from satisfying hardliners and skeptics. Under the law, ISPs that curate their experience and provide “edited” content are not subject to net neutrality rules. This means that ISPs are free to create fast and slow Internet lanes as long as they inform their customers that they are doing so, a practice antithetical to the principles of net neutrality.

In 2005, Harvard Law professor Susan Crawford stated that she had “lost faith in our ability to write about code in words, and [was] confident that any attempt at writing down network neutrality [would] be so qualified, gutted, eviscerated, and emptied that it [would] end up being worse than useless.” Silicon Valley justly laments the lack of technical literacy in government. Classifying the Internet as a public utility would grant technologically illiterate Washington lawyers and elected officials far too much control over the technology industry. Solutions like local loop unbundling which promote competition would be far more helpful than net neutrality.

The Internet did not flourish because of entrepreneurial politicians and five-star government customer service. Subjecting it to a decades-old ruling intended for landline telephone companies will only slow the innovation that has characterized the Internet since its inception. Does it really make sense to subject the Internet to a regulatory regime established for phone companies in 1934?