Table of Contents

It is no secret that Stanford is overwhelmingly liberal, with 93% of voters breaking for Biden in the postcode 94305. While this reflects the values of many students and faculty, it raises important questions about how such homogeneity might affect the range of perspectives presented in academic discussions. Stanford’s mandatory programme in writing and rhetoric (PWR) tasked with instructing students in writing is case in point.

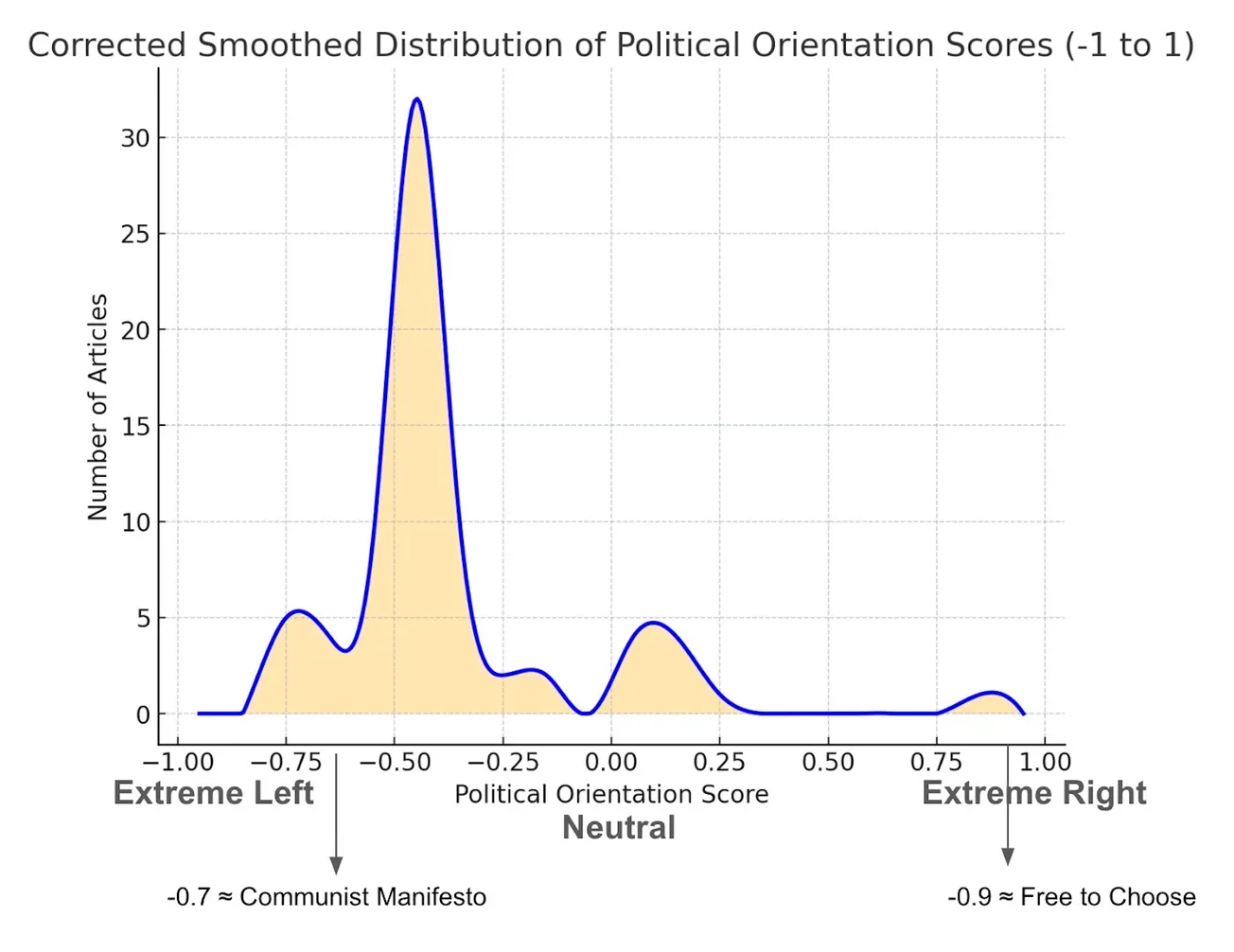

In order to better evaluate bias in course materials presented in these mandatory and introductory classes I compiled all available PWR syllabi from 2024 to 2025, including 306 assigned readings. I then asked the ChatGPT 4.0 model to give each assigned reading a political orientation score. What I found was shocking:

First for some context, under the PWR programme students are mandated to choose from two classes over their freshman and sophomore years. These classes include ‘The Rhetoric of Plants,’ investigating “how plants can be a markers for social inequality,” The Politics of Pleasure, Love and Joy,’ where students explore “the politics of sexual pleasure, heteronormative structures of joy, decolonization of joy, and love under capitalism,” or the ‘Rhetoric of Ethnic narratives’ to learn “how biracial and bicultural people define their ethnicity.”

The vast majority of PWR classes adhere to the leftist philosophical tradition of critical theory. While these publicly available quotes barely scratch the surface of the ideological orthodoxy, the reading material that I analysed is even more radical, as it is the private and thus more representative version of these classes.

To determine the political orientation scores I gave each assigned reading a political orientation score between -1, representing radical left, and 1, representing radical right. Neutral readings (rated 0) were excluded as they were primarily scientific or factual. I also excluded 0’s as the A.I. mistakenly included research assignments when it was scraping the syllabi. After removing all zero scores, the mean political orientation score is approximately -0.51, and the median score is -0.5. For context, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto is rated -0.7, and Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose is rated 0.9.

Approximately 15% of assigned readings were greater or equal to the Communist Manifesto in their left leanings. 22.5% of readings were rated -0.5 and lower in their political orientation, representing extreme left wing viewpoints, while there were virtually no right-leaning readings offered in any PWR courses. Out of the 306 readings, ~1.19% of the readings have a score greater than or equal to 0.2, representing mildly right leaning viewpoints. Meanwhile, ~22.5% of readings were estimated to rely on critical theory according to the model.

Attached: PWR 1 Readings, PWR 2 Readings

Notably, the issue is not that we are having discussions involving oppression, inequality and anti-imperialist perspectives on the indigenous communities' use of psychedelics. (which are all real class discussions). Nor do I have a qualm with the quality of instruction: PWR lecturers are dedicated and eminently intelligent. The issue arises when the only topics and conclusions PWR deems worthy of teaching are aligned with the unique philosophical tradition of critical theory and grievance studies. When alternative centrist viewpoints and opposition to extreme views are bereft from curricula, PWR devolves into radically progressive opinions masquerading as mandatory introduction to writing and research classes.

Ultimately, mandatory PWR classes are the catalyst for assimilating frosh who otherwise enter Stanford with diverse political opinions into the campus political monolith. For many, myself included, PWR is the first class students take at Stanford. It therefore leaves an unmistakable impression on what is required of you and what to expect from Stanford.

My very first class was PWR 1, where we read ‘Cracks in the Iron Closet: travels in gay and Lesbian Russia.’ This book involved a graphic and academic discussion of casual gay sex in the Soviet Union. It quickly becomes clear that certain academic viewpoints, particularly those of an anti-Western, progressive bent are preferred. Those that reject viewing society primarily through the lens of oppression and critical constructivism have little hearing. As one of the first opportunities for students to engage with academic discourse, they could benefit from a more diverse array of viewpoints to reflect the broader spectrum of intellectual traditions.

Most worryingly, for many STEM majors PWR is their primary academic discussion of the humanities and questions of morality. Hence, they are likely to take the assigned readings of PWR as the virtuous consensus of Stanford’s collective cultural ideal. Then carrying this expectation into their peer groups, they maintain the dominance of PWR’s strain of critical theory. With that PWR quickly sets the tone for the hegemonic goodthink at Stanford over the next four years.

It appears the time-tested Socratic dialectical method, where questioning and dialogue exposes contradictions in viewpoints, leading to deeper understanding, has been all but abandoned in these classrooms. While faculty are dedicated and highly knowledgeable, the current curriculum does not provide students with the full range of perspectives necessary for independent critical analysis.

Image courtesy of the ‘Rhetoric of Satirical Protest’ Syllabus

Above is an image from the syllabus of a PWR class entitled ‘The Rhetoric of Satirical Protest,’ comparing Trump to toilet paper. In this class students “propose a research project that explores some aspect of satire as a form of protest.” The syllabi employs jokes such as the one above to compare Trump’s efficacy to toilet paper, mock anti-abortionists, decry MAGA and those against mask mandates. With the stated emphasis on “using humor to root out classism,” and oppression. Again, it appears only certain forms of humor that align with certain political persuasions are permissible. Notwithstanding, the peculiar necessity to mandate such a class, the academic rigor would be improved if humor that both accepts and protests the right were present.

PWR is an introductory class where students lack the requisite knowledge to question assigned readings. Thus, the resolution of this issue involves teaching a host of viewpoints and facts more representative of academia’s many schools of thought. Ultimately, If students are not provided critiques to the dominant viewpoints presented how can they not but comply? When assigned readings provide diverse viewpoints students can critically analyse information for themselves enabling genuine discussion and academic exploration.

If the Western canon and classical conceptions of critical thinking were more universally taught, PWR students would likely realize the infamous aspiration of John Stuart Mill encapsulated in the lines “He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side, if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion.”

We cannot maintain the platitude that there is still room for debate when we overwhelmingly teach one set of opinions and facts in introductory classes. By broadening the range of perspectives in PWR classes, Stanford has an opportunity to foster a more inclusive and robust intellectual environment. This would not only enrich students' understanding but also uphold the university's commitment to rigorous and open academic inquiry.

Images courtesy of select PWR Syllabi: