Table of Contents

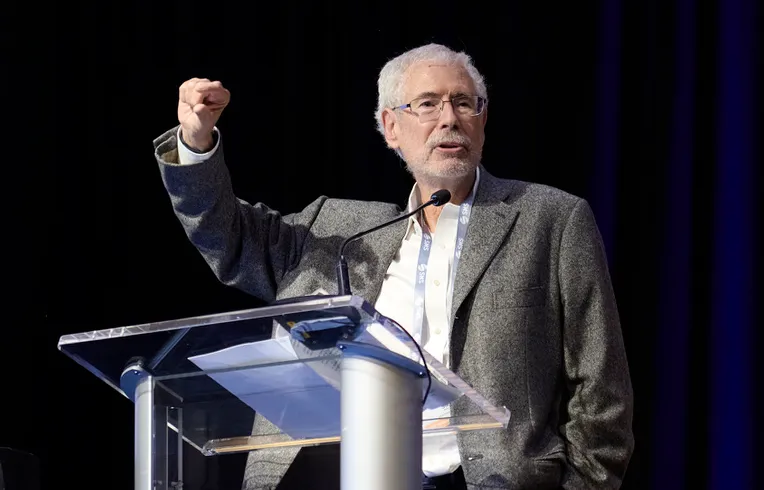

In a September 23 visit to the Hoover Institution, Brazil's Chief Justice Luís Roberto Barroso shared his questionable outlook on Brazil's judicial system and the tumultuous political landscape. While visiting, Barroso presented himself and the court as stalwart defenders of democracy in the light of attacks launched by supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro. However, his actions and proposals in Brazil—as well as his speech at Stanford—reveal a concerning pattern of judicial activism and overreach.

Barroso began his speech with a startling revelation: Brazil's constitution is so expansive that it places matters that would typically be left to the legislative branch into the jurisdiction of the courts. The Brazilian constitution has over 65,000 words, across a staggering 250 articles! That’s almost ten times as long as the U.S. Constitution, which has only seven articles. The Brazilian constitution regulates matters as disparate as education, health, work, social security, parental rights, and more, topics usually left to the discretion of political branches in other countries.

This built-in constitutional overreach, while perhaps created with good intentions, blurs the lines between governmental branches and, worse yet, puts an enormous amount of power into the hands of unelected judges. The backlog of over 80 million pending cases the Supreme Court faces, with an additional 35 million new cases filed annually, underlies this overreliance on a judiciary drowning in its own authority. Yet, Barrosso’s focus seems to be on further expanding the court's vast power rather than addressing these fundamental inefficiencies.

There is perhaps no clearer example of this than the court's recent decision to ban X. The order to ban the platform came after a long-running dispute with the Brazilian authorities over the failure to take down accounts accused of spreading disinformation, including that of Senator Marcos do Val. Those caught using VPNs to access X will face fines equivalent to $9000 USD a day—a prime example of the high price the judiciary is willing to set to prevent anyone from accessing the platform. If an unelected judge (in this case, Alexandre de Moares, who acted unilaterally before his decision was unanimously approved by other judges) can ban a platform for refusing to silence the speech of a political rival on one of the most prominent social media platforms, is this not the very definition of tyranny?

In his visit to Hoover, Barroso expressed no qualms with silencing political speech in the name of safety of “democracy” and didn’t even respond to any criticism against de Moraes' decision, a troubling move given international criticism against Brazil’s revamped censorship regime which faces no oversight.

Following Bolsonaro’s electoral defeat, the Supreme Court took on a troublesome trend towards the prosecution of political opponents. On 8 January 2023, a mob of Bolsonaro’s supporters attacked Brazil's federal government buildings. The court’s plea bargain offers to convicted protesters consisted of social media bans and mandatory "democracy courses". Because when has state-sponsored re-education ever gone wrong?

The fact that less than half of those arrested on January 8 have accepted these terms suggests a profound mistrust in the judiciary's motives and methods, especially when the government has barred Bolsonaro from running for public office until 2030. When Barroso mentioned this plea deal in his Stanford speech as if it was a slap on the wrist for protestors, the idea that government propaganda could be morally objectionable never seemed to occur to him.

Equally concerning is Barroso's advocacy for affirmative action within the judiciary. In his visit to Hoover, Barroso advocated measures forcing gender parity on the courts as well as increased racial diversity. As with any affirmative action program, this approach prioritizes diverse representation over merit and qualifications, and his emphasis of this issue during his speech at Hoover while Brazil faces a plethora of pressing problems demonstrates his disconnect with the Brazilian populace. Such a policy stands to further undermine public confidence in the competence and impartiality of the courts, at a time when trust in institutions is already at concerningly low levels.

As Brazil attempts to work its way back to normalcy after years of political upheaval, it must reassess the role of the judiciary and restore proper separation of powers between the branches of government. The long-term health of the nation's democracy requires a judiciary that respects its limitations as much as it exercises its authority. Barroso's vision of an activist court, as he illustrated at Hoover, may inadvertently undermine the very foundations it seeks to protect.

In the United States, attempts at censorship and the suppression of “disinformation” launched during the COVID-19 pandemic and the aftermath of the January 6th riots previewed the dangers of government intervention in the regulation of internet speech. Silicon Valley and Stanford have both been captured at the heart of this struggle. Stanford professor Jay Bhattacharya was named as one of the plaintiffs named in a Supreme Court case against the Biden administration’s collusion with social media giants, and Mark Zuckerberg revealed that Facebook was pressured to remove satirical content on COVID-19.

With much less stringent free speech protections than the U.S., Brazil provides a cautionary tale of the dangers of an over-emboldened judicial system when combined with a federal government bent on silencing dissent. America would do well to take Barroso’s visit to Stanford as a dire warning, instead of a how-to guide, on the protection of democracy and free discourse.