Table of Contents

On January 29th, the Undergraduate Senate emailed all Stanford undergraduates announcing a "Joint Resolution in Solidarity with the Nationwide Student Strike and Opposition to Federal Immigration Enforcement Violence." The Associated Students of Stanford University is in violation of its own constitution. It has no authority to represent positions on national political issues while speaking on behalf of Stanford students.

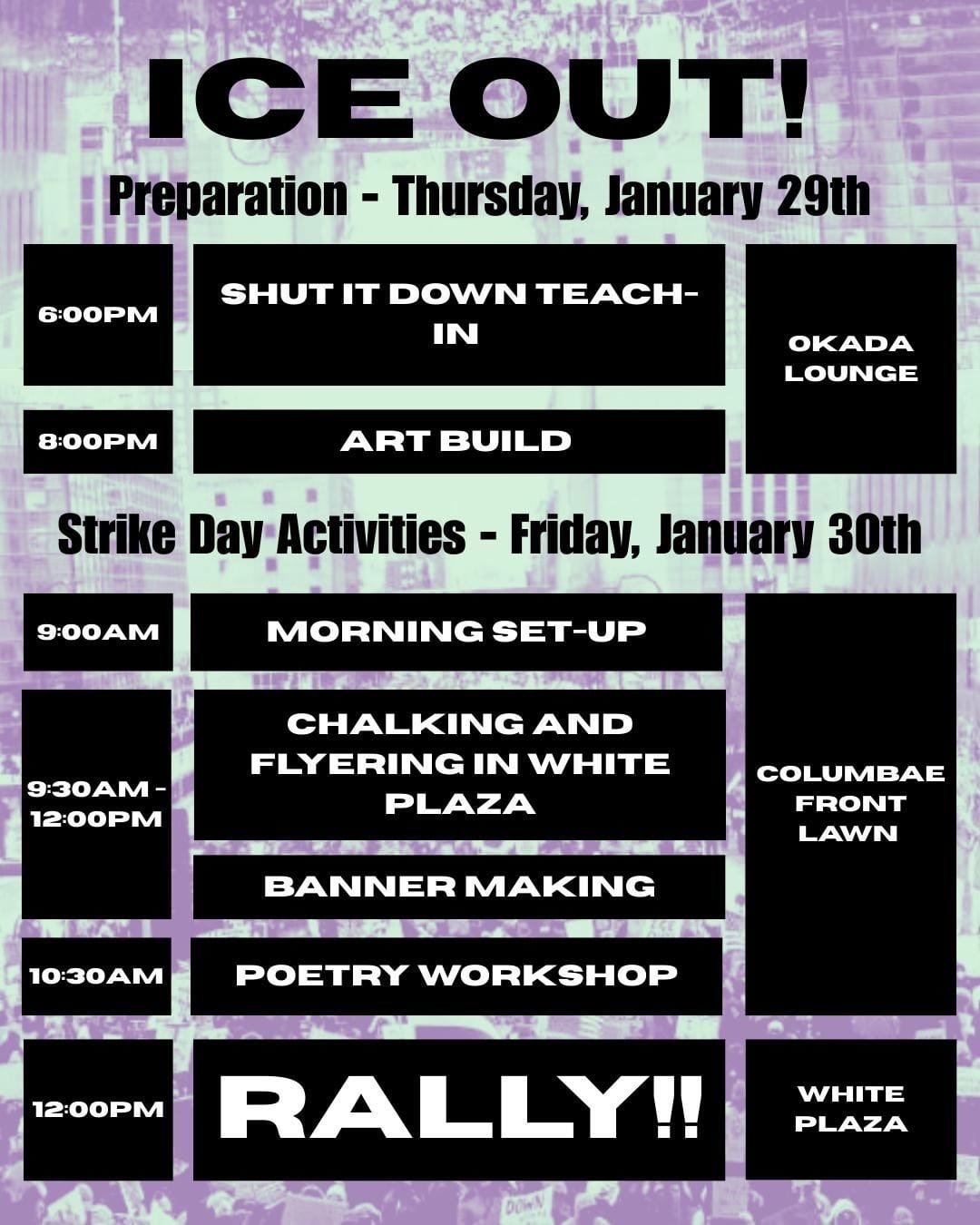

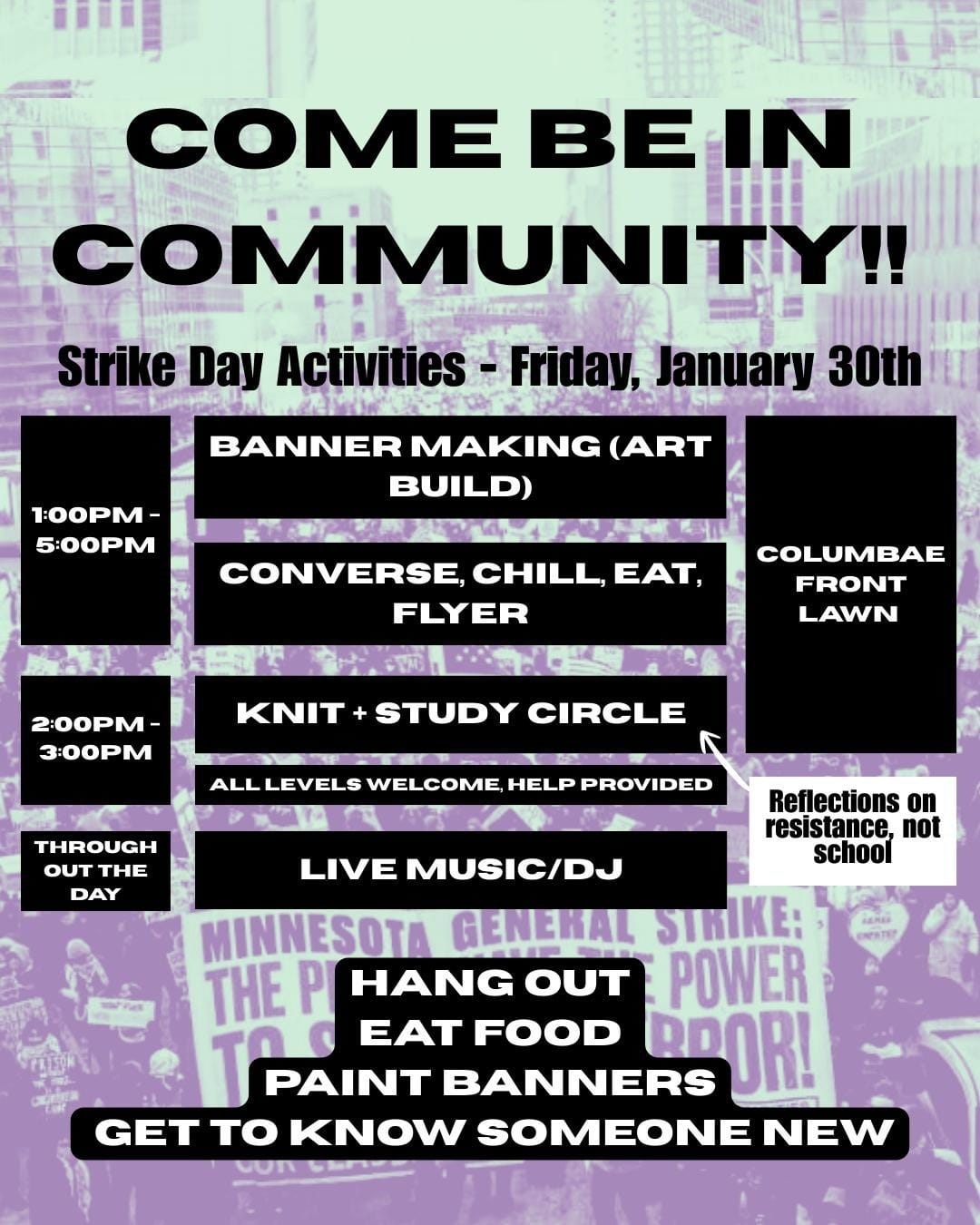

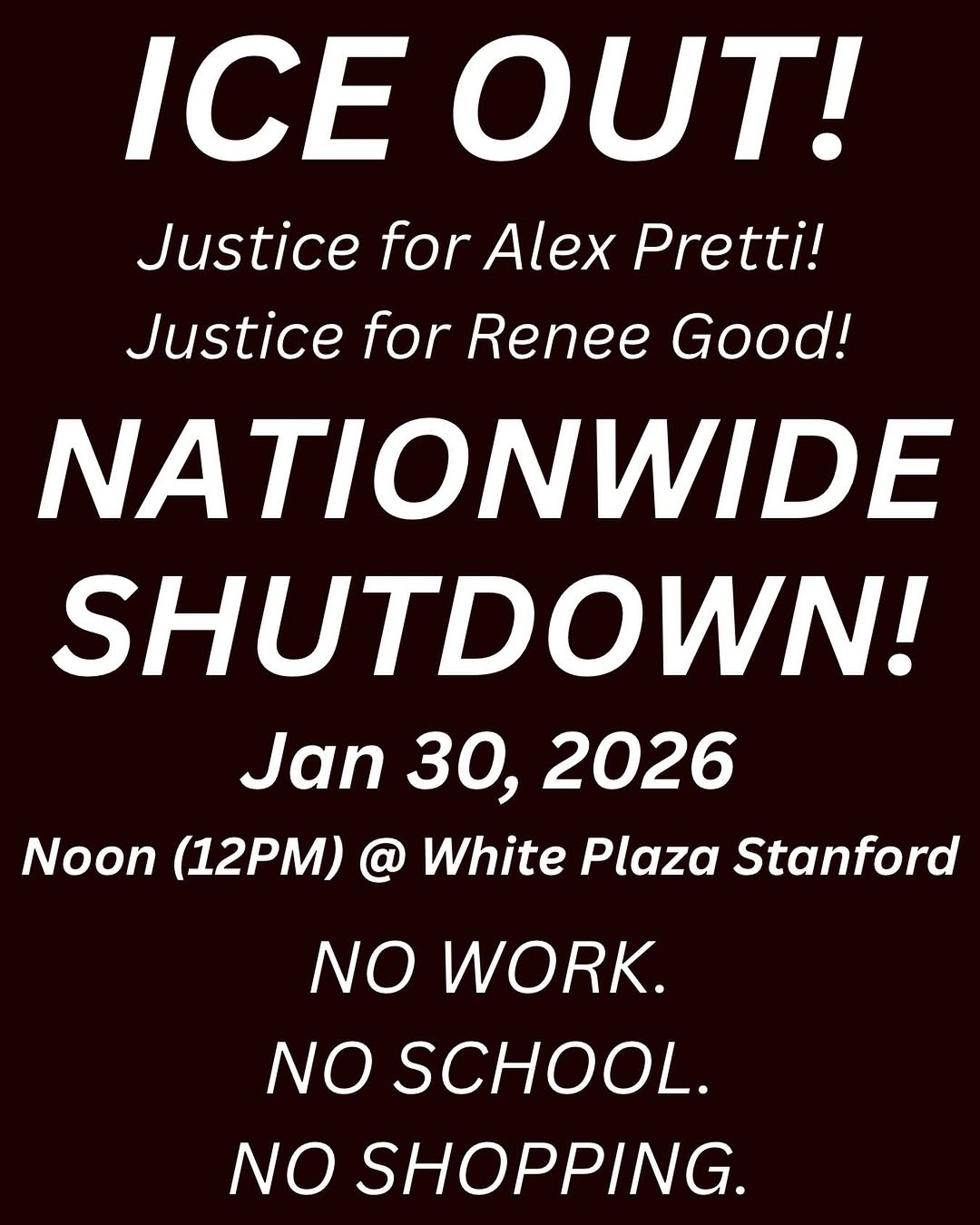

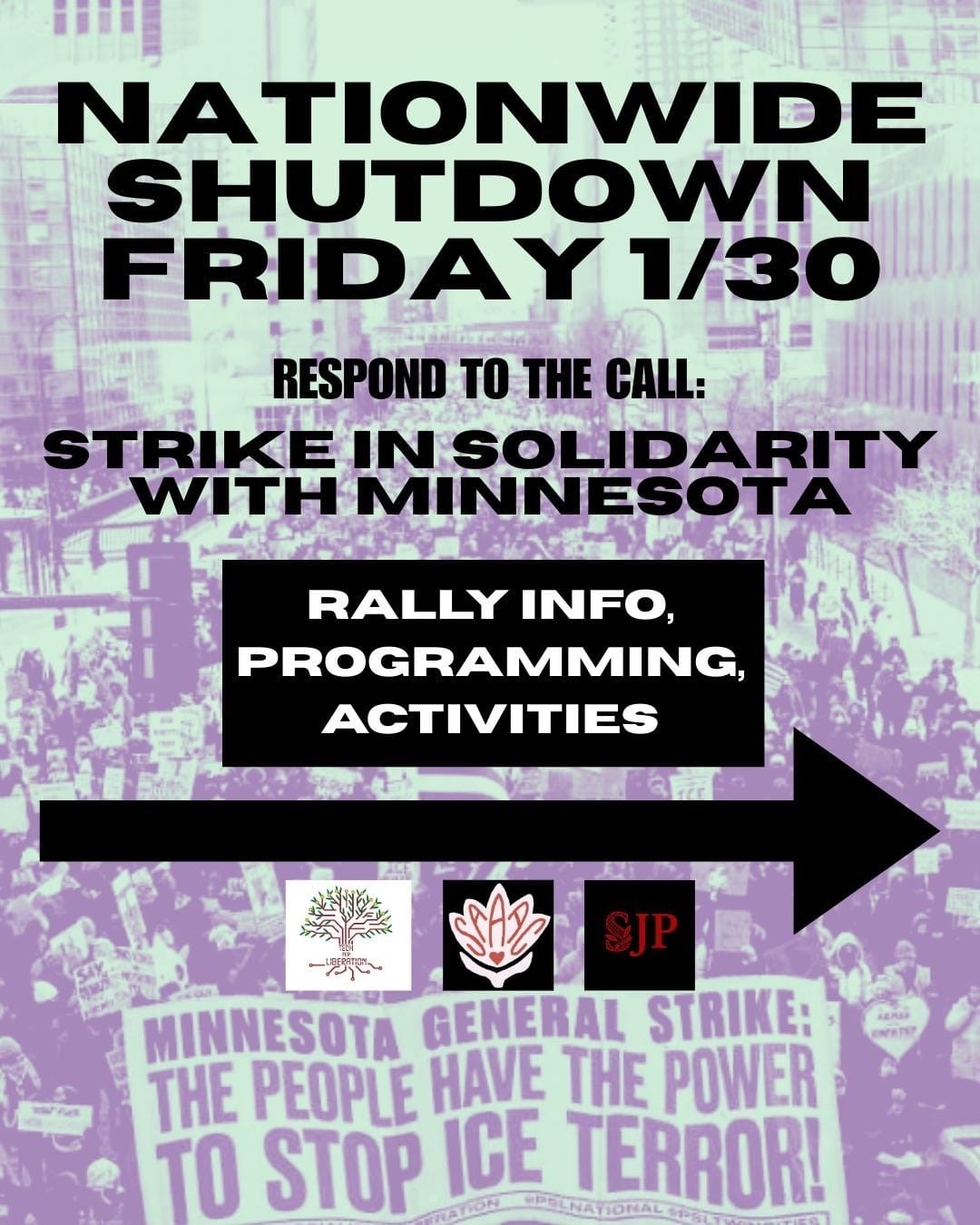

The resolution, endorsed by over 50 student organizations, was passed unanimously by the Senate and 11-0-2 by the Graduate Student Council. It calls for investigations into two deaths caused by ICE operations in Minneapolis and expresses solidarity with a nationwide protest movement, strongly encouraging students to join a campus walkout on January 30th. Attached to the email are promotional flyers with the slogans "ICE OUT!", "NATIONWIDE SHUTDOWN!", and "NO WORK. NO SCHOOL. NO SHOPPING."

Article I, Section 5.B of the ASSU Constitution, which governs the right of the ASSU to represent students outside of dealings with the university, states:

“No Association governing body, including the Association legislative bodies…shall exercise this right in matters not directly affecting Stanford students. A matter shall be construed as directly affecting Stanford students only if there is at least one Stanford student who is affected by the matter in a substantially different manner than would be the case if he or she were not a university student.”

The resolution asserts that “Many students at Stanford—especially those from immigrant and mixed-status families and communities of color—have expressed that these events are not remote headlines, but sources of fear, grief, and instability that directly affect our peers and our campus.” Quoted in the Daily, Senate Chair David Sengthay further explained that “the actions of ICE and federal immigration enforcement agencies directly implicate these issues by contributing to fear, trauma, and material harm within our student body and the communities they come from.”

The constitutional standard requires not just that Stanford students are affected, but that they are affected in a “substantially different manner” than non-students. Being a Stanford student must create a differential impact. Here, there is no evidence that it does.

Students from immigrant families have no doubt experienced fear, in line with national polling showing sharp increases in immigration-related concerns. Yet those effects are not a product of being a Stanford student. A Stanford student who is undocumented is affected by immigration enforcement because they are undocumented, not because they are a Stanford student. The Constitution does not authorize the ASSU to speak for all undergraduates whenever some undergraduates belong to a group affected by federal policy. Immigration enforcement in Minneapolis has no established student-specific nexus to Stanford.

None of this bars the Senate from supporting affected students through constitutional means. Students on F-1 visas or with DACA status do face enrollment-dependent immigration vulnerabilities, so a resolution advocating for university legal services, emergency resources, or regulatory protections for these students would likely satisfy the constitutional standard.

But this resolution does not do that. It calls for investigations into deaths in Minnesota and encourages participation in a nationwide political action. The constitutional defect is not the Senate's reasonable concern for immigrant students; it is the claim of authority to speak for all undergraduates on federal policy that affects Americans regardless of enrollment.

One provision of the resolution, urging “the University to respect student rights and refrain from punitive or retaliatory action against students who participate peacefully,” is a proper exercise of the ASSU's authority to represent students in dealings with the University. But it is bundled with external political content that fails to meet the constitutional standard.

The Senate Bylaws define a resolution as a “bill in support or opposition of a position” whose “purpose is to voice the [Undergraduate Senate]’s support of a particular cause” and require resolutions to include constitutional analysis under Article I, Section 5. The resolution does cite the constitutional standard, quoting the "directly affecting Stanford students" language and asserting that federal immigration actions "directly implicate these interests by contributing to fear, trauma, and material harm within the Stanford student body." But this analysis is conclusory, claiming compliance without demonstrating how the differential impact test is satisfied. The Senate also suspended the prior-notice requirement for the resolution, foreclosing any opportunity to raise constitutional objections before passage.

The Constitution does provide a path for external political statements. Article I, Section 5.B allows a two-thirds referendum vote in a general election to authorize the ASSU to act on a specific issue outside the university for one year. But no such referendum was held, for immigration policy or anything else, on the 2025 ballot. A unanimous Senate vote cannot substitute for the consensus of the student body.

The Senate bypassed this mechanism. If the resolution stands unchallenged, future Senates could issue political statements on any national issue, be it elections, court decisions, foreign policy, or the Federal Reserve changing interest rates, by the simple two-thirds vote of senators present needed for a resolution, without student authorization. The referendum requirement would become optional.

The question is not whether students or senators may hold political views or walk out for whatever cause they like. It is whether elected representatives are bound by constitutional restraints or can claim to speak for all undergraduates on national political matters that the student body never authorized them to address.