Table of Contents

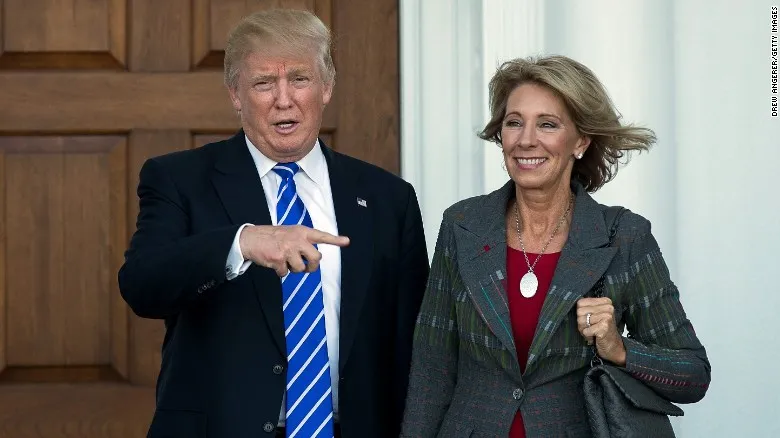

Dear Secretary DeVos:

We congratulate you on your new role as Secretary of Education, and write to you today as students to discuss an issue that plagues colleges across America.

In April 2011, Stanford students cheered when the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) imposed preponderance of the evidence — a “more likely than not” threshold — as the standard of proof for sexual assault cases tried using Title IX on college campuses. Many saw the new standard as a step forward in addressing a tragedy that affects campuses across America — one that our society has met with indifference for far too long.

At Stanford, we have seen firsthand what many students and faculty are recognizing nationally: the reforms have failed. Sexual assault investigations usually fail to secure both relief for victims and civil liberties for the accused.

Serious changes to the OCR’s Title IX guidelines are required. We respectfully request that you begin by raising the standard of proof for sexual assault cases.

Preponderance of evidence should not be the standard for sexual assault investigations. It is the lowest standard of proof in the American justice system, and is used almost exclusively to judge civil cases, not to determine individual guilt of sexual assault. And even these civil cases allow cross-examination, a right “strongly discouraged” by the OCR.

We’ve seen at Stanford how a low standard of proof hurts sexual assault victims.

A low standard of proof de-legitimizes investigations. A sexual assault survivor wrote in our publication, the Stanford Review, that the OCR’s guidelines “contribute to a greater culture of disbelief and anger at sexual assault survivors, who, as the plaintiffs, are held responsible for wrongful convictions, and seen as altogether less honest or legitimate.” The lack of stringent standards casts doubt on the impartiality of Title IX investigators and Stanford’s ability to address sexual assault effectively. In response, parties take their cases to court, prolonging the trauma for all involved.

A low standard of proof also reduces the civil rights of students accused of assault.

A letter from 28 Harvard Law School professors across the ideological spectrum stated that the OCR’s procedures “lack the most basic elements of fairness and due process” and are “overwhelmingly stacked against the accused.” While data about false rape claims are highly politicized, estimates suggest between one and eight percent of claims are false. Even at the low end of this spectrum, relying on preponderance of the evidence means that one of a hundred students who face the Title IX process will unjustly suffer serious consequences. And even if false accusations did not exist, a central tenet of a free society is that everyone deserves a fair hearing.

It’s a lose-lose for everyone involved.

At Stanford, we’ve witnessed the human costs of the 2011 letter’s expanded provisions. Title IX’s lack of protection of due process has led to lawsuits and scandals, as both parties question the outcomes of cases. One woman sued the Stanford Title IX office, claiming that a man who sexually assaulted her was not punished harshly enough. That same man, in a separate suit, claimed that the investigation deprived him of due process and that the decision was too severe.

The OCR’s guidelines letter has led to tragically mismanaged sexual assault investigations. Its lack of protection for due process has undermined their rigor. Our school has a record of losing evidence, failing to lay out a clearly defined set of rules for permissible evidence, challenging testimonies, and denying basic due process rights such as the right of the accused to view evidence against them.

There is a path forward.

Stanford has dealt with due process better than most. Working within these limitations to reform its Title IX investigation procedure last year, Stanford took the first steps towards reform by guaranteeing the accused access to lawyers and clarifying investigation procedures.

But unconstrained by the 2011 OCR letter, Stanford could do much better. Rather than imposing legally dubious standards that failed to stem the tide of sexual assault, the Department of Education should allow colleges to pioneer their own, more effective sexual assault investigation policies.

We could imagine a burden of proof proportional to the punishment: low evidence could result in the victim or accused being moved to a different residence hall, while clear and convincing evidence could trigger expulsion. Individually tailored policies would serve justice while still protecting due process so long as Title IX’s other requirements remain in place.

Sexual assault is a crime that attempts to rob victims of their dignity. This grave tragedy must be addressed by a legitimate process that restores this dignity. For the past six years, universities have mishandled case after case of sexual assault. They have failed to secure justice for survivors, and have violated the civil rights of those accused of assault. Unless you raise the standard of proof and consider other reforms, what should be tragic anomalies of misapplied justice will continue to be the norm.

Sincerely,

The Editorial Board of The Stanford Review