Table of Contents

Joshua Rauh is the Ormond Family Professor of Finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, the George P. Shultz Senior Fellow in Economics at the Hoover Institution, and a Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Rauh has established himself as a leading voice on tax policy, pension economics, and fiscal sustainability, having advised policymakers as the Principal Chief Economist for the Council of Economic Advisers in 2019-2020. He earned his Ph.D. in economics from MIT in 2004 and joined Stanford’s faculty in 2012.

This conversation follows Professor Rauh as he cuts through the fog surrounding America's most consequential fiscal questions. From California's proposed wealth tax to the hidden mechanics of pension accounting to the mathematics of federal debt, Rauh demonstrates how discerning analysis can reveal what political narratives obscure.

The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

Jack Murawczyk: Your research spans tax policy, pension economics, and energy finance – all domains where complexity and political incentives obscure fundamental truths. What is it that attracts you to these subjects? Where does your truth-seeking impulse come from?

Joshua Rauh: When I started studying economics seriously in graduate school, my interests coalesced around the use and abuse of economics in policy, particularly where the narrative drifted far from economic reality.

The more I learned, the more I saw examples where economic reasoning was being applied in ways that ran counter to basic integrity. Government policy based on economic fallacies that sound good doesn’t serve the people. That’s the unifying theme behind tax policy, pension economics, and energy finance. In tax policy, the main fallacy is clinging to the idea that behavioral responses won’t be significant, that you can tax people to a large extent and they won’t change their behavior much. The assumption is you’ll still bring in just as much revenue as you would have otherwise.

Pension funds manage trillions of dollars in assets to fund promised retirement benefits for public employees. The money set aside turns out to be inadequate. They’re using a budgeting model that flies in the face of financial reality. They treat the equity risk premium as if it weren’t really a risk premium, assuming they’ll achieve their 7% or 8% returns with absolute certainty.

In energy policy, there’s a lack of thinking about trade-offs. Investing heavily in renewable energy means trading off affordability and reliability. Pretending those trade-offs aren’t there isn’t productive and won’t serve people well.

Through studying economics and following policy, I kept seeing this tension between what economic logic actually says and what politicians say and do for gain – a kind of demagoguery, hype-economics that fundamentally isn’t valid. These institutions claim moral authority while shifting costs onto others in hidden ways.

That’s been a motivating concept for me for a long time.

JM: Your research has tracked how high-income taxpayers respond to state tax changes. What does it suggest about the durability of Silicon Valley’s tax base, in light of the recent proposition of a one-time tax of 5% on the total wealth of California billionaires? Is California at risk of a “fiscal death spiral,” or is it immune due to talent and climate?

JR: California is nowhere near immune to this. This is a potential major disaster for California.

We’re running the risk of experiencing what happened to Detroit after the 1950s and 1960s. We assume that because the weather’s nice, things will be fine. But these systems are far more fragile than people think.

Let’s look at the billionaire wealth tax proposal. Since it was announced in late 2025, there has been a scramble of high-net-worth individuals leaving California. If this ballot proposition passes in November, then January 1, 2026, becomes an important date for establishing residency. A number of people said, “We’re not sure we want to stick around for that.”

The architects of this ballot proposition projected $100 billion of income to the state from this tax if it passes. Losing just Sergey Brin and Larry Page wipes $25 billion – a quarter of the projected revenue – off the table immediately. It does drive people out of the state.

Another factor that’s often underestimated is what happens to the entrepreneurs who stay. What about their future business decisions? High-net-worth individuals have many choices for what to do with their money. One thing they can choose to do is invest in new businesses here in California. When you have top marginal tax rates as high as they are right now, you think twice before doing more business investment in California.

What do you do if you know that as soon as your wealth crosses a billion dollars, 5% of it will be taken away? Many people in the public seem to vilify the founders of these companies because of their wealth. But if you just look at the number of jobs these companies create for California, this is a disaster. Elon Musk is perhaps the best example: SpaceX, Tesla, then buying X.

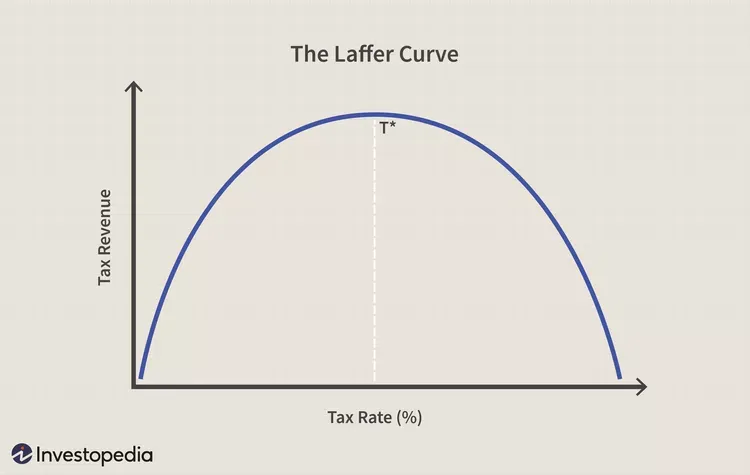

The Laffer curve is absolutely true, and California has reached that point. What’s even worse is how much prosperity you’re destroying in the process. Imagine a proposal that would bring in one extra dollar to the government’s coffers but would destroy a thousand jobs. Bureaucrats sitting in Sacramento would say this is a great policy: we’re getting extra dollar revenue! But when you measure the deadweight loss from taxation, you’re destroying prosperity, you’re destroying well-being.

JM: Where do you most sharply disagree with the consensus view on American public economics? Where do you see the policymakers or public getting something fundamentally wrong?

JR: The first place they’re getting things wrong is how we view tax policy. We’re viewing it too much from the lens of “how do we bring an additional dollar into the government’s revenue” versus balancing that against what actually happens to prosperity in the economy.

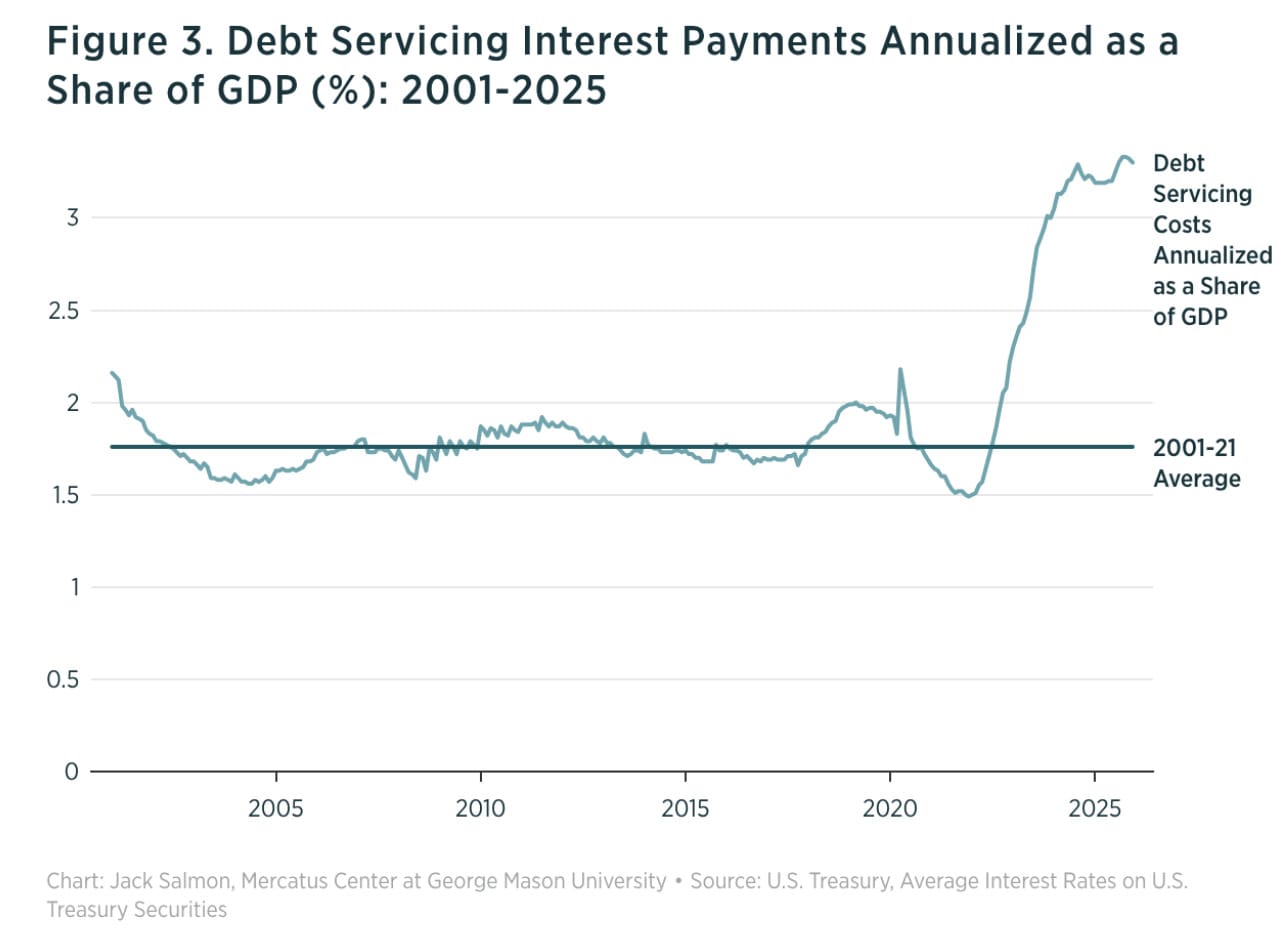

The other place is the danger of federal debt. People talk about it in abstract terms, yet we’re not doing anything about it. It’s amazing to think back on the fact that by the year 2000, we had a surplus. In 2025, we’ve got $38 trillion of debt, and we’re running $2 trillion deficits every year.

Look at how much of our revenue is going straight out the door to pay interest on our debt. Over twenty cents of every dollar you pay the federal government in taxes goes straight out the door to pay interest. That number is rising and scheduled to continue under the current policy.

And it’s fragile in the sense that if the interest rates we pay on government debt are just one percentage point higher, borrowing costs would increase dramatically.

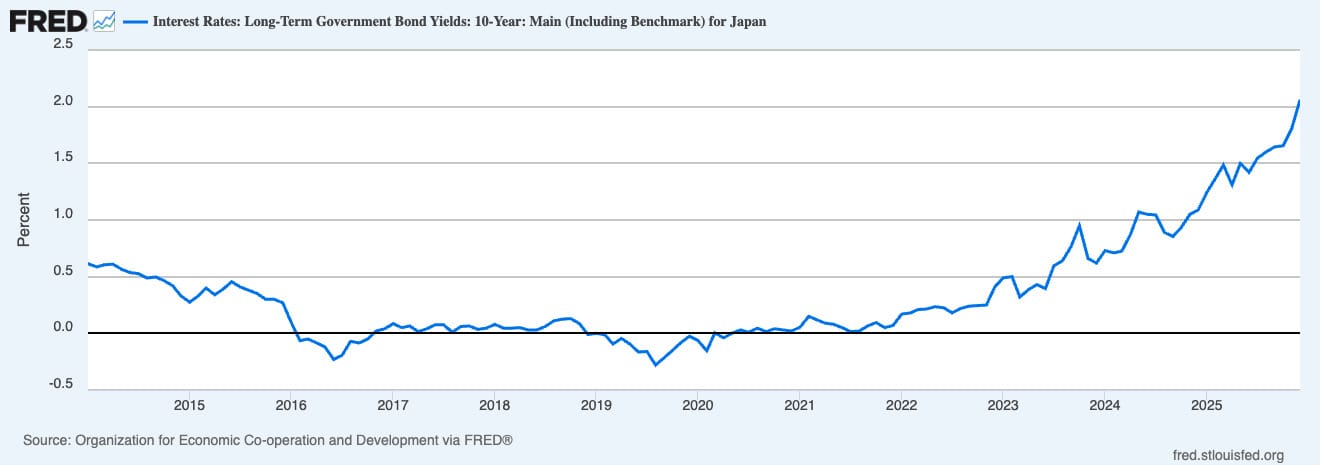

JM: Just look at the Japanese 10-Year today!

JR: Exactly – borrowing costs increased dramatically, putting incredible strain on government finances. There’s still too much complacency. If you look at every financial crisis in history, these spreads were always thin until they weren’t. A week before the Greek financial crisis blew up in 2009, Greece had razor-thin spreads to German bonds. Then people realized.

There are institutional reasons people have wanted to hold Treasury bonds. That takes a while to unwind, but it is unwinding. I’m very concerned about a U.S. fiscal crisis.

We’re spending so much more money than we’re taking in from taxes, and doing it through these welfare programs, while the world’s not getting any safer. We haven’t had to fight an existential war in a very long time. We’re not putting ourselves in a robust position to fight such a war if we're already running massive deficits during peacetime.

My level of concern exceeds the economic orthodoxy right now. Shouldn’t it be news when the percentage of federal revenue that goes out the door to pay interest crosses 24%? That should be front-page news.

JM: How do we solve this? Are we too far gone?

JR: I don’t think we’re too far gone. I also don’t think there’s going to be some deus ex machina. The only way is through sustained pressure on our politicians to make this the number one priority. That’s the answer for readers: these are the long-term challenges that matter, that should be keeping you awake at night. It’s a multi-decade undertaking.

You don’t like the fact that mortgage rates were 2.5% in 2020 but are now 6.5%? You think that’s bad? Just wait. Look back at the 1970s…that’s what we’re hitting.

JM: My grandparents say their mortgage rate was in the mid-teens!

You served as Principal Chief Economist for the President’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) in 2019 and 2020. I’m curious about your experience there and the differences between the purported Ivory Tower and the White House. Is there a fundamental disconnect between the academic models we study at Stanford and the way policy is crafted in DC?

JR: It was a great honor to be there, and there are real distinctions. People with academic training who spend time in Washington quickly learn (and this is a bipartisan statement) that the best thing you can do is try to stop bad policies and correct false narratives.

From that perspective, contributing to that effort was exciting. One of the big ones was examining how the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was playing out in the economy. By 2019, the receipts were starting to come in: lower parts of the income distribution were performing significantly better. That was an exciting time to be there. I was applying the frameworks and tools I’d developed throughout my career in a policy setting.

Where there was a real conflict was with government bailouts. Bailouts often claim they’re helping one group of people, like employees. If we think about the airline bailouts during COVID, they said they were bailing out the employees, but actually, they were bailing out investors in the company and creditors.

JM: As was the case with SVB.

JR: That was another one of these fiscal or institutional illusions where you’re pretending to benefit one group of people, but through the complexity and the way financial markets work, you’re benefiting a totally different group. Bailouts are the ultimate regressive policy.

Before I even went to Washington, I made a contract with myself: if there was ever going to be a massive bailout of the economy, the way there had been in the global financial crisis, I was not going to sit around to be part of that. What happened in early March 2020 was that we had the mother lode of all bailouts approaching. I left before the CARES Act because I didn’t want to be associated with that.

My line in the sand got crossed while I was there, and I made the choice that I preferred to be commenting on and analyzing the situation from the outside.

JM: You’ve researched and written extensively on underfunded pensions and how public pensions use and abuse discount rates to hide the true size of their liabilities. The consensus says public pensions can underwrite a 7% return in perpetuum. What are the consequences when accounting can no longer obscure reality?

JR: The consequences are that you end up with a crowding out of public services. People are bearing a higher tax burden than they ever had before, and yet the quality of public services they receive is getting worse.

Why is this important? If you underestimate how much money you need to set aside to prepare to pay these pensions, then every year you’re going to have to put more and more in, and it’s going to crowd out the rest of the budget. That crowding out is felt by anybody who relies on public services: education, public safety, and infrastructure. In every instance, you fall more and more behind. More and more money is going every year into pension funds, and taxpayers just see fewer and fewer services.

JM: Which essentially forces pension funds into riskier, illiquid assets; it seems like they’re being pushed further up the efficient frontier just to meet their returns.

JR: That’s exactly what’s happened over the last 15 years. Pension funds looked at university endowments and said, “You guys are investing in private illiquid assets. Looks like you’re doing well. Maybe we can do the same.”

That’s a problem because if you study the illiquid asset classes, it’s important to be top quartile because there’s extreme return dispersion. The asset allocators at these state pension funds knew this, but did it anyway because it allowed them to justify their return assumptions. They could keep saying, “We’re still going to get 7% because the Yale University Investments Office got 7%.” Yet they do not have access to the same fund opportunities. That’s the fundamental misconception.

JM: You launched a new course this quarter: Energy Finance. Why and why now?

JR: A few years ago, I started looking at how a number of pension funds around the country were investing in infrastructure assets. I did a project with a colleague where I looked at the ownership structure of every power plant in the United States.

What struck me was how the renewable energy buildout had been financed by private equity. People lazily associate private equity with the oil and gas industry. There’s a narrative accusing private equity of keeping the coal economy alive. But there’s no evidence of that in the data. Private equity did not do a lot of buying of coal plants.

Secondly, I realized people were not being forthright about what the trade-offs are in terms of the big shift to renewables, or even being honest about how much progress is being made and can conceivably be made. I saw sloppy narratives I wanted to correct.

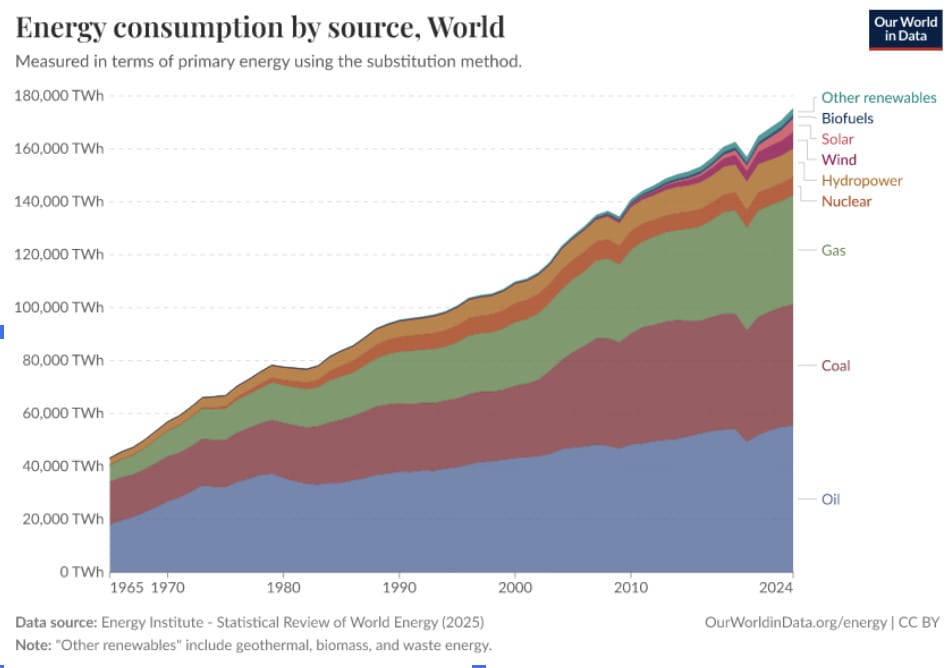

There’s a great essay called Halfway Between Kyoto and 2050 by Vaclav Smil. If you look back at the time of the Kyoto Accords in 1997, 86% of energy consumption in the world was from fossil fuels. Two decades and trillions of dollars later, that number is at 82%.

If people are concerned about CO2 emissions, we’re emitting far more than ever before, and we have not seen a climate impact to the degree we’re projecting. There were questionable narratives, sloppy thinking, and a lack of willingness to see that there are trade-offs here. It’s not black and white.

So the class came from my desire to look at the energy sector from a pure business perspective. We have 92 students in our class, and I’ve been delighted with the response.

JM: What are you trying to impart to the next generation as you teach college students at Stanford?

JR: There’s a classic statement by Milton Friedman: “One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.” The intentions can be good, but you have to judge on the basis of results.

Also, relentlessly question. I try to get up every day and question whether everything I thought I knew yesterday is right or wrong. Always be aware that there are trade-offs for anything you hear about government policy. I want students to come away with that thinking.

JM: We’ve covered a lot of challenging and interesting intellectual terrain. Beyond the interest rates and policy briefs, where do you find magic and meaning in the world?

JR: Magic and meaning is having the opportunity to mentor young economists and people who are just interested in learning. People sometimes ask me, “Who are your favorite people to work with at the GSB or at Hoover?” I have great colleagues at both places, but the first thing that pops into my mind are my pre-docs and postdocs. Part of that has to do with some of my own mentors. You always try to give it back to the next generation.

Outside of work, I play three instruments badly (violin, piano, guitar) and that’s always been fun. It’s funny, in work I have this philosophy that anything worth doing is worth doing well. I don't believe that in music, because otherwise I’d go crazy.

Recently, in the last few years, I took up another hobby that’s delivered a few magical moments, and that’s windsurfing. The first time I got my own board and my own rig and put the whole thing together myself, and finally, after fiddling with everything for hours, got it up and going, just that first hour sailing around the lake, that was a magical feeling.

JM: The triumph of individualism.

JR: You hit on something. All my hobbies tend to be individual. I mean, I’m a professor after all. But that was definitely a magical feeling.

JM: What’s the one chart or data source you check every morning that cuts through the noise?

JR: Everybody should be looking at where the 10-year Treasury yield is. It’s going to ultimately matter more to your life than the stock market, because you’ll want to buy a house.

JM: What books most shaped your thinking?

JR: This Time is Different by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff is a terrific history of financial crises written in 2009. At that time, the final chapter was about state and local government distress. But if we apply that framework to where we are now, the big final chapter would be the fear of a U.S. fiscal crisis.

My second recommendation is The High Cost of Good Intentions by my colleague John Cogan. It's built on Milton Friedman's idea that you have to judge policies by their outcomes and results, not by their intent. It's a history of entitlement programs in the United States, going all the way back to pensions for Revolutionary War and Civil War veterans. Those are the two great economics books that affected my thinking.

JM: To conclude, what’s the kindest thing someone has done for you?

JR: There is a teaching mentor I had in grad school. I think about this person every time I set foot in an MBA classroom. His name was Kevin Rock.

I didn’t have a great financial package at MIT Economics. During my second year, I needed an additional teaching assistantship to fill in my financial aid. I saw that Kevin Rock had made a posting for being a TA for his MBA corporate finance course, so I sent him a note of interest, and he interviewed me.

Kevin Rock had gotten a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and had written some famous papers with Merton Miller on IPO underpricing – the problem of first-day pop, why it persists. This was like 40 years ago and it still persists today…

JM: Much to the chagrin of Bill Gurley!

JR: I remember the interview with him, and it was clear to both of us that I was not qualified to be a TA for MBA corporate finance. I actually should have had to take the class! For some reason, maybe he thought I had some potential, he hired me.

Every time I set foot in an MBA classroom, I think of him. Wow, it is really great that he gave me that opportunity.