Table of Contents

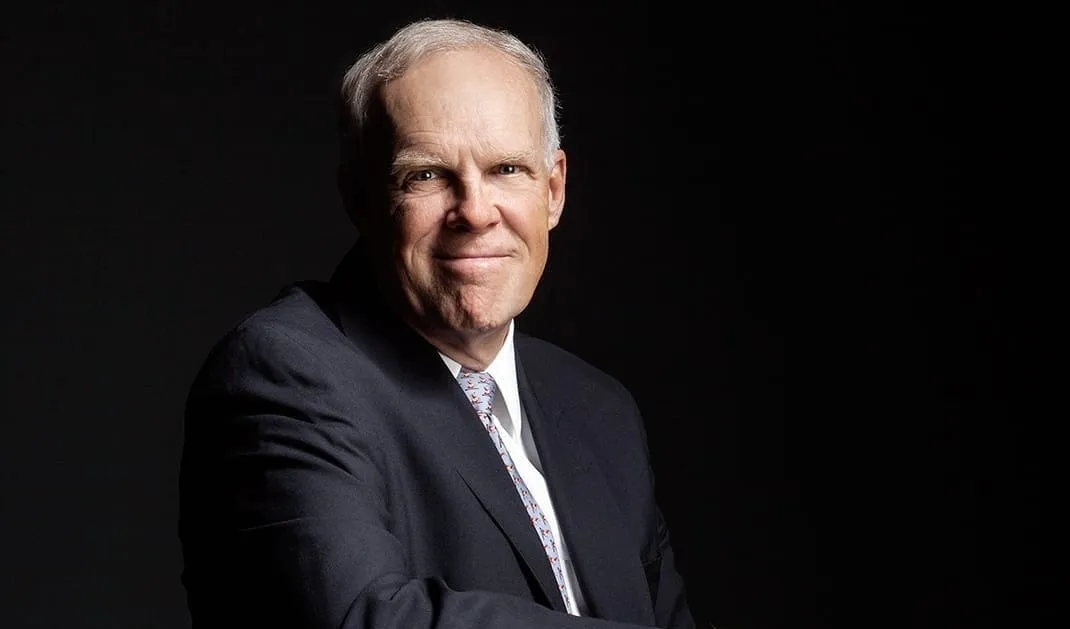

John L. Hennessy is President Emeritus of Stanford University as well as the James F. and Mary Lynn Gibbons Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering. He served as Stanford’s 10th president from 2000 to 2016. During his presidency, he launched Knight‑Hennessy Scholars, the world’s largest fully endowed graduate fellowship program, and became its inaugural Shriram Family Director in 2016.

A pioneer in computer architecture, Hennessy co-founded both MIPS Technologies and Atheros Communications, helping to commercialize Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) technologies that reshaped modern computing.

Currently, he serves as Chairman of the Board of Alphabet Inc. and sits on the Board of the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation.

The conversation below explores a wide range of topics: from the transformation of higher education to the evolving semiconductor landscape, US-China geopolitical competition, and more.

Abhi Desai: Thank you so much for doing this, Professor Hennessy. We really appreciate it.

Starting off, you've now led two institutions at the heart of global innovation, Stanford and Alphabet. In the US-China technology rivalry, we see two contrasting models emerging, one built on coordinated national strategy, another on decentralized entrepreneurship. From your experience, which model produces enduring innovation, and what institutional features make that possible?

John Hennessy: I should say, first of all, that I'm the Chair of the Board of Alphabet, but the management team really leads the company. I just help and hopefully provide some useful input.

It would come as no surprise that I favor the US approach, but let me raise a note of caution here, which is that I worry the country's reduction in funding for research is going to undermine our lead. At a time when China is increasing its investment in STEM technology and other critical areas, the US is cutting its investment; that will undermine the long-term innovation space, and I think that's the real danger for the United States in a competition with China.

AD: How has the role of the university president changed since your tenure? Obviously, it was a tenuous role across the nation.

JH: As you know, we had bumps in the road. During the time that I was president, we had the 2008-2009 financial crisis, but the combination of the pandemic, followed by the situation around Gaza, followed by the uncertainty over federal financing and federal commitment to universities, has made it much more difficult than it ever was during my time, and added a lot of uncertainty that has been hard to resolve.

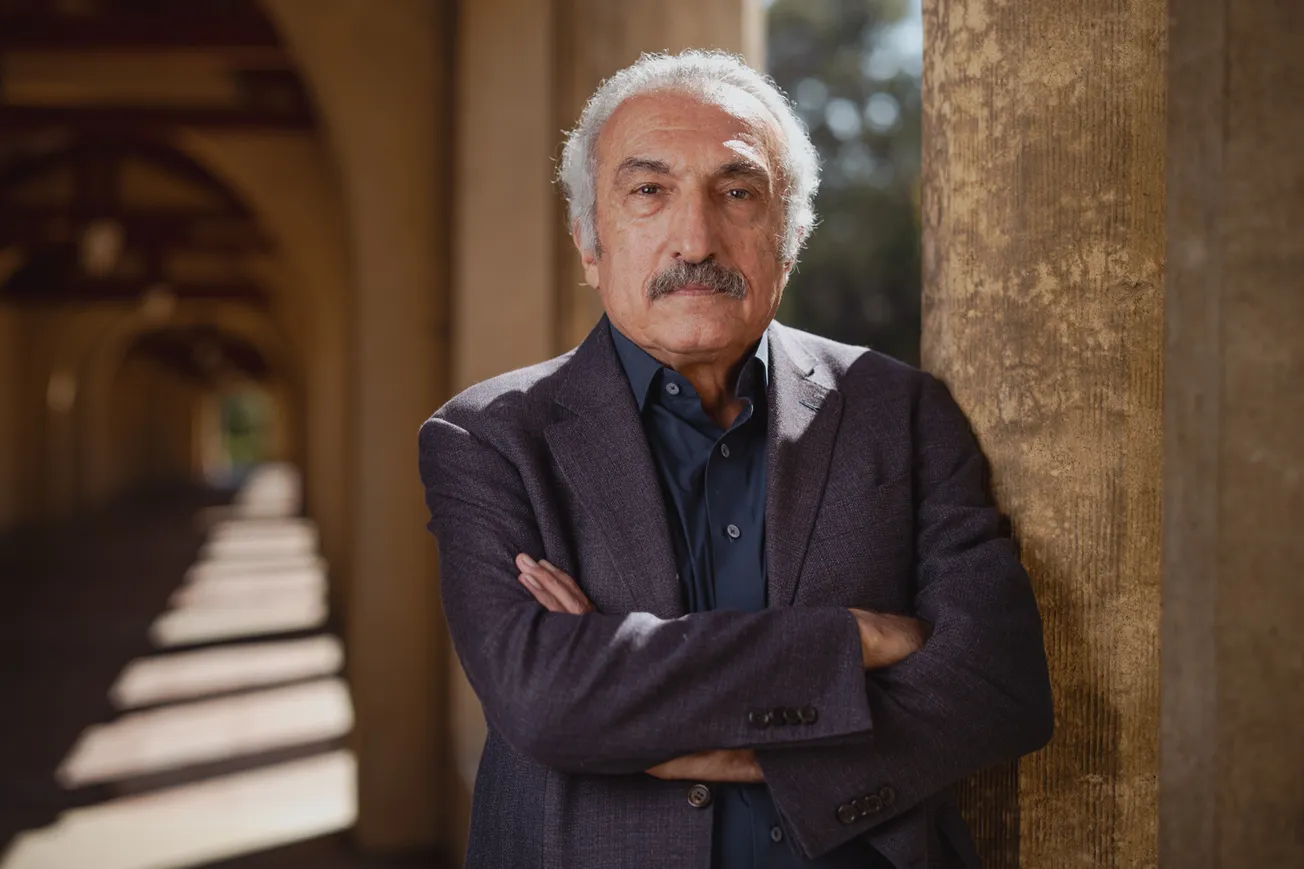

AD: Stanford Economics Professor Nick Bloom has a paper called “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find”, which argues that research productivity per scientist has collapsed even as total research and development spending soars. Do you agree that innovation has slowed? If so, what can universities do to restore the velocity of breakthrough research?

JH: I think it's slowed in some fields, not in others. It's perhaps been more difficult in some fields to find those kinds of breakthroughs, although just when you think it's getting difficult, you create things like CRISPR, which creates a lot of innovation around the biotech space at a time when it was moving slowly otherwise. I think that the new tool with respect to research is going to be AI, and I think AI will enable us to speed up the scientific discovery cycle, thereby resulting in a return to greater productivity than we've seen in the past.

AD: On AI, you spent your career building the bridge between academia and industry, from MIPS to Alphabet. Has that bridge gotten stronger? Or are we reaching a point where cutting-edge innovation, especially in AI and semiconductors, can no longer happen inside our universities?

Many AI leaders, from Professor Fei Fei Li to Professor Percy Liang, have warned that academia is, quote, “falling off a cliff” in terms of compute access, with hundreds of GPUs versus industry’s many hundreds of thousands. Can we still contribute to frontier research in AI?

JH: It's a very good question. There's certainly plenty of work to be done and enough space. I absolutely agree with the point that Professor Li made, namely, we are falling behind in terms of access to high-end compute. That will limit the work we can do; some of it is perhaps not critical. We don't have to build the giant foundational LLMs, for example. But in other areas, it will be really crucial to get that access. And I think the work that Fei Fei Li and others have done to try to advocate for a significant federal investment is crucial if we're going to keep up.

AD: You've long been a champion of international collaboration. Given today's geopolitical climate, particularly with changes to various visa programs, what do you think is the enduring importance of global talent to American universities, and how can they balance openness with legitimate national security concerns?

JH: There are legitimate national security concerns. The view that we've had for many years is that this is the domain where the federal government is best positioned to determine whether or not there is a danger in letting somebody in the country. Certainly, the method we prefer is that we want the best and brightest to come to the US.

You just have to walk through the companies in Silicon Valley and see how many people have come from outside, and now you have some of the biggest companies in the world, Alphabet, Nvidia, led by people who immigrated to the US, initially as students. That's an important reminder of the talent magnet that the US has been, and keeping that talent magnet is critical if we want to continue to be world leaders. At the same time, we do have to pay attention to the national security issues. That's where we need to be in a partnership with the federal government.

AD: How should students prepare for the rise of strong AI? Many students are still not reasonably thinking through this in terms of systems that can automate much of the work that they hope to do during their career, despite the fact that these systems can already do many of their problem sets! Have your interactions with Stanford faculty, as well as with Google DeepMind, informed your views on this?

JH: The rate of progress is simply stunning. AI is moving faster than any technology has ever moved in my lifetime, which includes the microprocessor, the personal computer, the World Wide Web, and the internet. All those technologies moved fast–this is moving faster. First of all, students are going to have to become familiar with AI as a tool, because it will be a tool that's used in a highly universal manner. So that's the first critical thing.

The second is to develop skills for which you, as an individual, or a company with AI tools, are better than the AI tool working by itself or by the individual working by itself. There are some good examples of this that have come up from studies, such as a medical diagnosis, where a physician plus an AI assistant is better than either the physician or the AI assistant working alone.

There are lots of examples of that, certainly in coding as well. One would be careless if one assumed that code currently produced, at least by some AI system, is without flaws every time. There's a continuing role for human intelligence and diligence, which will be critical.

AD: Alums I've spoken with have expressed concerns that the value of the Stanford degree has declined dramatically in terms of intellectual quality. Are you concerned about this possibility?

JH: No, I don't think the value of the degree has declined in terms of intellectual capability or what the students are learning. I favor a broad education that exposes students to lots of different opinions, ones they agree with and ones they perhaps don't agree with, as part of their education. Certainly, the quality of students has improved over many years, and many of those alumni who were admitted 30 or 40, or 50 years ago would not get in today.

AD: Expectations for students to engage with the humanities have dramatically decreased, even over the last 20 years. Should this change, particularly in a world where AI poses a threat to STEM degrees? Do you think this should be a larger part of the Sanford education, especially on the undergraduate level?

JH: Certainly, we would like to see more students at the undergraduate level pursuing degrees in the humanities and some of the social sciences that have also fallen off over time. I think that would be healthy. Stanford has always allowed students to pick their own major, and will continue to do so. Figuring out how you make it more attractive to think about majoring in a broader set of things, particularly as we expand the undergraduate population, is important.

AD: The million-dollar question: Should students still major in computer science? Do you expect the number of students studying the subject to decrease?

JH: Maybe we've reached the peak, and there'll be an asymptote, if not an actual decrease. Certainly, I think computer science will still be important. We're a long way from replacing all human functions. We're a long way from an AGI system that operates at the human expert level for really hard problems.

I think there'll be an ongoing role. Computing, in a very broad way, has become this foundational discipline that touches virtually every other discipline. In the same way that other key things you learn are critical, I think that's the way computer science will be. Some of those students should be majors, and some should think about other alternative uses of the technology in the context of what their other interests are.

AD: Moving on to the Knight-Hennessy program, how do you feel that the program has evolved over the last decade, as the first cohort of scholars start to make their mark in the world? Have you seen any trends in what scholars are hoping to focus their energy on, whether it be public service, entrepreneurship, or something else?

JH: Certainly, there is an entrepreneurship buzz among our scholars, as there is on campus in general—starting an AI company of some sort these days, or some biotech as well. I think some of our scholars have been disappointed in their ability to pursue public service work, given the uncertainty. For example, we had one scholar whose dream job was at USAID, and it disappeared, so we see some uncertainty clearly in this.

There's some scholars who are interested in working on issues around climate change and environmental sustainability, and they've seen less traction in that area than they expected, say, three or four years ago. So there's some concern about that. But I think on balance, the scholars are going on to do useful things.

I think in terms of the program, some of the things that we envisioned from the beginning continue to be the backbone of the program–bringing together really smart people from a wide range of disciplines to interact and learn from one another is still core to what we try and do, and still one of the most rewarding parts of the program.

AD: Stanford President David Starr Jordan said in 1904 that “The college of the West is home to no dewy-eyed monk, no stoop-shouldered grammarian”, the true Stanford scholar, he argued, “would be the leader of enterprise and the builder of states.” Do our students still live up to this? And do you think we still attract a different pool of students compared to our eastern counterparts?

JH: Each institution is unique in terms of the students it attracts. Stanford, if you look at the breadth of our student population, I'd be hard-pressed to find an institution that has the same breadth. You know, Harvard's got a lot of depth in some areas. MIT's got a lot of depth in some areas. Together, MIT and Harvard would model Stanford.

AD: Obviously, you have a long history in the semiconductor industry between MIPS and Atheros, and RISC as well. Looking at the CHIPS Act and US export controls, do you think these are the right levers to ensure long-term US leadership in semiconductors?

JH: I think the CHIPS Act was a step in the right direction. I worry about parts of the long-term investment around Natcast now being canceled. How do we maintain that industry in the long term?

The right thing to realize about semiconductors is that it's not just about computers; it's about everything. It's a foundational technology. During the pandemic, when it was hard to get access to semiconductor supply, the car industry collapsed, because you can’t build cars without being able to get semiconductors these days.

So it's a fundamental technology, and that's why the US needs to ensure that it has a supply and that we push the technology as fast as it can go. It'll be a challenge for the United States to get its leadership position back. I think there are steps in the right direction. Export controls are good as a short-term measure to deal with some issues. They're not good in the long term because they encourage other people to innovate, who eventually will try to close the gap with the US. In the short term, they may make sense, though.

AD: Related to this, do you think that America can rebuild its capacity for large-scale industrial innovation, particularly in semiconductors?

JH: I think there's at least a shot to do it with the CHIPS Act, with the focus on it and the critical understanding of how important it is to do. But that doesn't guarantee success. You need to reset your mindset and realize, for example, that a fab runs 24/7 and you have engineers on staff 24/7. Well, in America, engineers are not used to working in the dead of night.

There was a time when they were, during the Sputnik era and during the 50s. My father was an engineer, and he worked night shifts because there was so much demand then to catch up on. Whether or not the US can shift into this mindset that happens in other countries is the question. It happens in Taiwan, it happens in South Korea, it happens in other countries. It's a mindset shift for the US if we really want to be leaders in these technologies.

AD: As Alphabet grows from a search-powered business to one that has a variety of different arms across Waymo and YouTube, and even sells TPUs now with the recent Anthropic deal, what excites you most about the company, and as it relates to the future, what technologies are you most excited by in the long term?

JH: Any company that wants to survive in the long term has to differentiate its product line and has to get into other fields over time. That's a goal from the time we changed the name of the company from Google to Alphabet–to really try to branch out into related businesses.

That's been a key goal. The AI revolution is just so incredible. If you look at the transformer paper, it's now eight or nine years old. It completely changed the field. So that kind of innovation, that kind of leap forward, is really exciting to see, and what I think every American company that wants to thrive over decades needs to be able to do.

AD: China has tried to replicate Stanford's model through initiatives like Zhejiang University. They call it a ‘Chinese Stanford’, which has produced researchers behind systems like DeepSeek. Given that context, how should US academia think about open collaboration versus more protectionist policies, even in research?

JH: It's really difficult to figure out how you navigate the situation so that you can collaborate. There are certainly areas that are far enough away from commercialization that collaboration is easier. There are areas that are much closer to commercialization, where collaboration will be difficult.

AD: Having been in Silicon Valley for some time, what would you say are the biggest similarities to prior technological explosions, like the dot-com boom, and the biggest differences now with AI, especially as it relates to things on campus and students?

JH: I think AI is going to be transformative. You know, the question on lots of people's minds is, are we in a bubble? We may be in a bubble.

We're not in a bubble in terms of what the technology can do, but we may be in a bubble with respect to valuations, particularly of private companies, some of which have yet to develop a business model that gains traction.

There's a lot of debate over that, and appropriately so. We kind of guessed we were in a bubble when the dot-com explosion occurred twenty-five years ago. Yet the industry was unable to avoid it, and it filtered through the entire industry. There was a quick recovery because once some of the failed companies were cleared out of the way, the companies that really had successful business models could forge ahead, and we may see the same thing again.

AD: I was recently reading a 1983 essay on Intel titled “The Tinkerings of Bob Noyce: How the Sun Rose on Silicon Valley.” The culture described then, of freedom, of young people taking bold risks and defining the future, seems to be stifled now. Is this because the populace as a whole has aged? Certainly, it feels as though technology has less of a cowboy attitude compared to what it once did, and even at Stanford, a culture of safetyism seems to have set in, surrounding things like drinking policies. Is this something that we should fight against?

JH: Oh, it's a good question. When the Valley was young, it was a very different environment. Venture capital was relatively hard to come by. There were not many startups, and even through the 1980s, it was a very different environment than it is today. Namely, in those days, the success rate for Stanford spin-offs was quite high, much higher than it is today. The industry was very different–they were focused on boosting their success rate, and the success rate was probably two to three times what it is today. Now, they perhaps weren't companies at the same scale as were built in the 90s and on, but they had a much higher success rate.

Today, the focus seems to be on going after the one grand slam, home run, hit–the next Google, Meta, OpenAI, whatever. That's a different mentality. I'm not saying it's better or worse, but it's different. Of course, the Valley's grown up a lot, and there are a lot more investors, there are a lot more startups, and that's certainly changed things from an earlier time, but technology has changed as well, and clearly, right now, we're in this shift to AI as the dominant technology.

If anything, semiconductors are in the late stages of their lives in terms of progress compared to the rate they once had. The thing about the Valley is that waves of innovation have been the driving force for the last 50 years. Early on, this is the semiconductor and the invention of DRAM, and then the microprocessor, and then the internet, then the World Wide Web, then mobile.

These waves of innovation have come along, and each of these waves creates new companies. Some of the old companies survive and thrive, while some of them don't, and new companies get created. There's this creative destruction process that goes on all the time, but that's part of the renewal process, and is one of the things that has made the Valley better in the long term.

AD: Universities exist to produce new knowledge and open minds. In an era where AI models can generate vast amounts of knowledge autonomously, what remains uniquely human and uniquely academic about discovery?

JH: That's an interesting question, in the sense that what will AI do well when it comes to the creation of new knowledge, right? Obviously, AI is already very good at analyzing existing knowledge, presenting it in new ways, and helping people understand it. It's really made a lot of progress in that. I think the more interesting question is, how will AI help advance research and advance the exploration of new ideas? I think the role of humans and AI could be complementary in that hypotheses can still be primarily the domain of humans, while trying to accelerate the ability to explore those hypotheses is something that AI could do very usefully for us.

AD: Has the nature of curiosity changed in the digital age? Are students more entrepreneurial today, but less fundamental in their intellectual curiosity, compared to previous generations?

JH: We find ourselves right now in a bit of an entrepreneurial fever, shall we say, where everybody wants to start a company. When I talk to students, they say, “Oh, I want to start a company.” I say, “Well, tell me about your technology or your invention,” and they say, “Well, I don't have it yet, but I want to start a company.”

Great companies are built around two things. They're built around technology breakthroughs, and what I would call a broad class of business model breakthroughs. Amazon is a business model breakthrough; at least initially, it wasn't a technology-deep company. It was sell everything on the internet, make that work. This is not hard computer science technology; they have become a major technology company, but they weren't at the beginning.

Google was a technology company from the beginning, right? Google's search algorithm was better than other search algorithms. So those are the two models that build lasting companies that can be transformative. Trying to think methodically about how to go after a space and really make a difference, and make it sustainable. Great companies are not one product. They're an ongoing creation of products. And I think that's important in the long term.

AD: In a prescient 2003 article entitled “The True Test of Free Speech,” you anticipated many of the threats that free speech would face on campus in the coming decades. After a tumultuous period, Stanford is beginning to see a broadening of perspectives. As far as we are aware, there are multiple right-wing political clubs that have emerged on campus. What do you think about the current state of free speech at Stanford? Is the university moving in the right direction?

JH: I think we're certainly, as you alluded to, moving in a better direction. Some of the cancellation viewpoints, which took hold in an earlier era, even self-cancellation, because we saw in surveys that many students held back their opinions if they didn't agree with the conventional wisdom or the more popular viewpoint. I think we've seen that abate, and that's a good thing for having those discussions. I think we're moving in the right direction, and are making it clear that the job at the university is not to take a point, not to take public stands on all kinds of issues that are secondary, not directly germane to the health of the university. I think that was a good step, and reinforcing that view was critical.

AD: What was the biggest mistake the university made with regard to free speech in the last, say, 20 years?

JH: That's a good question. I think the biggest mistake we made was not adequately preparing our students to engage in civil debate and to disagree with each other in a fashion that wasn't disagreeable. I think we simply did not do a good enough job preparing students. And I think this, by the way, applies to many universities.

AD: On a lighter note, the Review recently published an article calling for the return of Lake Lagunita. Many alumni remember when Lake Lagunita actually held water. If you could restore one piece of old Stanford, whether symbolic, like the lake, or institutional, like a tradition, what would it be?

JH: I would restore the PAC-12. I would restore athletics to something focused on the quality of the experience for student athletes and for our alumni and students.

AD: Great answer. Last, a lightning round–what was the most formative class you ever taught or took?

JH: Taught or took? Well, I'd say the most formative class I ever took was probably my first programming course. In terms of teaching, probably teaching the computer architecture sequence, which led to writing our books with Dave Patterson, was really formative. If I hadn't been teaching the course, I wouldn't have written the book.

AD: If you could start a new department at Stanford today, what would it study?

JH: I actually wouldn't start one department. What I would try to do is build up the computational capability in a whole variety of departments, from the social sciences and humanities to, of course, the STEM disciplines, but the STEM disciplines, I worry about less, because it's very natural for them. But I think this technology is going to change the way we do lots of things in lots of fields.

AD: What's your favorite place on campus for reflection or inspiration?

JH: Oh, probably the mausoleum. That little section of campus is a wonderful place to go.

AD: What do you think your biggest success was while running Stanford?

JH: Really enhancing financial aid for graduate students and undergraduates.

AD: Andy Grove famously quipped that “only the paranoid survive.” What are you most worried about for Stanford?

JH: I'm worried that the traditional partnership between the federal government as a funder of research and universities as undertakers of research is breaking down.

AD: What's one prediction you have for Stanford in 50 years?

JH: That it will still be here.

AD: Thank you so much, Professor Hennessy.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity, length, and grammar.