Table of Contents

On November 5th, The Center for Russia, East European and Eurasian Studies hosted a lecture by former Ambassador to Pakistan and Poland Thomas W. Simons. Simons is a former Stanford professor and current lecturer at Harvard University.

At the beginning of his lecture, “Russia, It’s Neighbors and the U.S. since 1991,” Simons observed that most news today concerning Russia is negative. Russia is opposing sanctions on nuclear weapons, monopolizing gas transit in Eastern Europe, and attempting to establish a Soviet-era sphere of influence over its neighbors, he said.

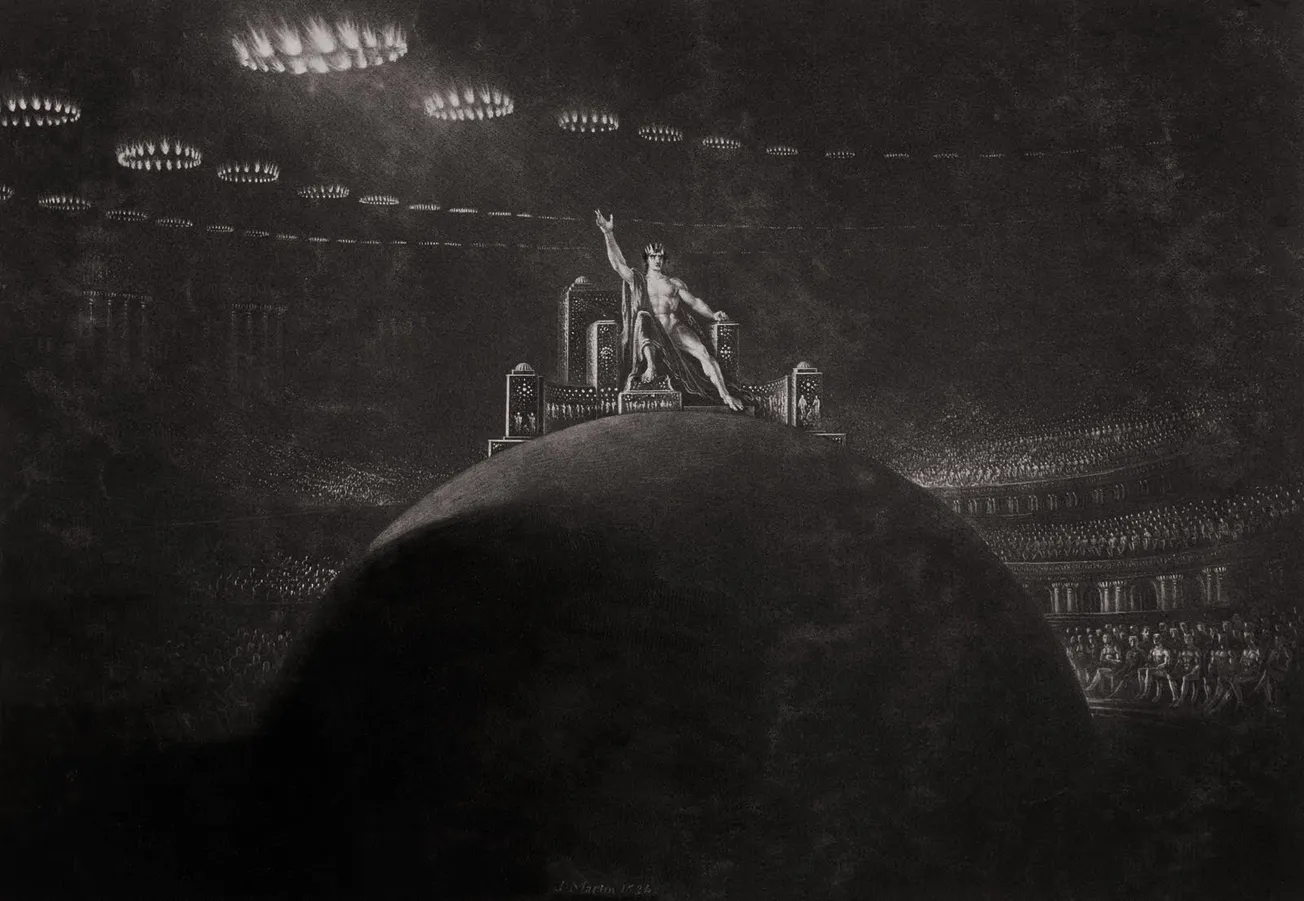

Simons did not deny that important differences exist between the U.S. and Russia. However, he implied that the United States has a harmful tendency to equate the old Soviet threat with modern Russia. When dealing with post-Soviet Eurasia, Simons said, we tend to view conflicts in neat dichotomies of good versus evil, with the Big Bad Russian Bear on one side and its virtuous, defenseless neighbors on the other.

We will always be forced to choose a side which will “be damaging to the U.S. no matter what side we choose,” Simons said.

To avoid this “policy dead-end,” Simons advocated approaching Russia and Eurasia relations from a different angle. In his lecture, he focused on the developing Eurasian states and how understanding their internal dynamics could help the United States propose effective policy changes.

Simons enumerated several commonalities between the developing Eurasian states that are, he argued, just as important as their differences. Compared to the West, civil society is weak. The state still retains such a large role in the economy that Simons noted that NGOs should be more appropriately re-named GONGOs (government-organized non-governmental organizations.) A weak civil society has led to other problems, such as a constant “struggle between post-Soviet elites over access to economic resources,” he added.

Many Eurasian states have also been experiencing a process of state building, giving them the means to push back against encroachments by Russia.

“Nothing is inevitable about Russian hegemony,” Simons stated.

Critical to Eurasia’s nation building is a budding sense of nationalism. There is a choice between developing an “inclusive” nationalism (where one chooses one’s national identity) or an “exclusive” nationalism (where one inherits one’s national identity.) It is vitally important that the United States encourage the former, said Simons, to help curb the temptation for small Eurasian states to favor destructive nationalistic tendencies based on ethno-religious criteria.

Because Eurasian states look toward the West for legitimacy, the United States has leverage in their development. If we promote state development in these countries, Simons said, we can promote democracy in that part of the world. Simons insisted that we can provide a positive influence if we learn to treat Eurasian states as responsible participants in the international community.

“The challenges are serious,” Simons said, “but can be overcome if we can be clear-eyed and serious, too.”

Excerpt: When dealing with post-Soviet Eurasia, Simons said, we tend to view conflicts in neat dichotomies of good versus evil, with the Big Bad Russian Bear on one side and its virtuous, defenseless neighbors on the other.