Table of Contents

The race for Artificial Intelligence (AI) supremacy is, fundamentally, an ever-escalating energy war. China’s centrally planned, dual-track "AI-Energy" policy is establishing a critical, long-term infrastructure advantage that threatens the U.S.’s technological leadership, forcing the West to abandon strict free-market ideology and adopt its own form of strategic state capitalism to compete.

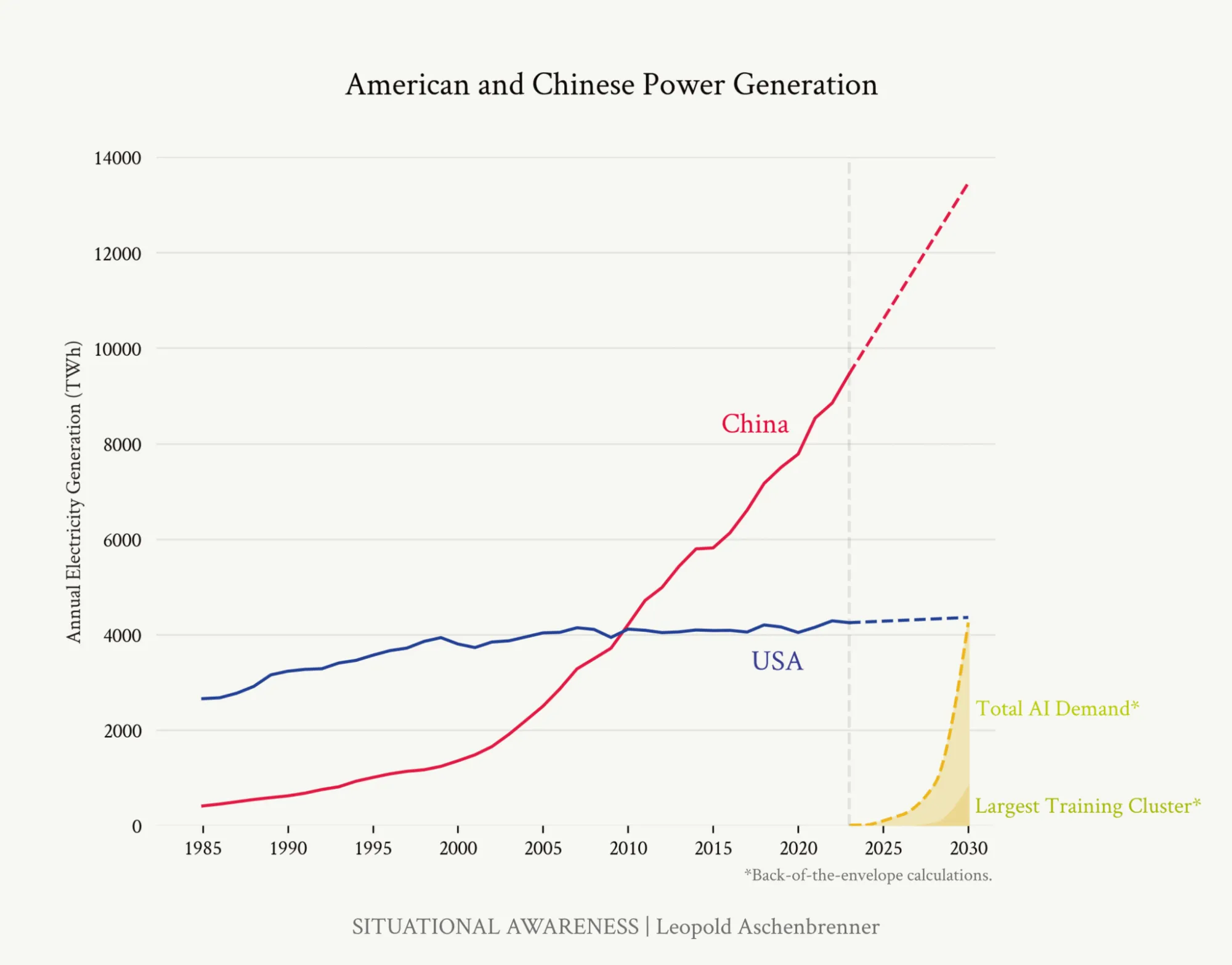

The current limiting factors for AI development – the scarcity of compute and of world-class talent – are increasingly being overshadowed by a far more foundational constraint: energy. It is on this crucial frontier that China holds a decisive advantage.

From the steam engine to ENIAC, the trajectory of transformative technologies is inextricably bound to their power requirements. Indeed, the gap between "technically possible" and "economically viable at scale" is often measured in kilowatt-hours.

Before the emergence of large-scale AI deployment, data centers maintained a stable energy equilibrium, as rising computational needs were balanced by improvements in GPU energy efficiency. However, as Jevons’ Law predicted, this balance was broken when major technology companies (Google, Meta, Amazon, etc.) shifted toward power-hungry processors to run large-scale AI models. For perspective, the training of GPT-4 was estimated to consume over 50 gigawatt-hours (GWh), which is enough electricity to power all of San Francisco for three days. By 2028, AI is projected to consume as much electricity annually as 22% of all U.S. households. America's aging electrical grid and lengthy permitting processes have left the country structurally unprepared for AI's exponential energy demands.

China’s Edge

China has launched what amounts to a Manhattan Project for energy infrastructure, deploying a centrally planned, dual-track strategy that grants its tech sector a decisive edge in the global AI race. While American AI researchers struggle with a fragile power grid, Chinese developers now treat energy availability as a solved problem. China’s energy strategy is characterized by aggressively deploying clean power for future dominance while expanding coal and oil production to ensure immediate stability. This has resulted in unprecedented energy construction. China currently has 32 nuclear reactors under development. The U.S., by contrast, has built two since 2014. China’s solar manufacturing capacity exceeds 1,000 gigawatts. The U.S. capacity stands at 26 gigawatts.

Today's AI leadership reflects yesterday's constraints: talent and capital. But as AI scales exponentially, energy is rapidly becoming the binding constraint that will determine tomorrow's winners. As we approach the era of continuous training on trillion-parameter models and real-time AI agents serving billions of users, energy availability will eclipse talent as the primary limitation.

Professor Shanjun Li, a Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and a Professor of Global Sustainability in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, ascribes China’s hardware advantage to a difference in tech policy and governance. China has mastered an “incredibly sophisticated industrial support ecosystem” that adapts to a sector's maturity. This system, powered by massive state investment, was a critical driver of its global market dominance in solar panels, lithium batteries, and high-speed rail.

Li told the Review that “In the initial phase, the government often provides R&D subsidies to support new ventures. As businesses scale, investments shift to operational subsidies, which help cover the production costs. Finally, as products reach the market, consumer-facing subsidies and rebates stimulate demand.” It is now clear that China’s combination of supply-side and demand-side policies has been a winning strategy.

Furthermore, China boasts a formidable infrastructure supply chain advantage as products are commonly built locally, or even at the factory next door. Aside from lower transportation costs, Professor Li notes that this “allows you to work with upstream suppliers and downstream buyers, and ensure that engineers can collaborate effectively.” Thanks to the intense buildup of complex manufacturing supply chains, China has developed deep process knowledge.

This has further accelerated a key process of “learning by doing.” According to Li, as firms continually produce the same goods, their unit costs come down, as “their workers and engineers learn how to produce the same goods at a lower cost.” China has not only become the dominant global producer of finished goods, but also of the critical components such as solar wafers, inverters, and specialized steel for nuclear reactor vessels. This flywheel effect of state strategy and local process improvement has fueled an ever-expanding energy lead for China.

China’s strategic advantage is not limited to the energy sector. While TSMC’s advanced foundries have granted the U.S. a significant compute advantage for AI training and inference, Professor Li contends that the question of China’s ability to catch up in semiconductors "isn’t about whether, but when, especially under the strict US restrictions on export of advanced semiconductor chips to China."

Dan Wang, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and author of the bestselling book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, observed divergent outcomes in the electric vehicle manufacturing industry. After a decade and an estimated $10 billion, the world’s third most valuable technology company, Apple, abruptly shut down its ‘Project Titan’ car initiative with nothing to show for it. Conversely, the Chinese tech company Xiaomi recently launched its high-performing SU7 electric sedan, after starting the project in 2021. Xiaomi’s rapid success stands as a stark indicator: the West’s traditional corporate models and short-term earnings pressure are being outpaced by Beijing’s integrated, industrial policy-driven speed.

Wang told the Review that China’s EV investment is not out of a moral interest in preventing climate change, but is rather part of a calculated strategic pivot to an energy system powered by domestic resources – whether coal, solar, or nuclear – thereby converting a major geopolitical vulnerability (oil imports) into a strategic advantage (energy self-sufficiency). Wang notes that we now live in a world where “the U.S. builds better powerpoints, as China builds better technology.”

The U.S. Response

China’s dominance in clean energy manufacturing represents a profound strategic threat to the United States. For generations, U.S. industrial strength has rested on its unrivaled capacity for innovation, with the common view being that "the U.S. innovates and China copies." Ironically, the current threat may demand that the U.S. seek inspiration from its rival’s playbook: long-term industrial policy. As Professor Li observes, "The U.S. government needs to provide a stronger, stabler signal. This would help create policy certainty. In a world with policy uncertainty, firms are hesitant to invest. They might just wait.”

To compete effectively, the U.S. must move beyond short-term political cycles and craft a national strategy that provides the policy certainty and economic foundation necessary to rebuild domestic supply chains and manufacturing at a competitive scale. Concrete steps include establishing 10-year federal purchase agreements for domestically produced solar panels and batteries, reducing grid interconnection approvals from the current 3-5 years to under 18 months, and creating manufacturing zones with expedited permitting that can compete with China's streamlined development process.

It is now clear that the Trump administration has been inspired by “the China Model.” This is well-illustrated by the aggressive industrial policy being deployed by the Trump Administration to address the critical minerals chokepoint. Facing a dependence on China for its rare earth imports, the U.S. government is increasingly taking direct equity stakes in domestic producers. The Department of Defense invested $400 million to become the largest shareholder in rare earth miner MP Materials, while the Department of Energy took a 5% stake in both Lithium Americas and its flagship Thacker Pass lithium project in Nevada.

The stark geopolitical necessity of confronting China’s industrial dominance has effectively forced the United States to abandon its strict free-market ideology, instead embracing a strategic form of, in Wang’s words, “state-owned enterprises with American characteristics.” While this shift was designed to secure national energy independence, it represents a pronounced departure from traditional free-market principles, creating a system of competitive subsidization that distorts competitive dynamics.

China’s energy dominance has cornered the U.S. into an existential trade-off: The geopolitical necessity of winning the AI-energy race now requires the nation to set aside its core free-market orthodoxy. To prevent a future where a totalitarian regime controls the foundational infrastructure of global power, Washington has been forced to sacrifice the purity of its principles for strategic survival. Nearly fifty years ago, “I’m from the government and I’m here to help” was Reagan's nightmare; today, it is Trump’s urgent reality.