Table of Contents

A few weeks ago, I confidently predicted a red wave in last Tuesday’s elections. While the results of a few key races are still unknown, it is quite clear that this year’s election will not come close to qualifying as a red wave. I was very wrong. There were certainly some bright spots for the GOP — the impending end of Nancy Pelosi’s possession of the Speaker’s gavel chief among them — but, overall, Republicans significantly underperformed compared to my expectations.

A Fizz post from last week with a screenshot of my article reads, “I just think it’s so funny how the Review was so confidently wrong on this. Is it not personally embarrassing?” I am not embarrassed to be wrong; I put too much weight on Joe Biden’s unpopularity and too little on the messaging and quality of Republican campaigns. In my interpretation of the electoral landscape leading up to November, the focus was in the wrong place.

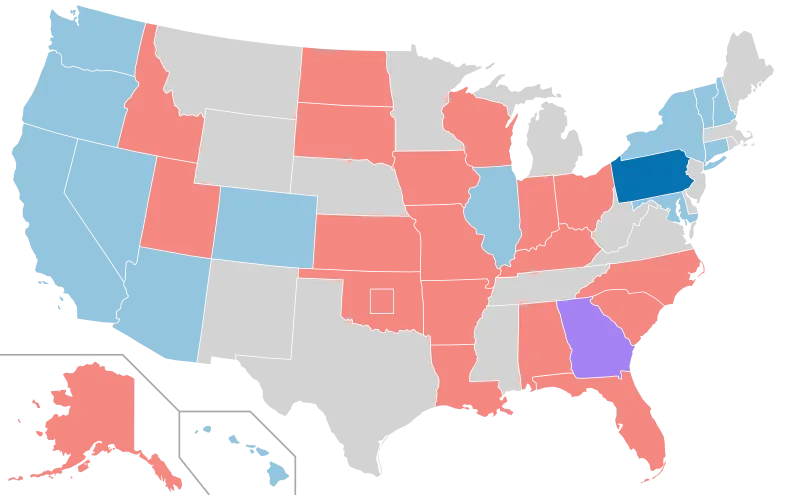

In my original piece, the central thesis was that little about the fundamental political environment had changed since the Republican victories in November 2021, and therefore we should expect a similar outcome this year (i.e. a red wave). This materialized in New York and Florida. Ron DeSantis won by nearly 20 points, even carrying the traditionally-blue counties of Palm Beach and Miami-Dade. Republicans flipped 4 House seats in New York, including the defeat of Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) Chairman Sean Patrick Maloney. However, in the other 48 states, Republican performance ranged from underwhelming to downright awful.

While I certainly haven’t earned the right to chime in on last week’s outcome, I think the GOP’s disappointing night in most of the country stems from the fact that in most races Republicans weren’t really running on any real platform. Comparing GOP successes in New York and Florida this year, Virginia and New Jersey in 2021, and Republican waves of 1994 and 2010 to the broader Republican letdown in 2022 makes this dichotomy quite clear.

New York gubernatorial candidate Lee Zeldin emphasized crime in his campaign. Ron DeSantis highlighted his decisions to keep Florida open during the pandemic. In 2021, Glenn Youngkin won in Virginia on his pledge to give parents more power in their children’s education. In 1994, Republicans took back the House for the first time in a generation because of their Contract With America, a set of Congressional reforms and legislation that fit with the party’s vision for a smaller, more efficient government. Similarly, in 2010, Republicans gained power on a promise to bring fiscal responsibility back to Washington.

Meanwhile, in 2022, by and large there was no coherent national Republican message to voters outside of blaming (though fairly, I’d add) Democrats for inflation and pointing out their radicalism on social issues. RSCC Chairman Rick Scott released a 12-point-plan in February that ended up being so unpopular that even right-leaning groups eviscerated it. GOP House Leadership put out their “Commitment to America” rife with platitudes that were thin on a meaningful vision for what Republican control in Washington would actually mean.

A lot of noise has been made about the Republican party running weak, Trump-aligned candidates in key races, including Herschel Walker in Georgia and Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania. While candidate quality certainly makes a difference on the margin, Republicans should not convince themselves that their candidates were the problem. Ron DeSantis is no moderate. Moreover, an attendee of the January 6th protest was elected to Congress in a New York congressional district that voted for Biden by fourteen points. Meanwhile, former Nevada Attorney General Adam Laxalt — a relative moderate — lost Nevada’s Senate race, a state which Biden only carried by two points. The election results point to a deeper issue.

The question of whether the Republican letdown was a function of losing persuadable voters, failing to turn out their base, or a combination of the two remains to be seen. Votes continue to be counted due to absurd election laws and procedures in certain states. But looking at the past decade of politics, campaigns succeed when they lay out a few key priorities that motivate their base to show up and convince so-called swing voters they should be trusted to man the levers of power, rather than preserving the status quo.

Yes, Joe Biden may be an inept President and Democrat policies might be completely decoupled from reality. I thought that would be sufficient to propel Republicans to victory last week. But the numerous high-profile losses make it clear that until the Republican Party can decide on what it stands for (rather than just what it stands against), Democrats will continue to win elections in competitive states, regardless of their candidates’ ability to string enough words together to form a sentence.