Table of Contents

Fake news is as old as America itself. History will demonstrate that this phenomenon poses no great threat to journalism, or truth in society. It is nothing more than a temporary side effect of the rise of politicians who challenge the establishment in the name of the people. Distinguished Americans from Benjamin Franklin to William Jennings Bryan engaged in the practice we call fake news, and while we may justly deplore their means, their actions demonstrate that the end of fake news is most often a noble one: to serve as a correction to an elite that has grown detached from the popular will.

Most Americans would be shocked to learn that the discoverer of electricity himself once forged a newspaper to realize his political goals. Just after victory over the British was sealed at Yorktown in 1782, no less an American hero than Benjamin Franklin carefully faked an entire issue of the Boston Independent Chronicle, filling pages with blatantly false stories about American colonists being scalped on British orders—all in an attempt to appall the British public and thus secure favorable concessions from England. In his attempt to undermine the sovereignty of a foreign government, Franklin was in this instance no better than Buzzfeed’s infamous Macedonian fabricators of fake news stories or, for that matter, the Russian operatives who allegedly sought to manipulate American policy through appeals to the American public. Franklin, however, must have seen himself as acting in the interests of his young nation, and the families of Americans who had been killed or seen their property destroyed in the Revolutionary War.

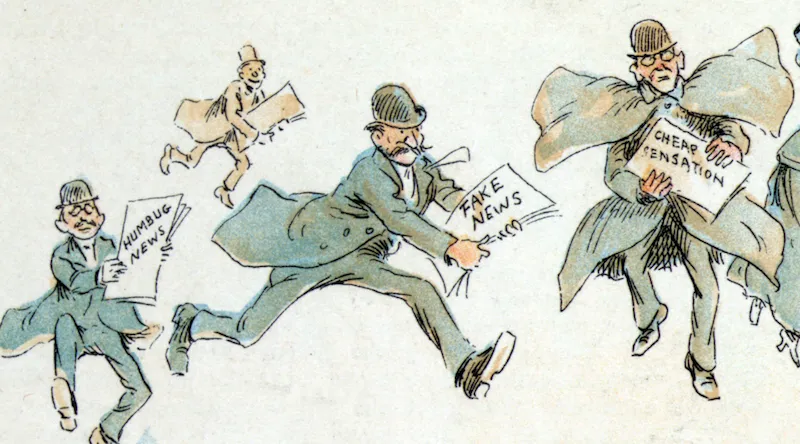

Evidently, fake news has a much longer history than is commonly acknowledged. Even the phrase “fake news” has been used in a political context since at least 1894. In the American fin de siècle, accusations of false rhetoric flew fiercely around the figure of William Jennings Bryan, the so-called “Great Commoner” and most successful American populist since Andrew Jackson. The Iola Register denounced the “miserable fake news” that claimed Bryan’s victory in the 1896 election (in fact, he lost to McKinley, as he would again in 1900), while a dismayed Davenport Daily correspondent seemed to fear the subversion of trust in journalism, stating, “It could not be foreseen that a time would come when whole columns of fake news would be [both] printed and read.”

The contemporary phenomenon of fake news consists of two major aspects: first, misinformation; second, attacks on the credibility of established journalistic outlets. William Jennings Bryan, like Donald Trump, has been associated with both. Bryan founded a newspaper in Lincoln, Nebraska in 1901, called The Commoner. In 1907, the paper criticized the established presses’ skepticism of Bryan’s opposition to a third presidential run by Teddy Roosevelt. In a clear move to undermine the credibility of mainstream journalistic outlets among its pro-Bryan readership, the paper proclaimed, “There seems to be an epidemic of fake news from the city of Lincoln.” This people’s champion—who fought his own party’s establishment in an attempt to secure a monetary policy he believed would make life easier for poor farmers and workers—seems not to have been above the sort of standards-undermining maneuvers which, we are now told, threaten the existence of truth itself.

Neither Franklin’s nor Bryan’s efforts resulted in a cataclysmic loss of truth in American society. On the contrary, the same period in which Franklin made his forgery saw the publication of the monumental Federalist Papers—in the form of newspaper op-eds. Bryan’s political career took place during the Progressive Era, a golden age for muckraking investigative journalists. Perhaps in part because of their heightened democratic energy, these periods proved high-water marks for the journalistic habit of “speaking truth to power,” which contemporary fake-news critics justly cherish, and fear losing. History has not seen fit to magnify the importance of a few blemishes, in the form of rumor and forgery, that accompanied the greater triumphs of the age.

Both these episodes of fake news in American history arose as a reaction against a political elite whose members did not have the best interests of the American people at heart—be it Franklin’s British aristocracy or Bryan’s financial elite. Might not today’s outbreak of fake news signal that we are presently experiencing a similar period?

Two eminent political scientists recently argued in Foreign Affairs that the “liberal order is rigged.” While well-educated Americans have seen their incomes swell, the incomes of poorly-educated Americans have fallen by a quarter in recent decades. Little in the way of a safety net exists to catch those whose boats have not been lifted by an ostensibly rising tide. The two authors admit they had been blind to this problem until the rise of populism and fake news alerted them to a larger, uncomfortable truth. Similarly, as the 2016 election went on and worries about fake news piled up among the American elite, the New York Times ran a grudgingly positive review of J.D. Vance’s book Hillbilly Elegy: a memoir about the white rural poor in Appalachia, one of many groups seemingly excluded from this liberal order. It is not unreasonable to suggest that fake news may have helped jolt the Times into gritting its teeth and extending greater attention to segments of the American people it had long been more content to ignore.

It may be contended that the rise of new media through platforms such as Facebook has transformed fake news from something innocuous to a genuine threat. This view, while understandable, should be considered disproportionate and ahistorical. If the speed and volume by which these stories can be transmitted has increased, it is only because the speed by which all information travels has increased. Today, a trumped-up story may reach a million pairs of eyes instead of ten thousand, but never again will an entire town be hoodwinked by a report that the wrong presidential candidate has won—as the readers of the Iola Register were by false reports of Bryan’s victory over Taft in 1896. The reach of fake news stories online has, moreover, been much exaggerated: Stanford political scientist Morris Fiorina argues in his new book that these stories reached only a small fraction of Americans during the most recent election cycle.

The proliferation of false stories and attacks on reputable media outlets may make us uncomfortable, but history demonstrates that there is little to fear in terms of long-term erosion of societal norms. Instead, the return of fake news should be recognized as a normal feature of a society undergoing democratic reinvigoration within a market of ideas and media. If a decadent establishment is being shocked into re-engagement with the people it represents, the positive consequences of this transition will outlast the temporary unpleasantness of fake news. If we are indeed the good democrats we profess to be, we should find the strength to take a modicum of joy in the notion that a popular fury has been unleashed on an American elite which is at least as complacent as that of 1894.