Table of Contents

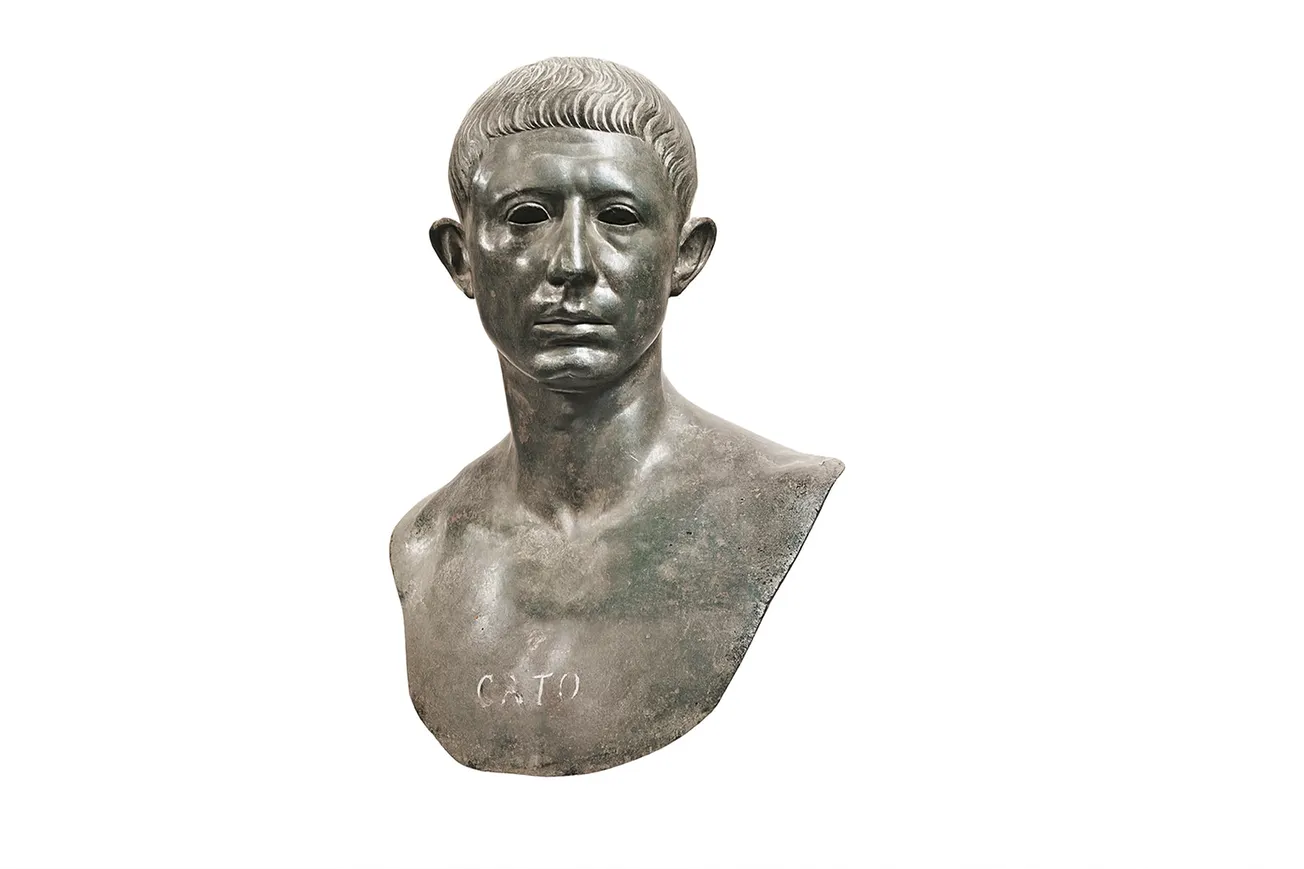

The Roman statesman Cato the Younger stands as one of the most universal and powerful images of Western conservative thought: a martyr for liberty, a stalwart and sometimes too unyielding politician, and the stoic of stoics. In an age of political turbulence and institutional decay, his legacy poses a moral challenge that the American right cannot afford to ignore. To preserve our institutions, our values, and our liberty, we must recover the spirit of Cato.

Cato, the historical figure, was undoubtedly not the character ancient writers like Plutarch paint—he was a Roman politician, vain, ambitious, and inflexible. But the enduring image of his principled defiance, forged by the moralizing of ancient sources, has shaped centuries of conservative thought and inspired a tradition of admiration in the Anglosphere. The Cato Institute takes its name from the inspired pseudonym used by English writers in the 1720s to condemn the tyranny of the British monarchs. The American Revolution’s rallying cries—“Give me liberty or give me death” and “I only regret, that I have but one life to give for my country”—have been traced back to the contemporaneously popular British play Cato, a Tragedy, one of George Washington’s favorites.

Above all, Cato’s gravitas came from his austere personal conduct. As Sallust observes in The War of Catiline (54.1):

Caesar was held great because of his benefactions and lavish generosity, Cato for the uprightness of his life. The former became famous for his gentleness and compassion, the austerity of the latter had brought him prestige.

Among the aristocratic political circles of the Late Roman Republic, excess, licentiousness, and ego were the order of the day. But Cato’s actions were also guided by the virtue he understood to derive from unbending justice. A noted Stoic, he sought to present himself as living simply by exercising compulsively, devoting himself to public service, and dressing in dark, unostentatious clothing. In most of his public and private dealings, he made a point to be strictly scrupulous and honest, remarkable amid the pervasive bribery which defined Late Republican politicking.

Despite a reputation for fiery rhetoric, Cato retained the respect of his opponents: as Plutarch recounts, “on the tribunal and in the senate he was severe and terrible in his defense of justice, but afterward his manner towards all men was benevolent and kindly” (Plutarch, Life of Cato the Younger, 21.5). Through his image of irreproachable virtue, Cato sought, as Professor Fred Drogula puts it in his excellent biography, to “promote himself as the man who best embodied the mos maiorum,” the ancestral customs of Rome. And his staunch commitment to defending these values and the Republic would define his memory.

Just as in his personal life, Plutarch presents Cato as vocally committed to a fierce form of conservatism in his public actions. He delivered a balanced budget, quickly paid out the state’s debts, cracked down on corruption, and staunchly opposed the First Triumvirate, which aimed to concentrate political power at the expense of the senate and traditional political norms. Even at personal cost, he stuck by his convictions; after delivering a speech against a bill seizing land for redistribution, he was dragged from the forum to prison by populists acting under Caesar’s orders. While Cato’s uncompromising form of conservatism often isolated him, we ought to admire the value he placed on tradition, country, and service.

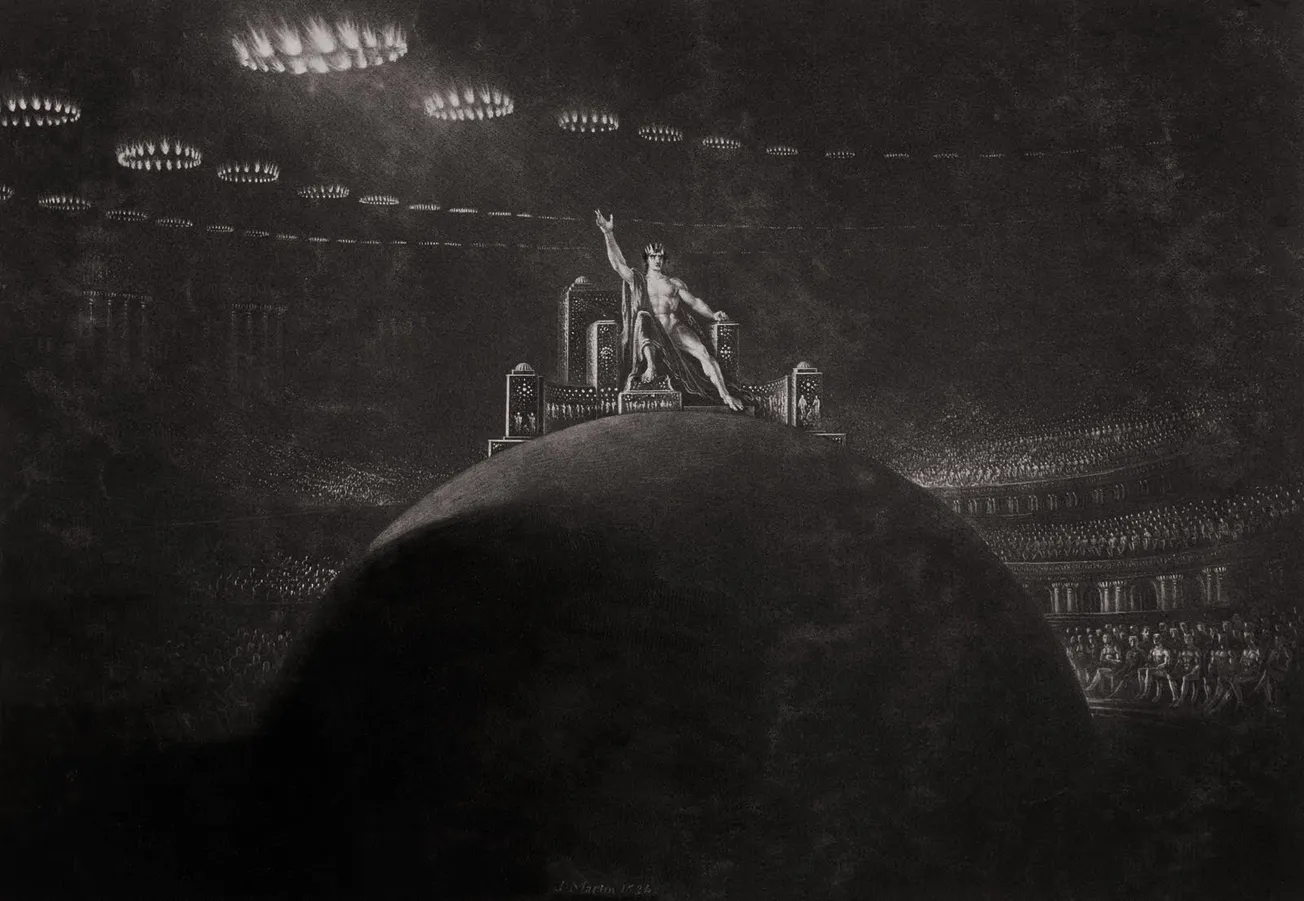

But by far Cato’s most enduring quality was his unshaking commitment to liberty in the face of crisis. Even as the street thugs of the First Triumvirate and the troops of Caesar’s legions during the civil war sought to silence him, he served as the loudest and boldest advocate of the traditional political rights afforded to Romans. For Cato, liberty was not merely a political ideal but a moral duty. As Caesar’s forces closed in on Cato’s headquarters after defeating Pompey in the civil war, Plutarch records him insisting that by refusing to give in to a tyrant, he remained the “conqueror of Caesar in all that was honourable and just” (Plutarch, Life of Cato the Younger, 64.5). He would commit suicide in agonizing fashion shortly after, stabbing himself in the chest and tearing out his own intestines to avoid falling into Caesar’s clutches, despite the latter’s offer of clemency.

In an age where America is experiencing its own epidemic of political violence and turbulence, the conservative movement and the Republican party need more of the spirit of Cato—probity, ideological commitment, public service, and an unyielding belief in what he saw as liberty. Like Cato, we must fight our hardest as the guardians of the rights of all Americans. But unlike him, we must prevail.