Table of Contents

AI might automate a third of jobs in the next six years.

True or not, concerns over mass automation and unemployment have united tech leaders like Elon Musk and OpenAI with diehard leftists in supporting a universal basic income distributed to all American citizens. Yet despite this diverse coalition, most UBI proposals - like Andrew Yang’s - unfortunately just layer UBI on top of our bloated welfare system, tinkering with Social Security while leaving the tangled mess of means-tested welfare untouched.

UBI proponents have an epochal opportunity to rethink this policy choice and to achieve the first progress against poverty in 60 years.

Because the best case for UBI isn’t really about UBI. It’s about a simple, stunning statistic: the poverty rate today is higher than it was in 1975.

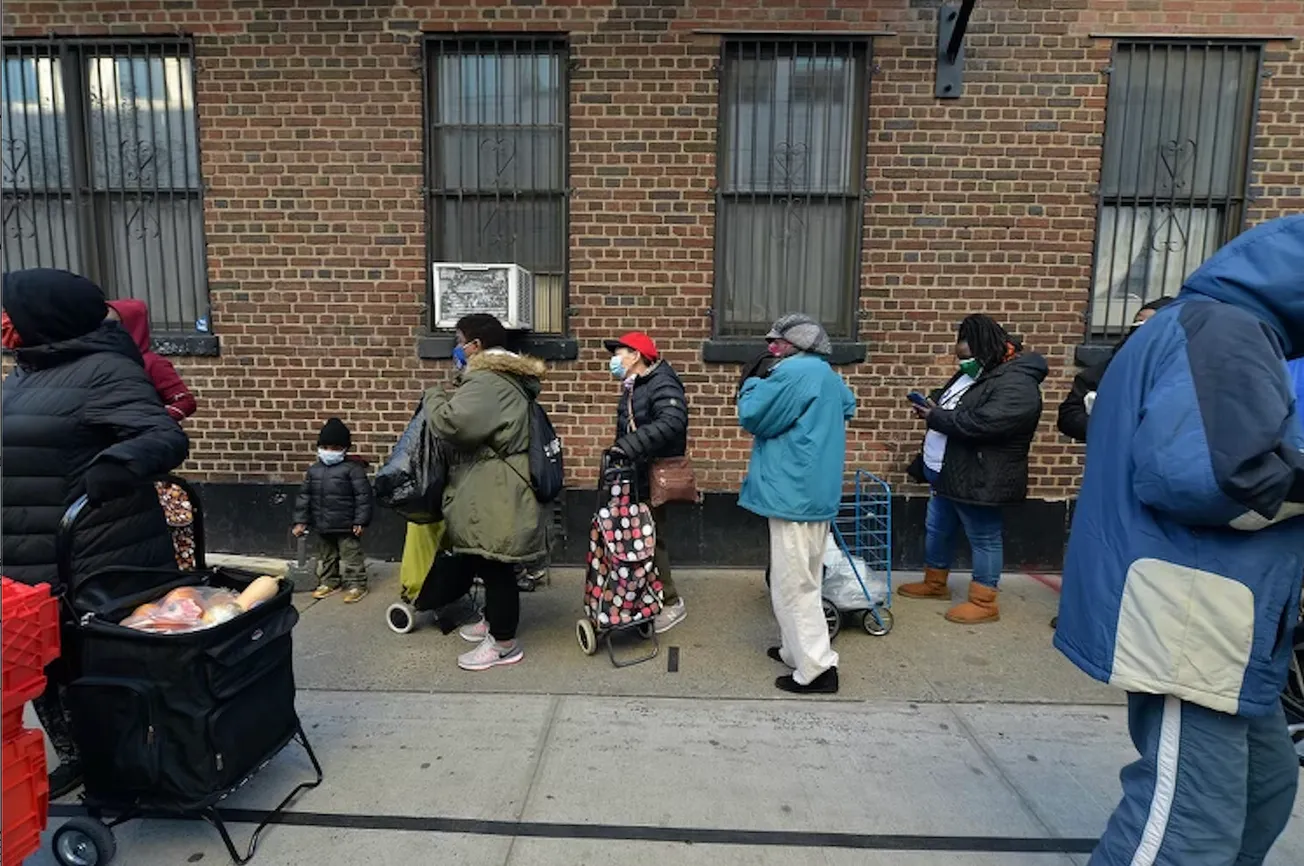

Think about what this means. Six decades into the War on Poverty, welfare spending has exploded from virtually nothing in 1965 to a staggering $2.4 trillion each year. The government now spends $64,000 annually per welfare recipient. In the interim, technological progress has multiplied the American GDP many times over. Yet since 1965, the poverty rate has dawdled between 11% and 15%, and in absolute terms, the number of Americans in poverty has soared, despite this massive spending.

Or rather - because of it.

Most welfare spending is swallowed by a byzantine bureaucracy spanning hundreds of agencies. What remains fuels income and asset traps that punish welfare recipients for striving to escape poverty. Instead of a safety net, welfare has become a spiderweb that ensnares millions into lasting and intergenerational poverty, creating a sort of hereditary serfdom.

Repealing welfare and replacing it with an intelligent UBI along Milton Friedman’s lines — direct cash payments that gradually phase out as income rises — will abolish this overgrown bureaucracy and eliminate its perverse incentives. It will end poverty overnight. It will empower former welfare recipients to build their own futures and break the cycle of dependence. And, almost unbelievably, it will do all this while saving money.

Consider the numbers: America spends $2.5 trillion annually on welfare - $1.6 trillion on federal Medicaid and income security, and another $862 billion at the state level. This figure doesn’t include Social Security, Medicare, education, or social services like drug rehab and child protection.

Yet even within this narrow definition of welfare, the money is there to guarantee every American a minimum income of $18,000 per year, wiping out official poverty overnight. On average, this UBI would provide $9,000 in assistance to the 75% of Americans - 250 million people - making less than $75,000 per year. As people earn more, the benefit would phase out gradually at a marginal rate of 25%, meaning that for every $4 gained in income, only $1 of UBI would be reduced.

After all that, we’d still have roughly a quarter-trillion left over each year to bolster underfunded programs like Social Security or education.

This seemingly magical math is possible in part because of the vast bureaucratic blubber we could cut. For instance, at the state level, 97% of welfare spending is “operational”, meaning it’s funneled into the poverty industrial complex - contractors, administrators, overhead - instead of going directly to the people who need it.

Some waste is just plain graft: an overpriced contract to a friend here, a billion-dollar boondoggle with IBM there.

Much of it is sheer inefficiency. Overlapping agencies duplicate work. Onerous, routine means-testing piles on costs. Take drug testing: $200 per test, multiplied over millions of applicants, adds up to tens of billions for one small aspect of this sprawling bureaucracy. All the while, poor technology, confusing forms, and constant recertifications squander bureaucrats’ and welfare recipients’ time alike, requiring hundreds of thousands of employees just to administer benefits.

Exactly how much is wasted is impossible to pin down - what even qualifies as “waste” in a system so convoluted? But when we’re spending $64,000 per welfare recipient, and they remain in poverty, there’s colossal waste somewhere.

Replacing this system with UBI obviates these administrative middlemen. With a single, lean bureaucracy — likely the IRS, as with the Earned Income Tax Credit — cash could be distributed directly to citizens.

This windfall from eliminating administrative waste pales in comparison to UBI’s long-term, transformative impact: freeing welfare dependents from income traps, asset traps, and the uncertainty of benefits, empowering them to escape the current system’s perverse incentives.

The crux of the problem is that welfare benefits are tied to specific means-tested criteria. When recipients earn just above a certain threshold, they lose multiple benefits at once. These sudden drops - these income cliffs - create a harsh tax for earning more, where increasing income can leave people financially worse off than before.

This is the income trap: recipients work harder but get stuck in a cycle where they are left with virtually no additional income because every gain triggers a benefit cut. On federal programs alone, welfare recipients can experience a staggering 95% marginal tax rate, meaning that for every $1 in extra income, 95 cents are lost to benefits cuts. In some cases, accounting for state-level benefits caps, people face marginal tax rates of over 100%, losing more in benefits than they gain from working. Much less extreme rates suffice to trap millions in poverty, because as a UChicago economist eloquently explains, “the sacrifices that jobs require do not disappear. The commuting hassle is still there, the possibility for injury on the job is still there, and jobs still take time away from family, schooling, hobbies, and sleep. But the reward to working declines.”

Welfare dependents can’t work their way out of poverty; they also save their way out of either, because they risk losing critical benefits all at once. Certain disability aid programs, for example, limit individuals to $2,000 in assets - including savings, cars, and rent deposits - forcing them to quickly spend away their income to avoid losing their benefits. Even modest windfalls can be devastating; one man who found $800 on the ground lost his Medicaid coverage.

And because of the uncertainty surrounding benefits, welfare recipients often can’t afford to risk sacrificing current benefits for future income, even if they want to. Many benefits, like New York City’s rent-controlled housing, are notoriously difficult to regain once lost, as they rely on lotteries or exhaustive documentation. If someone tries leaving the system and fails, they risk falling through the cracks, losing essential benefits like food, healthcare, and housing. It’s a gamble nobody can afford.

By contrast, the UBI proposal phases out gradually - $1 for every $4 earned - and has no wealth-based phase-out, allowing people to earn more and save towards durable wealth, the best foundation for intergenerational growth. With UBI, there are no cliffs, just a steady path forward.

When the current system is this enormously inefficient and perversely incentivizing, the common arguments against UBI don’t hold up.

Some argue people won’t work with a UBI. But a guaranteed $18,000 yearly is only enough to survive, not live comfortably. Poor Americans will still have every reason to work, but unlike today, they can do so without the fear of losing benefits by earning too much. In a system that currently disincentivizes hard work, UBI’s neutral incentive structure is undeniably better.

Others claim money will go to those who don’t need it. But it’s an open secret that welfare benefits, like rent control, often go to the politically-connected rather than those truly in need. In contrast, UBI would only go to Americans earning less than $75,000 a year. With almost 2 in 3 Americans unable to cover a $500 emergency expense, it’s clear the overwhelming majority would need the money.

One of the most common concerns is that poor Americans, especially drug addicts, will waste UBI’s no-strings-attached cash. This counterargument too misses the mark. Drug addicts and others requiring specialized help are already covered under separate social services like rehab programs, which this UBI does not touch. And for everyone else, when UBI pilots actually give lump sums of cash to poor Americans, recipients overwhelmingly spend on productive things like paying down debt, not drugs and alcohol. Given the welfare bureaucracy’s wastefulness, opposing a UBI in favor of the current system is a bit like handing your money to a drunken sailor to avoid overspending on your next Costco run. Welfare is certain waste; UBI is, at worst, a possibility of waste.

In sum, layering a UBI on top of the current welfare system misses the point. It might push the poverty line up slightly, but it can’t fix the core issues of welfare’s grotesque inefficiencies and perverse incentives.

The real power of UBI lies in repealing and replacing modern welfare.

We would end official poverty overnight.

And in the long run, we would free millions of Americans from the serfdom of a Kafkaesque bureaucracy, unlocking their potential to improve themselves and contribute to the economy.

Imagine the innovation and the economic growth when a large portion of the population - currently trapped in severe underemployment - is, for the first time in 60 years, finally free to dream big and pursue new opportunities.

So maybe ChatGPT’s greatest achievement won’t be in automating coding or customer service. Perhaps it will be that, in stoking fears of automation, it paved the way for UBI.