Table of Contents

Steve Blank is a Senior Fellow at Stanford's Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation, where he operates at the intersection of tech innovation and national defense. A veteran of the Air Force and eight startups, Blank revolutionized modern entrepreneurship as the architect of the Lean Startup movement. His seminal works, The Four Steps to the Epiphany and The Startup Owner's Manual, remain the foundational playbooks for building companies. Today, Blank teaches at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and School of Engineering, leads Hacking for Defense, and mentors for the NSF’s I-Corps.

This conversation follows Blank as he examines entrepreneurship as artistry, AI's challenge to the startup playbook, and the innovation contest that will define the century: Private Equity versus the Communist Party. Despite the high geopolitical stakes, Blank finds a profound source of optimism in the "incubator with dorms" that is Stanford.

The following interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

Jack Murawczyk: You dropped out of Michigan State, hitchhiked to Miami, loaded racehorses onto cargo planes, and enlisted in the Air Force during Vietnam, all before 21. Eight startups and a few decades later, you codified the Lean Startup. What’s the through-line? Where does this restless drive to operate at the frontier come from?

Steve Blank: As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to see that the common thread for me was service. So then you have to ask: service to what?

When I was an entrepreneur, it was service to myself: how can I make a pile of money and feed the family? But as you get older, you realize that, to live a full life, service has to extend outward. Service to God, to country, to community, to family.

When our kids left for college at 18, my wife and I looked at each other and said, Great, we can go anywhere we want for the holidays. We told the kids we were going away for Christmas. They went ballistic: they said, Holidays are for our family. They’re now in their 30s, and that was when I realized you don’t get your report card as a parent until your children leave home.

On community: We live on the coast, and I was a public official for the state of California for seven years as a coastal commissioner, helping preserve a meaningful stretch of coastline.

On country: I served during wartime in Vietnam, and I’m serving again now in a different capacity for national security on the Defense Business Board and on the Navy’s Science and Technology board.

On God: that’s been expressed through my participation in the Jewish community.

When I was young, I wasn’t wise enough to think about any of this consciously; I was just doing it. But you asked for the common thread, and that’s it: service.

JM: Where do you most sharply disagree with the consensus view on entrepreneurship and innovation today?

SB: People confuse execution – being great at making something scale – with the ability to see over the horizon. The latter is a pretty rare trait. That was Elon Musk. That was Steve Jobs. We call them visionaries.

Founders are closer to artists than to any other profession. Artists see things others don’t. Composers hear things others don’t. Writers can imagine entire novels. And the truly great ones don’t outline or iterate their way to the vision. They already hear the symphony. They already see the sculpture.

The story goes that people would visit Michelangelo’s studio and find a twelve-foot block of marble. They’d come back three years later to find the Pietà and ask, How did you do that? And he’d answer: I simply removed the stone around it. That is precisely how a Jobs or a Musk operates. They envision the world as it’s going to be and simply remove the marble around it.

That made it incredibly frustrating for me when I was sitting on defense boards alongside world-class executors. They didn’t appreciate or understand what to do with people who were seeing way beyond the horizon. The result is the impedance mismatch between innovators and executors you see constantly in large organizations.

The artist-innovator analogy matters because it reframes what we’re asking when we talk about entrepreneurship. Founders are not accountants. You can teach accounting. The open question is whether you can teach someone to see the form inside the marble before it’s been touched.

JM: Can you? To what degree is it hereditary?

SB: It’s funny – when I started teaching entrepreneurship here at Stanford, Jon Rubinstein, who used to be the head of hardware at Apple, said: Steve, you were a born entrepreneur. You can’t teach this stuff. And I said: Well, Jon, then why am I doing it?

We discovered about 150 years ago that it’s probably good for society to teach art appreciation to everybody. It made everybody genuinely appreciate how difficult those crafts are, and it helped a small subset of students realize: wait, writing is a career? Painting is a career? Holy cow, I love this. Without that early exposure, you miss both the societal value and the chance to identify the small segment that has the innate interest and talent.

So what does that have to do with innovation and entrepreneurship? If we believe founders are closer to artists, then we should be teaching this in grade school, not because we want everybody to be a founder, but because we want to identify early who has that innate talent and interest.

We have art teachers. Why don’t we have innovation teachers? If you want to change the trajectory of a country and make it an innovation nation, that’s where I’d start.

JM: On that point, you wrote in Nature that the U.S. is “dismantling the very infrastructure that made it a scientific superpower,” drawing a direct line from basic science to economic power. You’ve compared America’s trajectory today to Britain’s loss of scientific dominance after the World Wars. What needs to be done in America to retain our status as a superpower?

SB: We need people in the executive and legislative branches who can articulate the difference between a scientist, an entrepreneur, and a VC. If you don’t, you start asking: What do I need basic science for? Why can’t startups do this?

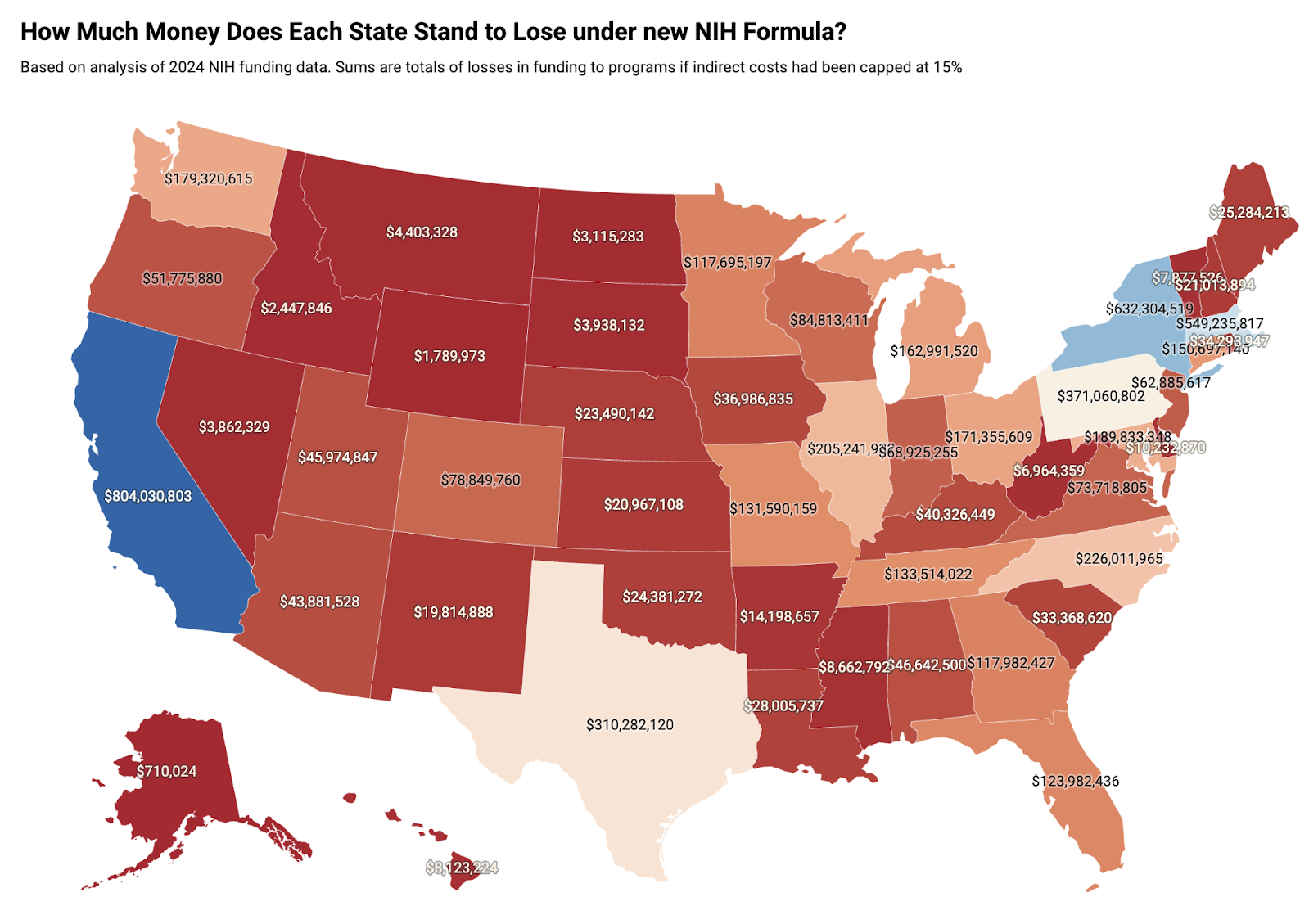

If you don’t understand the distinction between basic research and applied commercialization, you ask: why have we been spending all this money for 80 years? What has the country gotten out of it? Capping indirect cost recovery at 15% at universities becomes, in practice, a decision to kill basic research at universities.

There was nothing that guaranteed that Britain or Germany would be leading the world in the 21st century, and now they’re not. At this point, we lead until we decide not to.

This reminds me of the story of the Chinese Treasure fleet in the Ming Dynasty in the 1400s. China built these massive ships and sailed around the world collecting treasures. Then, for political reasons, they burned the ships, and 400 years later, the West came in and kicked their ass and made them smoke opium. That’s what we decided to do: burn the fleet.

JM: So what policy changes would you make to safeguard and right the ship?

SB: This administration believes that DEI has gone too far: Berkeley and the UC system previously mandated DEI statements for faculty hiring. The administration’s solution to correct this has been to pressure universities by reducing and/or withholding their science funding.

This is the moment to fundamentally rethink how we invest in science, given what is now possible with AI. Instead of a DEI statement, I would insist that every lab articulate its AI plan. It’s an opportunity to rethink the entire process of university research.

JM: The Lean Startup was born in the software era. But many of the most consequential companies today are in the world of atoms, not bits. Hyperscalers are projected to spend $700 billion in CapEx this year for data centers, GPUs, and power infrastructure. Nuclear startups, semiconductor fabs, and defense hardware all have production cycles measured in years and CapEx requirements measured in billions. How does the Lean Startup methodology adapt to the world of atoms?

SB: The current approach doesn’t scale exponentially forever. So some of the more interesting investments are in alternative computing models – neuromorphic computing based on biology, new algorithms, and hardware – that could make things not 20% more efficient, but orders of magnitude more efficient.

Right now, the entire industry is racing to scale one model of how you build and train large language models, but there are other approaches that might make us look back and giggle.

It’s worth remembering that this whole thing is only two years old at this scale. There is an arms race underway. If the world is already investing trillions of dollars in the current approach, a few billion dollars should be going toward something fundamentally different. That’s exactly where NSF and government science funding should be placed.

JM: What happens if there are diminishing returns to scaling laws?

SB: The thing I’d be watching for is AI writing the next generation of itself. At that point, there’s no limit to scale. I don’t think the singularity will come in the way people imagine, but I would call that a singularity. I lived through the first microprocessors, the first PC companies, the first internet companies. But this will be different. This will be bigger.

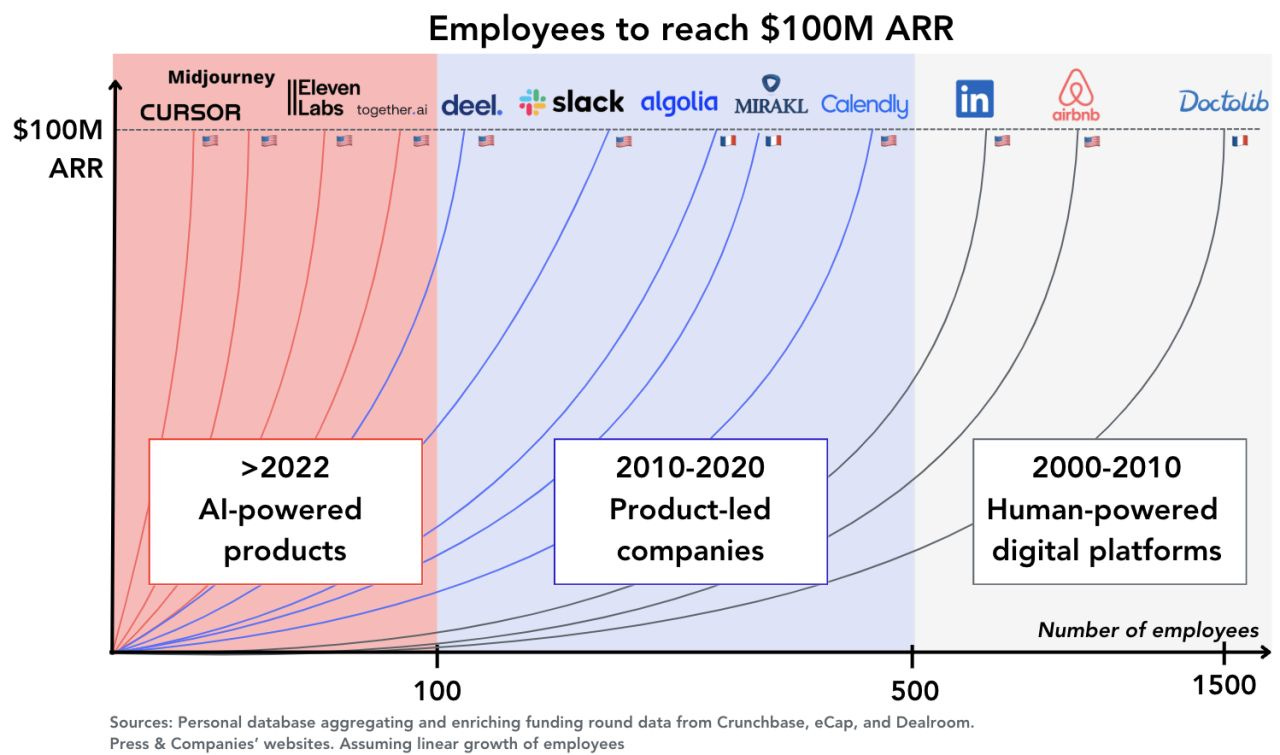

JM: On that note, Anthropic built Claude Code, which became a billion-dollar product, in six months; then used Claude Code to build Claude Cowork in 10 days. Does AI make the Lean Startup method even leaner?

SB: Lean was just a set of simple observations that I could explain today in 30 seconds. All you have on day one is a set of untested hypotheses. No business plan survives first contact with a customer. There are no facts inside the building, so get outside. It took me three years to think out because it required a whole new language. It turned out to be fundamental for the last 25 years. Whether it remains fundamental in the age of AI isn’t yet clear.

This year, I insist all our students in the Lean LaunchPad and Hacking for Defense (H4D) classes use AI – if you’re not using it, you’re not even getting into the class. I want to see your applications done with it. We used to say, Build a business model and show me your product. Now, I want to know: What prompts did you use? How did you use AI? At H4D, we once expected ten customer interviews a week, now it’s a lot more.

JM: Just use ListenLabs!

SB: I was incredibly surprised that the Lean methodology lasted 25 years. My intent was never to start a movement. It was simply an attempt to explain the world as it actually was. You have to understand that in the 20th century, VCs told startups to be smaller versions of large companies and do everything a large company did. And in hindsight, you wonder how anybody ever went public!

My instinct is that what’s needed now is fundamentally different, but I haven’t yet gotten my head around what’s next. It will probably come from someone very different. It took me getting out – back then, I had retired, I wasn’t beholden to VCs, my head wasn’t down doing a startup – I had enough perspective from sitting on public and private boards to start seeing patterns. It’s going to take someone like that: someone incredibly conversant in Claude and all the other tools who realizes it’s not a faster version of the old thing but something fundamentally different. We need new language, new models.

I’d feel bittersweet about it, but I’m hoping somebody does that. I’ll be first in line to congratulate them. I never expected to create something with this much longevity or this much impact.

JM: What should Stanford students know about how commercial technologies like AI, semiconductors, and energy are reshaping competition across all elements of national power?

SB: All our advanced logic chips come from TSMC in a province that China calls the breakaway province – Taiwan. If we lose that, the Western economy goes with it. The punchline is: we could possibly go to war over two nanometers. Semiconductors are the oil of the 21st century. We went to war twice over oil, except this time it won’t be with Iraq; it’ll be with a peer.

Another example of technology’s impact on society is the persistent surveillance of Americans. Every AI doorbell we put in place is now a surveillance node. And there are no longer real barriers to subpoenas; the IRS has already shared data with DHS. So there’s a serious internal problem about civil liberties, and AI is only going to make that worse.

And then there’s an even more interesting problem: disinformation. Unless we have a government that cares, we’ve basically removed all the doorstops. Since the last election, disinformation is now uncontained. So the question is: what do we teach at Stanford? How do we train students to operate in a world of disinformation, persistent surveillance, and potential global wars over technology?

Two years ago, I got invited by the UK Foreign Office to talk about AI regulation. It was a very British affair. And I told them: you’re confused. The toothpaste has already left the tube.

JM: But you need to be GDPR compliant!

SB: They are competing with American companies, facing no rules. And that was before the hundreds of billions of dollars in investment. Do you know how many major AI data centers exist in Europe? Zero. There’s no capital there.

In Darwinian capitalism, both the American and Chinese versions, that’s where tech is going to be at the bleeding edge. It’s not that other countries won’t do interesting things, but the global picture is clear. Every once in a while, I get called by someone in Europe who wants to know what I think. And I tell them that you need to get out of the building more.

JM: Your “Secret History” thesis is that Silicon Valley was built by defense dollars, with Fred Terman, DARPA, and the CIA essentially acting as venture capitalists. China appears to be running its own version of this playbook today. How do you compare China’s innovation strategy to the one that built Silicon Valley, and where do you think the competition goes from here?

SB: When China decided to pioneer innovation, they visited different places in the US and chose to adopt the Israeli model. Israel, remember, was a socialist nation that became an innovation nation. They wrote the book on it, literally.

But China wasn’t doing this in the late 1980s to build a commercial system. Rather, they were partnering with other countries, including Israel and the US, to build up their military and science technology. What accidentally came out of that was a commercial ecosystem, just like Silicon Valley started with microwaves and defense and stumbled into semiconductors. China’s ecosystem was built to support national security, and when the commercial stuff sprang up alongside it, they weren’t quite sure what to make of it. When I first went to China, venture capital was still a novelty there.

In China today, there’s military-civil fusion, which means that everything a commercial company is working on must be offered to or understood by the military. In fact, there has to be a Communist Party representative inside your company. That’s a fundamentally different system. In the US, we don’t do it through coercion, but we’re starting to do it through incentives.

What’s happened since the second Trump administration is essentially that private equity has acquired the defense acquisition establishment. The Deputy Secretary of Defense, Steve Feinberg, was the CEO of Cerberus. The Secretary of the Army, the head of the Navy – all ex-private equity. So they came in and did a private equity roll-up. They looked at all these siloed organizations and threw out 3,000 pages of acquisition rules. What matters is delivery at speed.

This is a battle between Private Equity and the Communist Party.

JM: A core mantra of your teaching is “There are no facts inside your building, so get outside.” Stanford students spend four years on one of the most idyllic campuses in the world. How do you suggest Stanford students push the envelope beyond the Farm?

SB: Stanford is an incubator with dorms. I started two national programs here at Stanford. The first is called I-Corps, which commercializes science from the National Science Foundation. Next, we started Hacking for Defense, and that same year, I started Hacking for Diplomacy, while my co-instructors started Hacking for Climate and Hacking for Education.

The common thread, from the student’s perspective, is a search for a mission, whether that’s defense, diplomacy, climate, nonprofits, NGOs, or something else entirely. What these programs offer students is something they can feel, consciously or unconsciously, that they’re in service to. And here’s the word service again.

Even though I’m proud of my companies, I’m most proud of my children. Number two is my students. You get to watch their careers unfold. Many of them are CEOs, some of them are generals now.

And there’s Elon Musk! I ran the only company he ever worked for. I had no idea until I read his biography by Ashlee Vance. It said he worked at a video game company in San Francisco when I was the CEO of Rocket Science Games. I called my COO, and he said, Oh yeah, you used to yell at that kid, he was the intern.

I’ve had enough time here to watch the careers of my students unfold, and I’ve made a couple of dents in innovation and entrepreneurship. If someone remembers, it might be a footnote.

What I can tell you is that I cannot imagine getting paid to do this. Stanford has some of the best and brightest in the world. I teach elsewhere, and there’s nothing quite like Stanford students. It’s not just the horsepower, it’s the drive, the ambition, the vision, the commitment. And honestly, I learn more from my students than I think I give them.

JM: To come full circle on service, what’s the kindest thing someone has done for you?

SB: The kindest thing that ever happened to me was having three genuinely game-changing mentors. Gordon Bell, the first head of engineering at Digital Equipment Corporation, taught me what to think about. My co-founder Ben Wegbreit taught me how to think. And Rob Van Naarden taught me how to communicate and tell stories.

What I didn’t understand at the time was that they actually saw something in me I couldn’t yet see in myself. That’s ultimately why mentorship is different from coaching. It’s unconsciously a two-way street.

There’s a moment, somewhere in your late twenties or early thirties, when you’re most receptive to that kind of influence. And then something bittersweet happens: you realize the student has passed the master. It’s like watching your kids walk for the first time, or watching them leave home. I remember the exact moment I knew more than Gordon. It felt like – oh no. Now it’s my turn.

Most people are good at pattern recognition. Very few extract wisdom. When you find those people, those are the ones you want to learn from.

Stanford has an extraordinary concentration of that wisdom. These aren’t just smart people. A good chunk of them can tell you not only what the pattern is, but why the pattern exists. That’s rare. And that’s what makes this place great.