Table of Contents

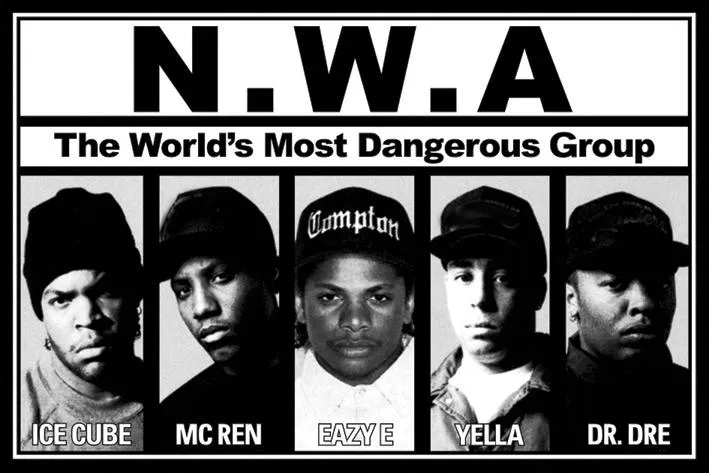

In late April, Professor Rose Salseda of the art history department gave a guest lecture in CSRE 196C: “Introduction to Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.” In that lecture, she said the word “n*gga” when quoting the lyrics to N.W.A.’s “F*ck tha Police.” About a week later, Salseda also typed the word “N*ggaz” when writing out the full name of N.W.A. in a discussion post for her own course ARTHIST 291: “Riot!: Visualizing Civil Unrest in the 20th and 21st Centuries.”

As a result, the Undergraduate Senate proposed a resolution to “Support Ethnic Studies Student Demands and Condemn Classroom Racism and Anti-Blackness.” The authors described the incident as “racial violence,” condemned Salsesda for “anti-Blackness,” and made a host of demands.

The suggestion that this incident constituted an act of “racial violence” is absolutely absurd. The word was being used in an academic context without the intention of aggression. The authors of the resolution even said that they bear the “emotional burden and labor of voicing their concerns.” This is not the rhetoric of an injured party, but rather an overly dramatic and self-congratulatory speech, attacking someone who has been an ally to the black community.

They also demand that students be “compensated for their labor and time via a paid internship or part-time employment.” If this truly is about an incident that the authors believe to be wrong, why monetize it? Shouldn’t the act of reporting be enough? Further, why must Professors Jimenez and Kim, the instructors of CSRE 196C where Salseda was a guest lecturer, also participate in “cultural humility training?” Imagine being punished for something you did not say. Seemingly, the authors want professors to be subject to the often capricious and quick-tempered whims of students.

On top of all of this, the resolution requests accommodations “for students who feel the need to drop this course due to the harm this incident caused to their wellbeing.” Hearing one thing that makes you uncomfortable should not afford the right to drop an entire course. Despite repeated claims of victimhood, making a list of onerous and inane demands at one of the only universities wealthy enough to fulfill them is truly the right of a privileged few.

In fact, Salseda was right to use the word in an educational context; she is a scholar of black art and music. Needless to say, it is obvious Salseda wasn’t using these words in a racist or aggressive manner. Yet somehow, the authors concluded that quoting an N.W.A. lyric was an act of “racial violence.”

When quoting sources in an educational context, a non-black person should be able to use the words “n*gga” or “n*gger.” When approaching sensitive topics, it is always better to confront rather than evade them. Education suffers when teachers become increasingly unwilling to say what they believe due to the impetuous bullying of students.

Censorship causes content to lose its meaning. The purpose of education is to make you think, and sometimes that means being uncomfortable. However, according to the authors’ demands, that purpose must be rote memorization or the continuous regurgitation and affirmation of uniform thought.

When you stifle academic freedom, you not only restrain reasonable discourse but sanitize history. What is the purpose of studying a highly redacted version of N.W.A’s “F*ck tha Police,” or any other text for that matter? What would discussions of the Civil Rights Movement or slavery look like with half of the material taken out?

Dancing around sensitive topics in no way begets deep thought. If Stanford wants to maintain its position as a leading center of intellectual discourse, uncomfortable history must be confronted, not silenced.