Table of Contents

“Die Luft der Freiheit weht,” translated as “The Winds of Freedom Blow,” sits boldly on Stanford University’s insignia as its guiding motto. Yet in the past several years, Stanford has become notoriously intertwined with academic censorship and the suppression of free speech. To adjust our sails correctly, we must first understand where and how we went wrong.

In 2020, many of the COVID-19 pandemic’s controversies took center stage at Stanford and tested the University’s purported principles of academic freedom and free expression. Almost every major censorious institution during the pandemic—from Big Tech companies like Twitter and Facebook to the federal government—was connected to Stanford in one way or another. But Stanford’s rocky relationship with academic freedom goes back long before the pandemic. In fact, it begins at the very founding of this university.

In the late 19th century during the American Progressive Era, Stanford’s first president, David Starr Jordan, hired Edward Ross, a young, vocal professor of sociology. Jordan described him as “head and shoulders above other men in his field.” Like his boss, Ross was an outspoken racist, known especially for his anti-Asian xenophobia that was popular among America’s working class. It was his bold progressive stances on immigration and the regulation of industry, however, that clashed with Stanford’s founder.

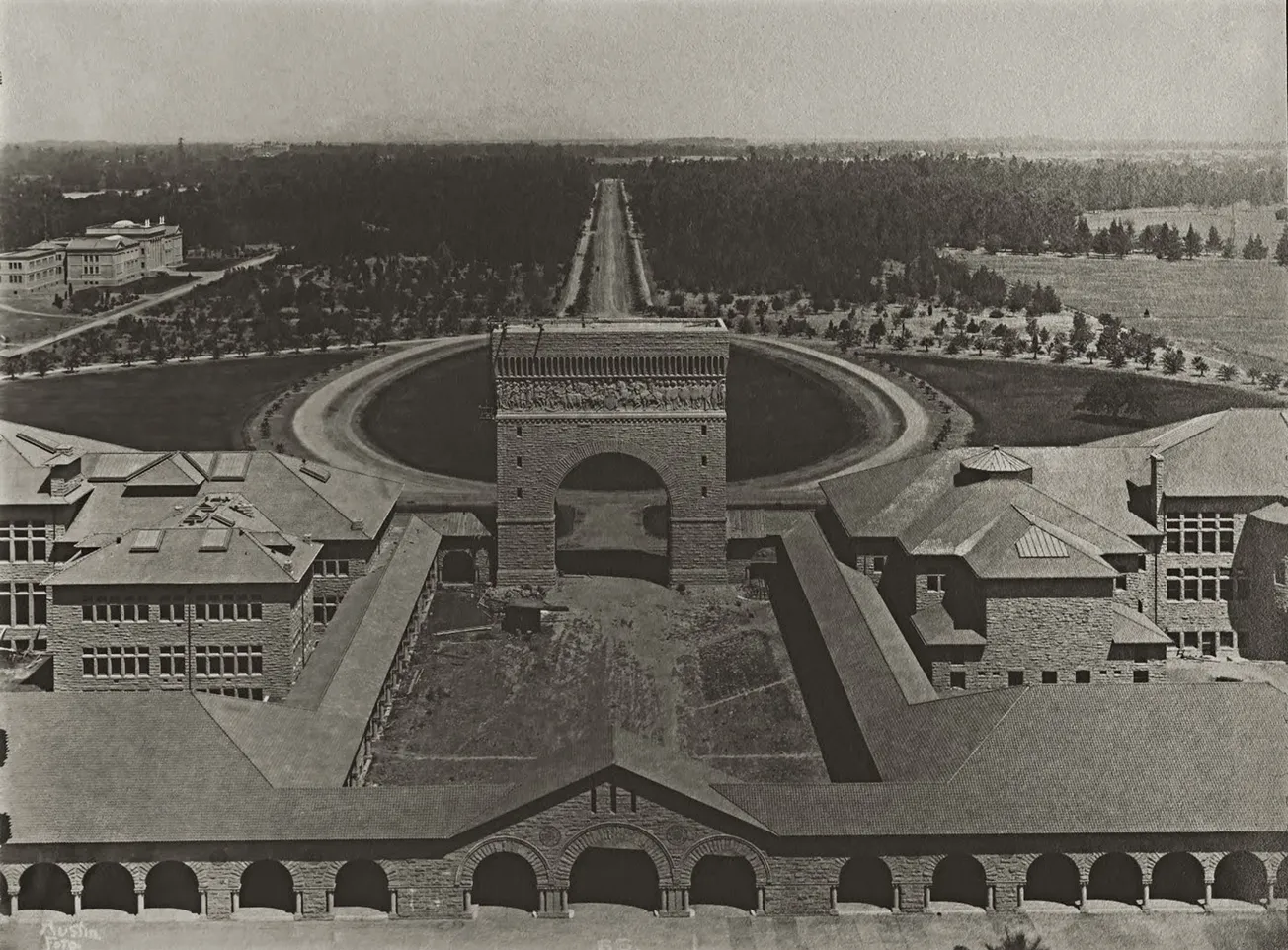

When Stanford opened its doors to its first “Pioneer Class” in 1891, Jane and Leland Stanford held total control over the University, and this control was left entirely to Jane after her husband’s passing. It turned out that Mrs. Stanford’s vested interests in the railroad industry could not be separated from her role as a university leader, however. Professor Ross’s outspoken criticism of Asian immigration—which western railroads relied upon for labor—and support for extensive regulation was a threat to her business and reputation.

In November of 1900, Professor Ross was forced out of the University at the demand of Jane Stanford, and his resignation initiated a stunning chain of events at Stanford and across the country. While seen as a villain by a few on campus, he quickly emerged as an American hero to the working class and supporters of academic freedom alike. As one op-ed in the Oakland Enquirer proclaimed, “When it is known that science in a university is under bonds to prejudice or dogmatism, the usefulness of that university is at an end and its further existence is without reason.”

Following Ross’s dismissal, he received overwhelming support from workers, unions, pastors, politicians, and fellow academics. Throughout the country, newspapers discussed the case of Edward Ross at Stanford, decrying the incident as a threat to science itself. On campus, one of Stanford’s leading faculty members, history professor George Howard, came to the defense of Ross and, in turn, was also dismissed. One by one, several other Stanford faculty members resigned, and some of these faculty members, distraught from the censorship on Stanford’s campus, went on to initiate the practice of academic tenure as we know it today.

The case at Stanford had struck America with fear of an academic institution that could censor and control science at its own whims, and the debacle left the University in a dire crisis just years after its founding.

Fast forward over sixty years to when Bruce Franklin, like Ross, was a young and outspoken Stanford professor in the 1960s and early 70s. Franklin, an English professor, had developed into a Marxist during his time on campus, as well as a vocal activist against American involvement in the Vietnam War. He vocalized his beliefs on Stanford’s fraught campus, rallying students who would overrun campus buildings and shout down opposing speakers.

The first of Bruce Franklin’s incidents began when Henry Cabot Lodge, the former Ambassador to Vietnam, came to speak at Stanford in 1971. Professor Franklin was a part of the audience and heckled Lodge alongside others in the crowd. Lodge was shouted down and prevented from speaking, and in response, Stanford’s President Richard Lyman suspended Franklin from his job for one quarter.

Later, when students had barricaded themselves in a building, Franklin encouraged and condoned the protesters while condemning the police presence, which had over one hundred riot police confront the protestors. The Vietnam-era tension on Stanford’s campus further spiraled out of control and a later violent conflict following another Franklin speech resulted in student injuries. President Lyman once again blamed Franklin for inciting the unruly protest and fired him from the University. His departure was the first time—and so far, the only time—that a fully tenured faculty member at Stanford was fired.

A few years after Franklin’s dismissal, a Stanford PhD student of anthropology named Steven Mosher had an exclusive opportunity to travel to China. On his expedition to the Guangdong province, Mosher documented something striking: forced abortions and sterilizations thrust upon women living under the Chinese government and its now notorious one-child policy. The struggles of modern rural China were revealed to the Western populace for the first time by his report, bringing to light a damning revelation of the living standards in Communist-controlled China. Unsurprisingly, Mosher’s work agitated the ruling Chinese Communist Party, which was already apprehensive about outside scholarship and research in its country.

The Chinese government leveraged Mosher’s case to pressure American institutions to comply with stringent demands when sending researchers to its country. Eventually, the committee of eleven Stanford anthropology faculty members, possibly as a result of this Chinese pressure, unanimously voted to expel Mosher, stating that he was guilty of “illegal and seriously unethical conduct.” His research methods and style were deemed dubious and said to jeopardize the integrity of his research, but Mosher maintained that Stanford expelled him to placate China.

In 1992, Stanford President Gerhard Casper stated that “A university's freedom must be first of all the freedom that we take mostly for granted, though the humanists had to fight for it and others must still do battle for it even today: the pursuit of knowledge free from constraints as to sources and fields.” He spoke of a glorious principle that this institution seeks to embody.

Yet as one can see, academic freedom at Stanford has had a much longer and more problematic history at Stanford than many assume. The past few years at Stanford have been an exceptionally dark era—and may have irreversibly tainted our school’s reputation—but the University’s struggle to uphold academic freedom is nothing new.

Portions of this article were reproduced from ECON 139D at Stanford University.