Table of Contents

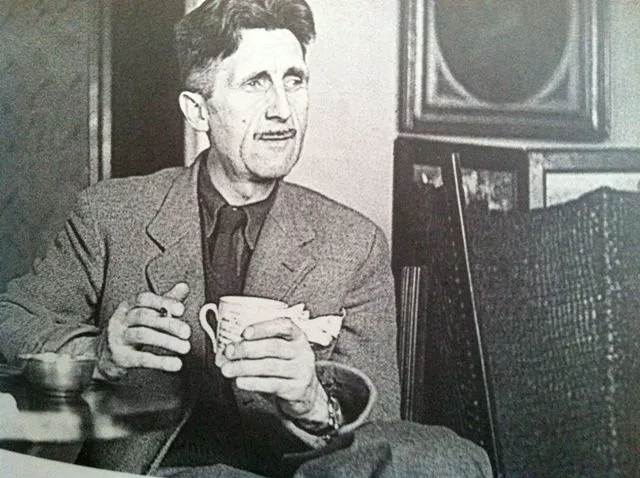

Though I am hesitant to trespass on ground already covered so authoritatively by the inimitable George Orwell, during the course of a handful of recent conversations about the relative merits of coffee and tea, my attention has been drawn to some worrying facts. Not only is tea unfairly denigrated by Stanford coffee-drinkers, but there abound considerable misconceptions on campus about its correct preparation. To address this shocking inadequacy, I humbly offer my guide to a satisfactory cup of tea, and end with a call to arms for better tea-drinking habits to be observed here on campus.

Begin by pouring a splash of boiling water into the teapot. Swish it around and pour it out. Pour more water over the leaves and set a timer: five minutes for a strong cup of black tea, three for green tea. Letting the leaves sit too long makes for an astringent cup and masks the subtler flavors. Water should be poured at boiling for black tea, and at slightly under boiling for green tea. Green tea leaves, if of good enough quality, should be able to be re-used to brew another pot of tea after a first steeping. Black tea leaves, on the other hand, should be pitched out after the first steeping.

It is very important to use a teapot or other vessel to brew the tea separate from the vessel from which you will drink the tea. There are all sorts of reasons not to brew the tea in the same vessel from which you drink it. One is purely aesthetic: the correct and most pleasing way to drink tea is poured from a teapot. There are practical reasons as well. On the one hand, you may have brewed a relatively small cup of tea, and used an entire teabag to do so, in which case you have not only used the leaves inefficiently, but are liable to end up with a bitter and overly strong cup. Oin the other, you may be drinking from a vessel holding a large enough volume of tea that it remains undrinkably hot for half an hour and then almost immediately after becoming drinkable, becomes unpleasantly lukewarm.

Pouring out tea into a smaller cup serves to aerate and mix the tea, as well as to cool it down. For those of you who happen to own these faddish double-walled hot-and-cold water bottles, I recommend filling one with tea before walking to class and bringing along a paper cup to pour the tea into. It’s a decent way to smuggle caffeine into the libraries, though you didn’t hear that from me.

Milk is only permissible in strong black teas and is really only proper if you happen to be in the U.K. at the time. Green tea should never mix with milk; the matcha latte is thus an abomination against nature. Sugar is right out. Iced tea should be made very strong, as the process of cooling it down with ice usually dilutes it, and because flavors generally come through less well in cold beverages.

Coffee has always reminded me of mud in a cup. It’s terrifically earthy; espresso grounds even resemble dirt. The taste remains in the mouth, stains the teeth, lingers on the breath. Tea, on the other hand, is a more ethereal beverage, gentler on the teeth and breath as well as on one’s mood. Tea cannot, of course, be counted on to jolt the drinker into action or wakefulness as coffee is often relied on to do. It serves rather to heighten the focus, and provokes neither the jitters nor the crash that coffee does.

Large quantities of tea are always preferable to small quantities. Make tea by the liter, not by the cup. Not only does this result in a more efficient use of the leaves, but it allows the drinker to sip constantly during a whole morning’s work, during an entire afternoon class, et cetera. The attention-heightening effects of tea are best experienced by drinking it almost constantly for long periods of time.

It is worth investing in high quality tea. The tea that proliferates in large quantities in the U.K., despite that country’s reputation for tea-drinking, is of a very low quality. Even the United States’ major mass-produced tea, Lipton, is preferable to Twinings or Yorkshire Tea. A box of sachets or loose-leaf tea, however, will produce a much better cup than these packets of tea-flavored dust. Tazo and Stash make the best of the American teabag teas, though the former is often guilty of promulgating outlandish and unappetizing blends. Harney & Sons is a trustworthy company for sachets and loose-leaf; Teavana is equally dependable if rather twee. The best American company is Steven Smith Teamaker, who also run two very high-quality tea rooms in Portland, if one happens to pass through that fine town.* A general observation is that far fewer people drink tea in America than in Britain, but those who do generally take the enterprise more seriously.

In the realm of black tea, Assam makes a brash, strong, coppery cup, while Darjeeling is lighter and more subtle. Earl Grey, usually a blend of teas scented with bergamot oil from Calabria, is arguably the finest of the flavored black teas. Japanese green teas are lush, fresh, and grassy (sencha); or else hearty and malty (hojicha, genmaicha). Oolong teas, somewhere between black and green tea, possess some of the most interesting flavor profiles. Some taste like butter; others are fruity like white wine.

If I am allowed one complaint about Stanford it is that nowhere that I know of on campus serves tea in a teapot. This is a great crime that should not be allowed to continue. One has to trek all the way to the Coupa Café at the golf course to obtain tea as it should be served. Even there, the atmosphere is far too formal and bourgeois to permit any actual schoolwork to be done. I get nasty looks from waiters whenever I pull out my laptop. Is a pot of tea and a space to work too much to ask? Spreading the word about the proper preparation and consumption of the world’s finest caffeinated beverage is the only recourse I can conceive of to prompt Stanford’s cafés into action on this most essential of topics. I am willing to pledge loyalty to whichever café acts first, and to defend the winning establishment in the presses — as indeed I have done in the past.

*(One also cannot go wrong with French teamaker Mariage Frères -Ed.)