Table of Contents

Hanno Lustig is the Mizuho Financial Group Professor of Finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business and a Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Working at the intersection of macroeconomics and finance, Lustig has established himself as a leading voice on international finance, asset pricing, and fiscal policy, with particular emphasis on the valuation of government debt and the sustainability of sovereign obligations. He earned his PhD from Stanford in 2002 and has been on the faculty since 2015.

This conversation explores the sustainability of U.S. debt and what happens when the world’s safest asset isn’t safe.

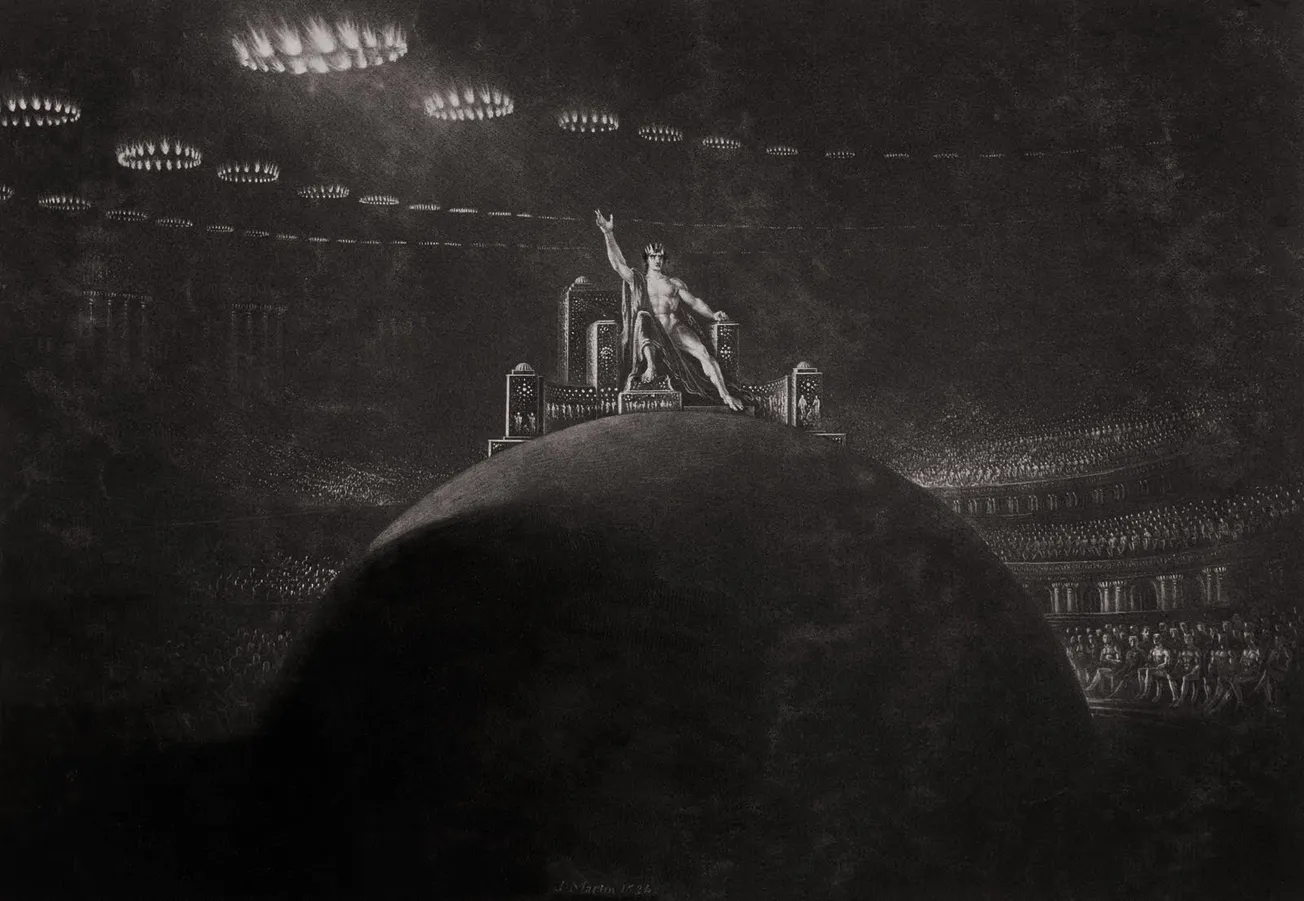

Professor Lustig encourages readers to look to history, such as 20th-century Britain’s loss of dominance, to understand how the past can predict the future and why America’s “exorbitant privilege” has limits. He examines the emerging alternatives: Bitcoin’s fundamental constraints, stablecoins’ paradoxical role in extending dollar hegemony, and why central banks are suddenly accumulating gold. Throughout, Lustig reflects on what it means to challenge consensus thinking in the world’s deepest financial market.

Jack Murawczyk: Where do you most sharply disagree with the consensus view on financial markets, the U.S. economy, or the sustainability of public debt?

Hanno Lustig: I started thinking about the valuation of government debt by looking at the valuation of all Treasuries.

What do we have to believe to get to a number like $38 trillion?

You must believe there will be a huge fiscal correction, because ultimately the value of debt should be backed by future primary government surpluses. When you do the numbers, you realize that either bond investors are pricing in a huge fiscal correction that seems impossible, or Treasuries are significantly overpriced.

That’s a provocative statement because it’s such a huge, deep, liquid market. It’s hard for people to believe that Treasuries could be overpriced in a systemic, dramatic way. That’s where I’ve parted ways with the consensus mainstream view. The key difference is how I approach this with my co-authors. As financial economists, we take risk and return very seriously and think carefully about how to price something that is ultimately just a claim to future government surpluses. Our conclusion is that these Treasuries look overpriced; they’re super expensive.

That point in and of itself has been made by others. But what we do differently is, instead of comparing a 10-year Treasury to a 10-year corporate bond, we look at the whole portfolio of Treasuries and see if we can make sense of the valuation of that entire portfolio. We apply the same tools we would use to value a stock, using a discounted cash flow model just like an investment banking analyst would.

JM: For decades, the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” has been the ultimate global monopoly, providing the world’s safe assets. Are we witnessing the endgame of that monopoly? What happens when the safe asset provider is no longer safe?

HL: This is an important question because one of the reasons Treasury valuation in the US seems detached from underlying macro fundamentals is exactly this: exorbitant privilege. Foreign investors are willing to keep absorbing the supply of Treasuries without looking too hard at the underlying fiscal fundamentals.

There are signs that suggest we’ve exhausted that privilege. If we do a careful apples-to-apples comparison of Treasuries to corporate bonds, you used to think, boy, these Treasuries look really expensive. That’s not true anymore.

JM: Microsoft bonds now offer a lower yield than equivalent treasuries!

HL: One thing that is particularly relevant is the correlation between Treasuries and stocks. The correlation of return on all Treasuries with the return on all stocks used to be reliably negative, resulting in a negative beta asset. If you were having a rough day in the equity market, you could rely on your treasury investments to provide a little bit of insurance. That’s no longer the case.

If I were a congressman on Capitol Hill, this would tell me we’d better get our fiscal house in order because it looks like we’ll be dealing with different market conditions, we’ll be borrowing at higher interest rates, and we may have trouble finding enough buyers for all the debt that we want to issue.

JM: Your work compares the US’s post-WWII experience to the UK’s pre-WWI dominance. What lessons from the UK’s exorbitant privilege lost are most relevant for the U.S. today, especially regarding the long-term sustainability of its debt?

HL: In the 19th century, the UK was roughly in the position of the US today. They were the world’s safe asset supplier, London was the financial center of the world, and the pound was viewed as a reserve currency. In fact, Alexander Hamilton noticed this early on when he observed gilt yields. He understood there was a huge benefit to being the world’s safe asset supplier. As a result, Hamilton built an institutional framework and a debt market around it that would allow the US to achieve a similar status.

In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, the UK issued substantial debt: the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 150% in the early part of the century. During the First World War, the UK was forced to tap capital markets heavily to finance the war and support its allies. They ended up in serious fiscal trouble. After the Second World War, the US took over as the safe asset supplier, partly through Bretton Woods re-engineering the international financial system.

This illustrates a difficult reality: when governments face wars (or pandemics), they shift part of the taxpayer burden onto bondholders by allowing inflation to take off. There’s a price to doing this. Bondholders will remember and price that in, especially at the long end of the yield curve. That could mean higher borrowing costs in the long run, because investors now realize that when bad things happen, they’ll bear part of the cost.

JM: The axe forgets, but the tree remembers.

Moving on, it seems likely that the next safe haven won’t necessarily be a sovereign currency. Crypto advocates argue Bitcoin is “digital gold.” Meanwhile, stablecoin volumes now rival some sovereign currencies in transaction volume. Are these technologies accelerating the dollar’s decline, or paradoxically, are USD-backed stablecoins actually extending American monetary dominance?

HL: It’s early days, so it’s hard to tell what the ultimate impact will be.

Bitcoin faces a fundamental problem: if it became truly successful, it would dramatically impair governments’ ability to tax their citizens. If the volume got big enough, there would be a crackdown. Governments would be forced to do something because it creates non-traceable wealth; they wouldn’t be able to tax capital gains. That’s why I struggle to see a world where Bitcoin dramatically pays off.

Stablecoins are a different story. They’re very promising for making the international payment system more efficient. Are they a threat to the dollar as a reserve currency? Not really. What they’re likely to do, because these are essentially money market mutual funds that invest in Treasuries as collateral, is increase demand for Treasuries, especially at the short end of the yield curve. In that sense, they might actually help.

The odd thing about stablecoins as currently engineered is that issuers are essentially running money market mutual funds but not paying interest to holders.

JM: A fantastic business for them.

HL: But it’s not a great business for the investor.

JM: For the first time since 1996, foreign central banks’ gold reserves have overtaken their U.S. Treasury holdings. Is gold accumulation by China, Russia, and others a genuine hedge against dollar debasement, a geopolitical signal, or merely expensive theater? In a world of CBDCs and USDCs, does gold’s 5,000-year run as money still matter?

HL: It’s a signal that many market participants are questioning whether Treasuries are still safe assets. The US is close to exhausting its exorbitant privilege, and market participants, including central banks, are searching for alternatives. Treasuries used to have negative or zero beta. Now they’re not so sure. Gold comes to mind as an alternative with negative beta.

The interesting thing is that as a result of this increased demand for gold, it now appears to have positive beta in the short run. Equity valuations and the stock market are being pushed up, and gold has appreciated at the same time.

JM: Interestingly, the fear narrative (gold) and faith narrative (AI) are concurrent.

HL: One thing that helps the US is that there’s a beauty contest aspect to this. Yes, US fiscal fundamentals are pretty dismal, but many of the obvious alternatives are in worse shape.

In Europe, the demographic pressures are greater and GDP growth rates are lower. Even though the Europeans run smaller deficits, their economy is growing at a much lower level, so they’re not a great alternative.

Moving on to China, there are governance issues in that it's not a democratically elected government. But there’s a much bigger issue beyond governance: What is the total debt burden in China? It’s harder to do the math because you have to look not just at the central government but also at the local government and debt issued by state-owned enterprises. If you did, you’d realize that China is not in great shape when it comes to debt, either; it’s just that there’s no transparency. The prognosis isn’t great. Add in China’s aging population with a shrinking working-age population, and the outlook deteriorates further.

So what could save the US for now is simply that it’s a beauty contest based on relative positioning. The one thing that could change that is AI. But the growth effects are still uncertain. It’s very hard to see right now how AI will effectively create the sustained growth the US needs.

JM: You earned your PhD here in 2002 and now hold a chaired professorship. What’s the single biggest change you’ve seen in the university since your own days as a grad student?

HL: Obviously, Stanford was a great university when I first got here in 1997, but if I compare it to where we are now, it had a provincial feel to it. Whereas now, you have the sense that you’re at one of the top universities in the country. When I started my academic career, it sometimes felt like Stanford was a nice place to be for a number of reasons, but it felt like you were on the periphery. The center of gravity in economics, at least in academics, was Cambridge and Chicago. I think that’s changed. It feels different now.

JM: If you could have dinner with any historical figure who faced a fiscal crisis (Hamilton, Keynes, Volcker, or someone else), who would it be, and what would you ask them?

HL: I’d love to have a dinner conversation with Milton Friedman.

Friedman is probably one of the greatest social scientists of the 20th century. In his writings, he warned about the dangers of unfunded, pay-as-you-go pension systems. He intuitively understood that in a democracy, this creates a problem: the people who vote are typically older and have very different interests from those who can’t vote yet, or haven’t been born, who will eventually have to pay for these unfunded liabilities.

I'd like to ask him how we should try to get out of that and hear his thoughts on it.

My first year as an assistant professor, the highlight was his 80th birthday party at the University of Chicago. They celebrated by organizing a conference with sessions dedicated to each of his main contributions: the Permanent Income Hypothesis, his analysis of the Great Depression with Anna Schwartz, and monetarism.

After each session, they would ask him if he wanted to add something, and he would get up with no prepared remarks and speak in perfectly composed paragraphs. He was super impressive.

JM: What book most changed how you see the world?

HL: I’m a voracious reader, and I read lots of different things, novels in addition to nonfiction. One of my favorite books is Freedom From Fear by David Kennedy, about the Great Depression and its aftermath.

JM: That's a classic. Kennedy is brilliant.

HL: It was one of the books my thesis advisor, Tom Sargent, told me to read, and I learned a lot from it. One thing I’ve noticed about my generation of economists is that we generally know less about history than our predecessors did. People like Bob Lucas and Tom Sargent, distinguished macroeconomists, had that grasp of history.

JM: And Joel Mokyr, also.

HL: Yeah, part historian, part economist. Those are aspects of our discipline that we’ve undervalued – this idea of looking at history to understand the challenges we face today. We talked earlier about exorbitant privilege. That’s a great example, because it’s hard to understand through quantitative calibrated models. But you can look at history: the UK in the 19th century up until the First World War, or before that, the history of the Dutch Republic. Both countries, when they were the world’s safe asset supplier, borrowed heavily and eventually ended up in serious trouble. That’s a cautionary tale.

JM: To conclude, what’s the kindest thing that someone’s done for you?

HL: When you’re an academic, you realize that if you have even a moderate degree of success, you owe so much to your advisors. In my case, I was lucky enough to have Bob Hall and Tom Sargent as my academic advisors here.

Tom Sargent, in particular, was an extraordinary advisor because he had a deep understanding of what made people tick. He would look at you and understand whether he needed to push you or be very careful, depending on how close to the edge you were. He had that instinctive knowledge. In addition to being an extraordinary academic and a great social scientist, which he still is to this day, he was a gifted advisor because he had a deep understanding of how to approach graduate students.

Somewhere on the Internet, there’s a graph of all the people Tom Sargent has advised, his genealogical tree. It’s quite impressive. In fact, it’s hard to find a macroeconomist who isn't in some way connected to him.

JM: The Kevin Bacon of economics.

HL: Yeah, when you get a little bit older, you think, boy, I was lucky to have people like him willing to advise me. I’m tremendously grateful for that.

This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity, length, and grammar.