Table of Contents

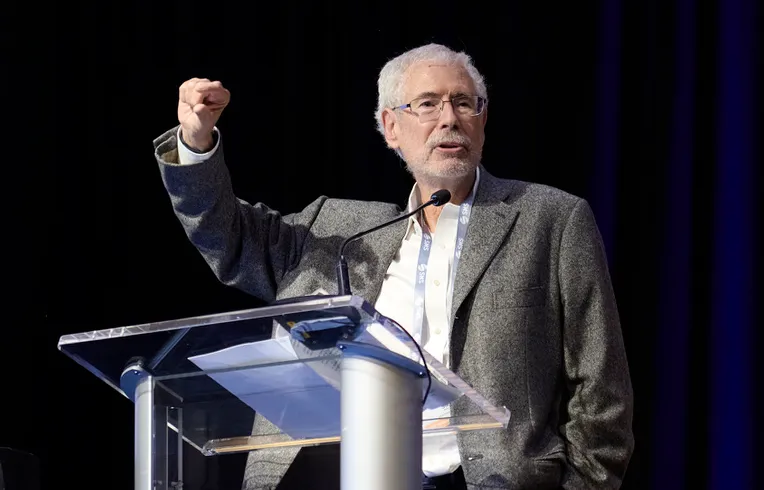

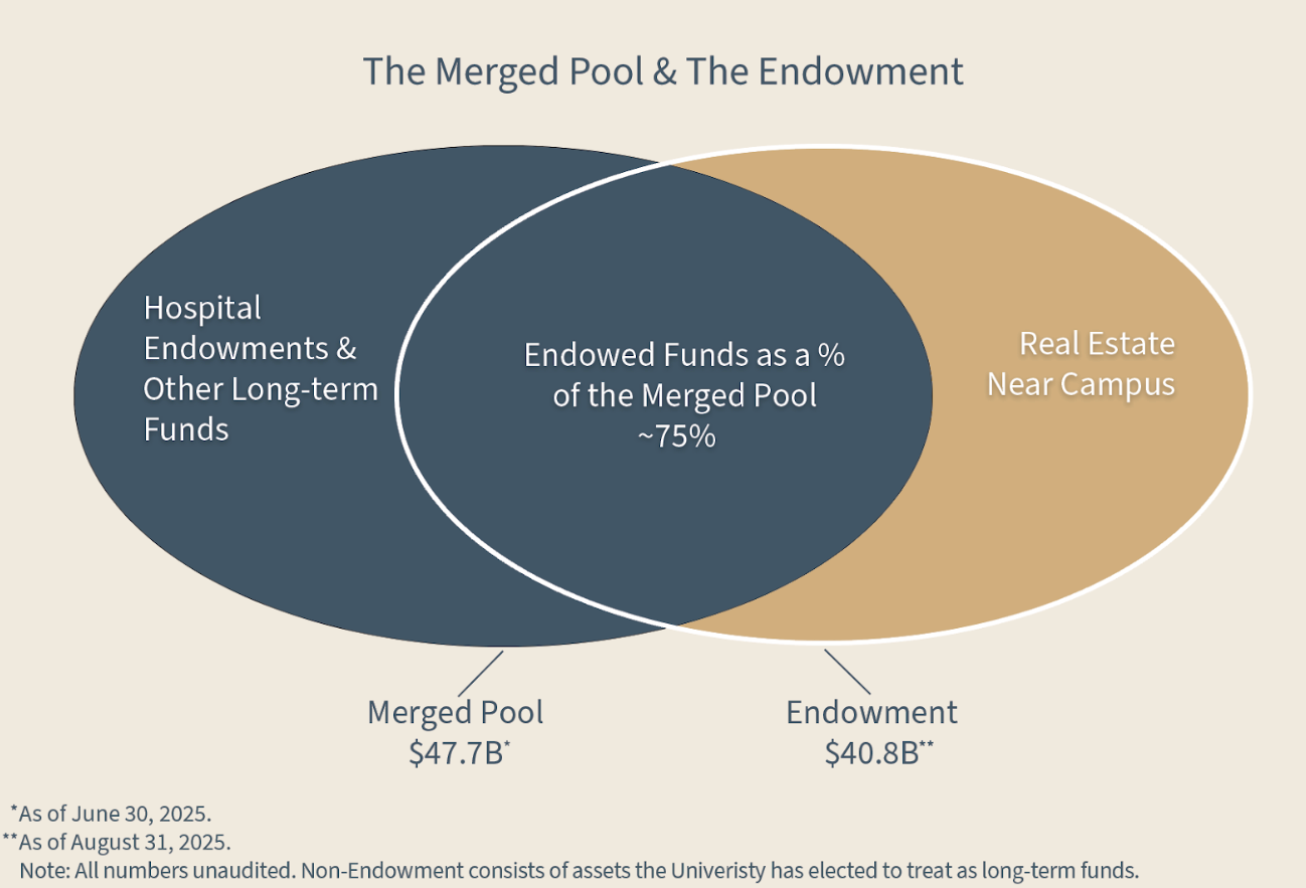

Robert Wallace is the Chief Executive Officer of the Stanford Management Company (SMC), where he oversees Stanford’s $47.7 billion investment portfolio. Wallace took the helm in 2015 after serving as CEO of Alta Advisers, a London-based private investment firm. His investing career began at the Yale Investments Office under the legendary David Swensen, where Wallace learned the endowment model that would come to define his approach at Stanford. Wallace graduated summa cum laude from Yale with a degree in economics – though not before spending 16 years as a professional ballet dancer, eventually retiring from the stage at 32 to pursue higher education.

The following conversation explores the principles of long-term investment management and disciplined contrarianism in an era of tremendous change, opportunity, and complexity.

Wallace reflects on the lessons of rebalancing the portfolio amidst collapsing markets during March 2020, the challenge of scaling alternative strategies at $50 billion, and why the rise of passive investing may paradoxically create opportunities for fundamental investors. He draws on wisdom from his mentor David Swensen’s emphasis on first-principles thinking, the importance of relationships as well as rigorous quantitative work, and the courage required to stand alone when your analysis demands it.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Jack Murawczyk: You’ve had a remarkable and unconventional career. You were a professional ballet dancer for 16 years, then graduated summa cum laude with a degree in economics from Yale. That’s not a typical path to running a $48 billion endowment. How do these seemingly disparate worlds connect and interrelate?

Robert Wallace: I danced professionally from age 17 to 32, and then went to Yale as a freshman at 32. I pursued both ballet and investing because I found them fascinating, challenging, and intense. They were areas where I could give my full intellectual, emotional, and physical self and get a lot back. Both require deep immersion and constant personal growth.

They do share one fundamental property: if you’re trying to become a world-class ballet dancer, it takes a really long time. Every day, you go into the studio and work on technique over and over again, and that only pays off many years later.

Running a large endowment like Stanford’s is similar. Every day you come in, you’re working hard, finding opportunities, diligencing those opportunities. It’s a nose-to-the-grindstone approach, and the decisions you make and the work you do today pay off five or ten years from now. That long-term perspective and patience for the payback is something that classical ballet and endowment management share.

JM: You joined SMC in 2015 and have successfully led it through zero-interest-rate policy, a pandemic, historic inflation, and the fastest rate-hiking cycle in memory. What is the single most important thing you’ve learned from navigating decades of market cycles?

RW: The most important thing in managing an endowment portfolio through a variety of market environments is discipline. As an institutional investor, you create a policy asset allocation framework for your portfolio, which outlines how we want to design our portfolio in terms of risk, return, and liquidity to support the academic mission over the next 10 years.

When market movements take your portfolio away from your desired positioning, the disciplined thing to do is to rebalance back to those policy weights you specified, assuming you still think you specified them correctly. That requires a contrarian move.

For instance, in March 2020, COVID hit and global equity markets fell 30% in three weeks. That obviously moved our asset allocation all over the place inside the Stanford endowment. We were now very underweight equities because they had fallen 30%, and overweight absolute return assets that maintained their value. Our reaction was to sell the things that had held their value, and to buy the things that had fallen to bring them up to their policy weight.

It was a swift, contrarian move. In the last days of March 2020, we were sending our partners a lot of money – partners that had just lost us a lot of money, while taking money from our partners in areas of the portfolio that had made us money. Most people were running for the exits, thinking the pandemic was going to destroy the financial system. But the disciplined thing to do when there are moves that large is to rebalance back to the allocation structure that is going to make Stanford successful over the next decade.

And so we did that. That’s a lesson that institutional investors must keep in mind during periods of volatility.

JM: Where do you most sharply disagree with the consensus view on financial markets today? How is SMC positioned to capitalize on that contrarian view?

RW: I’ll give you a few thoughts on the current environment. First, AI is evolving rapidly, and there’s nothing more important today than to pay attention to how to play offense and defense in the world of AI.

Powerful companies are being built and growing unusually fast, much faster than anything we saw in the internet boom of the late 90s. These companies are going from zero to 900 million annual recurring revenue (ARR) in 18 months. But that revenue is not necessarily sticky. You have to worry: can it be competed with? How strong are the competitive moats?

Another thing we’re paying close attention to is the valuation of risk assets, particularly in the United States. Both equity and credit look quite fully valued.

JM: The Schiller P/E Ratio hit 40 today!

RW: Yeah, there’s a lot of leverage in the system, and not all of it is obvious. The combination of high valuation and significant amounts of leverage should make people think about the downside. It’s one of the reasons we run a diversified portfolio. You don’t want all your eggs in one basket. It’s part of our discipline to maintain a diversified posture at all times. And that’s certainly important right now.

JM: You have access to some of the best investors and technology entrepreneurs in the world through Stanford’s network and capital base. What have you learned from them that has subsequently informed your allocation and investment decisions?

RW: There’s no better source of information than our partners and what they see happening in the world. On AI, for example, it’s crucial to engage with our venture partners, but it's also important to talk to owners of mature businesses that are trying to develop AI strategies to keep up with or defend against new entrants. We’re in close contact every single day with our partners. There’s probably no better source of information.

JM: We’re now facing a collision of huge correlated risks that aren’t in the standard David Swensen model, like the sustainability of sovereign debt, the disruptive force of AI, and geopolitical concerns. Has the underlying endowment model been forced to adapt to these conditions?

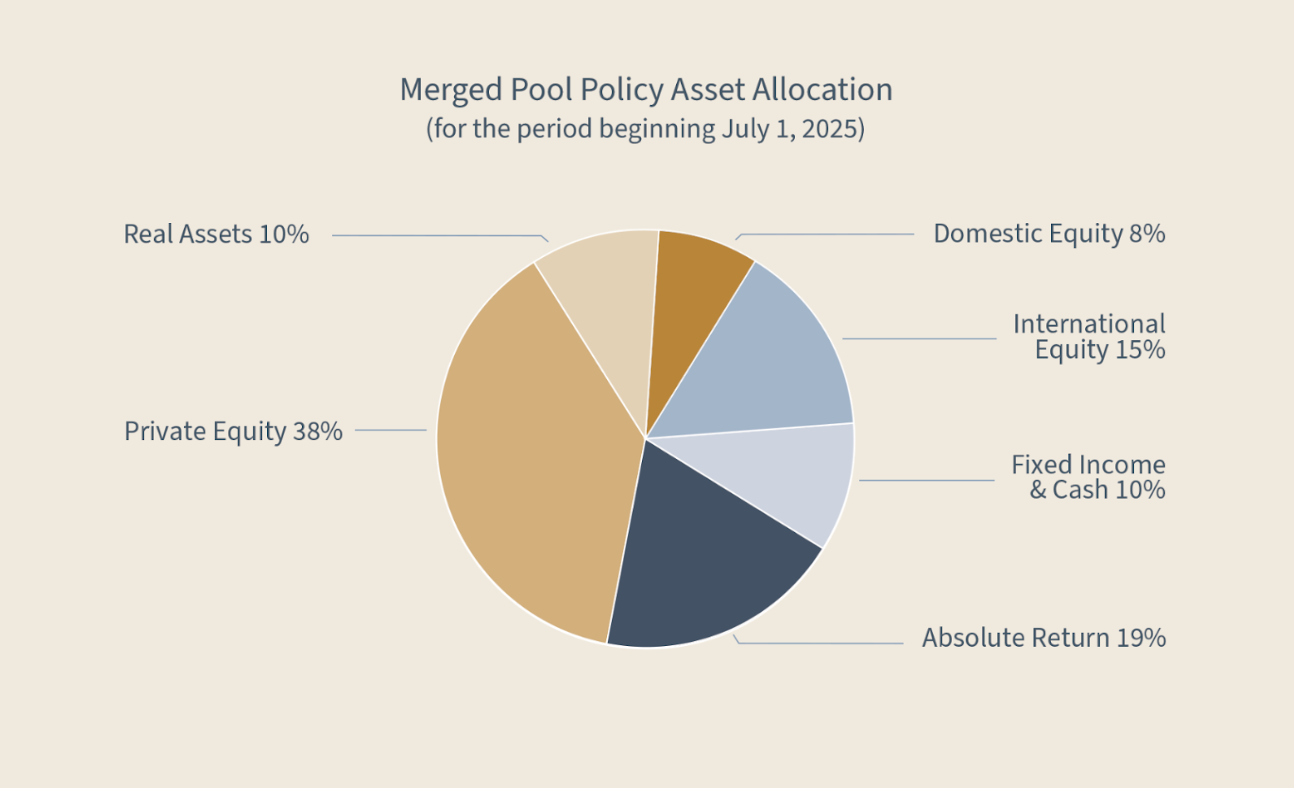

RW: The principles of the endowment model that David developed are pretty simple. Have an equity bias in your portfolio – around 70% equity investments, which is roughly where we are at Stanford, while the other 30% is for diversification. You need an equity bias because you need to earn a 6% real return (after inflation) if you plan to disburse 5% to the school’s operating budget and hope to preserve purchasing power so the endowment can be equally supportive to all future generations of students and scholars.

That other 30% needs to be genuinely diversifying. Those are the two core principles of the Yale Model. I don’t think that has changed at all. Those principles are likely to never change.

One more thing Swensen was known for was investment in alternative asset classes. He was clear that the ability to invest in venture capital, leveraged buyouts, and absolute return strategies – where there’s a high degree of dispersion between successful and unsuccessful investors – puts a premium on your ability to pick the right partners.

You're now putting great emphasis on execution. If you think you can drive differentiated performance, you’d better be sure you’re right. You’d better be in the top quartile or the top decile (in the case of early-stage venture) because everything below that doesn’t look good net of fees. That was true 20 years ago, and it’s still true today.

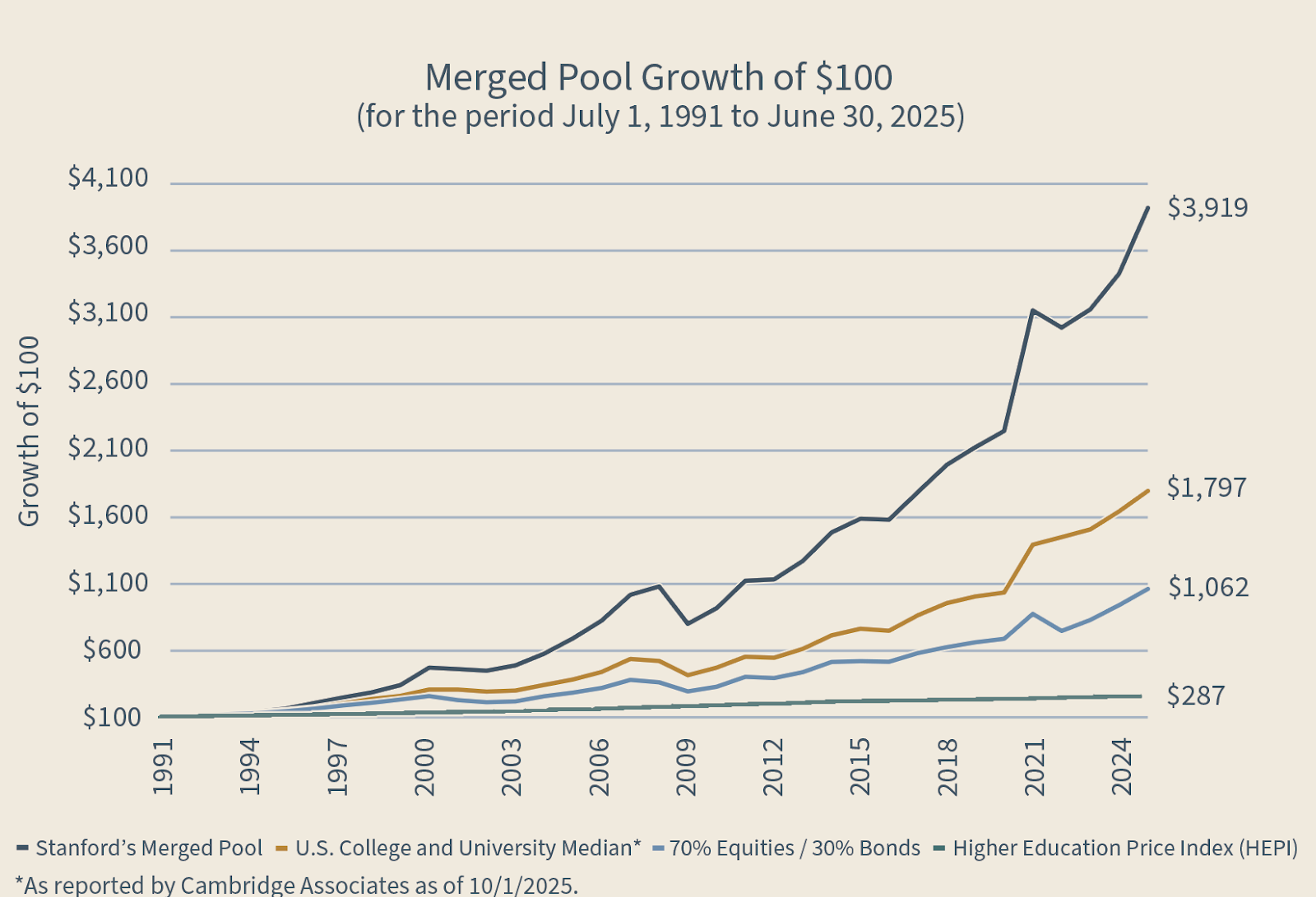

One thing that is different for Stanford is that now we’re much bigger. We’re approaching $50 billion in Stanford’s Merged Pool, and managing that is a lot harder than when we were at $25 billion, when I joined Stanford 10 years ago. When David wrote his seminal book on endowment management, for example, Yale was at $5 billion. It’s hard to scale some of these alternative strategies. The execution challenge gets much harder at $50 billion than it was at $10 billion.

JM: Sequoia’s Roelof Botha had a great clip with venture capitalist Jack Altman on the fundamental impossibility of scaling early-stage venture as an asset class, given the talent constraint.

You can invite any investor – dead or alive – to dinner. Who are they, and what's the one question you’d want to ask them?

RW: It would be hard for me not to say David Swensen, who died about five years ago. Not only was he a brilliant investor, he was a close friend of mine. The chance to have one more dinner with David would be hard to turn down.

JM: What did you learn from him? What did you find most valuable in that mentorship?

RW: So many lessons. The importance of a rigorous analytical framework, contrarianism, and discipline. The investment work we do may look quantitative on the surface, but the core is people-oriented. You’re building relationships with incredibly talented people in different parts of the investment world and around the globe – identifying them, understanding what they’re doing, and building the right type of trustful, open, supportive relationship. That’s mission-critical if you want to do the type of investing we do at Stanford.

Also, the importance of thinking from first principles, which dovetails with contrarianism. You don’t want to be a blind follower in investment markets. You want to be able to reason from fundamental premises using rigor and data. That may take you to an unusual set of places where you don’t see a lot of other investors. If you’ve done your work the right way, that’s actually an advantage. He certainly taught me that.

JM: Do you find that the rise of passive investing, retail, and momentum trading makes it more challenging to do that? Does it just take longer? What are the impacts you see from that?

RW: It’s an open question exactly what the rise of passive investment has done. You see it most pronounced in the US equity market. Ultimately, in the long run, it gives the remaining active investors an advantage. If there are fewer people paying attention to fundamentals, there should be more mispricings. It just may take longer for the mispricings to close.

JM: The Grossman-Stiglitz Paradox!

RW: A bigger issue for fundamental investors is what the high-frequency, short-term trading, quantitative algorithmic investors are doing to the market. They generally don’t care much about what the fundamentals are on a five-year view. They care about the immediate news flow: what’s the momentum, what’s happening in the next few minutes. That leads to some strange things happening in public markets. That should be an advantage over a long period, but it can lead to pronounced periods where the fundamentals don’t matter.

JM: Excluding Swensen’s Pioneering Portfolio Management, what book most changed how you see the world?

RW: I do remember when I was a teenager reading a biography of Winston Churchill. I’ve now read several Churchill biographies, my favorite of which was Sir Martin Gilbert’s biography of Churchill, which is long but beautifully done.

But the one I started with had on the inside flap a beautiful quote from John F. Kennedy, who was himself quoting Teddy Roosevelt. The quote goes:

“The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who at best, if he wins, knows the thrills of high achievement, and, if he fails, at least fails daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.”

That quote has stuck with me through my whole life, and it’s something that Churchill clearly lived his life by. I thought that’s a great statement for somebody to keep in mind as they live their life. It’s certainly helped me in both of my careers, to push myself and dare to try.

JM: The ultimate first principle!

To conclude, what’s the kindest thing that someone’s done for you?

RW: That’s an easy one: my wife marrying me. That’s the kindest thing that anyone’s ever done for me!