Table of Contents

At the southwestern edge of Stanford University lies what was once its crowning jewel: Lake Lagunita, an artificial lake that seasonally emerges with California’s winter rains. In its heyday, the lake was as fundamental to Stanford as Main Quad or Hoover Tower. By filling Lake Lag with diverted water, the University created a canvas for Stanford’s freeminded and enterprising students to experiment, play, and manifest. Lagunita was the site of countless sailing expeditions, moonlit first dates, water skiing, and even the construction of artificial islands. The lake provided a medium for students to develop the agency and initiative characteristic of the Stanford man, fostering the pirate spirit that makes Stanford an incubator of innovation.

But beginning in the 1990s, government agencies and environmental activists pressured the University to curtail the lake, seeking to protect two federally-threatened species—the steelhead trout and the California tiger salamander.

In 2001, Stanford ceased filling the lake to recreational levels; in 2013, Stanford signed an agreement with the federal government that legally mandated a half-filled Lake Lag. For a quarter-century now, students have been prohibited from using it; most winters, it sits too shallow for boating or swimming anyway.

For most Stanford students, the lakebed remains a morassy relic from a long-gone era—before the University waged its “War on Social Life” and planned “Winter Wellness” sessions. Pining for the lake’s return, the Stanford student consoles himself by ascribing the demise of Lagunita to some solemn duty to protect the salamander or trout.

An investigation by the Review, however, dismantles that fictional narrative. Practically, Stanford would now be able to fully fill the lake to recreational levels without harming either threatened species.

The true culprit is a single federal agreement that renders the lake legally impossible to fill—for now. The Review has compiled the first comprehensive history of the lake, uncovering the bureaucratic forces that consigned it to a vestigial swampland, and charts a path towards refilling it.

The Birth and Life of Lake Lagunita

In 1876, Leland Stanford went on a spending spree. The railroad magnate acquired thousands of acres of farmland in the Santa Clara Valley to create the Palo Alto Stock Farm, a state-of-the-art horse breeding facility.

Stanford, however, needed a way to irrigate field crops like oats and alfalfa through the Valley’s dry summers. Thus, Stanford’s engineers fashioned an earthen dam to transform a small swale west of the main barn into a permanent reservoir of water. Lake Lagunita, the “little lake,” was born.

When Leland and Jane Stanford donated their Palo Alto property to their newly founded Stanford University, this irrigation reservoir came with the land. Built to water crops, Lake Lag would become a fixture of campus life.

Lake Lagunita was always a seasonal, managed lake. Each winter, the University would fill the lake for students’ recreation, using the Lagunita Diversion Dam to divert water from San Francisquito Creek. For a century, the lake would run full from Christmas Break to Commencement.

Lake Lag hosted hallmarks of the Stanford student experience. The Big Game Bonfire, the Water Carnival, impromptu canoe races, jet skiing—Lagunita became a playground where students would venture and experiment, exemplifying the University’s Wild West ethos.

At the turn of the 20th century, the specter of environmentalism trained its sights on the former vernal pool. In 1992, the California tiger salamander was rediscovered in the San Francisco Peninsula, and Lake Lag was one of its breeding grounds. The lake students loved wouldn’t survive the next decade.

Draining the Lake: From Recreation to Regulatory Oblivion

The salamander’s rediscovery triggered a cascade of restrictions. Thought extinct on the Peninsula since the 1970s, the species attracted immediate environmentalist concern. In 1993, the Stanford administration canceled the Big Game bonfire, held for decades every November when the lakebed lay dry, out of fear that hibernating salamanders would be incinerated.

Regulatory scrutiny followed. A year later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the California tiger salamander as a “Category 1 candidate species,” signaling its intent to declare the species protected under the Endangered Species Act. Meanwhile, salamanders migrating into Lake Lag were being crushed by cars on Junipero Serra Boulevard.

Mounting salamander roadkill triggered the first legal regulations on Lake Lagunita. In 1998, Stanford University signed the California Tiger Salamander Management Agreement with county, state, and federal environmental agencies. This agreement enacted positive measures, creating amphibian tunnels under Junipero Serra Boulevard to reduce salamander mortality, but it also reclassified the lake. No longer a recreational reservoir, Lagunita was becoming a wetland to be conserved.

The salamanders weren’t the only problem. Just as the lake itself fell under regulatory control, so too did its main water source, San Francisquito Creek. In 1997, the Central California steelhead trout, which inhabited the creek, was listed as federally threatened. Suddenly, Stanford’s historic water rights fell under Endangered Species Act restrictions, making it much harder to fill the lake for recreation.

The University began bending under the accumulating regulatory pressure of salamander and trout. In 2000, it signed the Santa Clara County General Use Permit, granting a conservation easement over Lake Lag to protect tiger salamander habitat. This imposed a few operational restrictions, but marked a formal surrender of the lake’s recreational purpose.

The final blow came in 2001. Stanford ceased filling Lake Lag to recreational levels after it was on alert that diverting water from San Francisquito Creek could trigger federal enforcement action over the trout. Instead, the University filled the lake to 3-5 feet, the minimum depth needed for salamander breeding, and drew water primarily from the Felt Reservoir to avoid burdening the trout’s water supply.

Student use of the Lake evaporated. Though a subset of rebellious students still take to the lake’s shores when it fills during exceptionally wet years, the university maintains that recreation is a thing of the past. The era of recreational Lake Lag was over. It became a swampy vestige of University history.

We Can Refill the Lake

In March of 2013, as required by the Endangered Species Act, a Habitat Conservation Plan was finally signed between Stanford University and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The agreement codified and superseded the 2000s-era semiofficial prohibitions on filling Lake Lag. “Categorically defin[ing]” the lake’s use until 2063, it prohibits filling the lake with treated water or for any recreational purpose, mandating that Lake Lag be filled to only 3-5 feet for the salamanders.

The Habitat Conservation Plan is what now keeps Lake Lag empty. (While California’s CEQA law might create additional hurdles, recent reforms have streamlined its processes, making CEQA far more surmountable than a federal ban on fully filling Lagunita.)

The great irony is that the Plan’s onerous environmental regulations protect neither the salamander nor the trout.

Additional water in Lake Lag poses no threat to tiger salamanders’ survival, nor does the lake’s recreational use. In fact, the Habitat Conservation Plan itself recognized that Lake Lag’s recreational use “facilitated California tiger salamander … persistence at Stanford.” Furthermore, Stanford has stated that “tiger salamanders require water and contrary to a widespread rumor are not the reason why the reservoir is not filled to former recreational levels.”

Current restrictions are now tied to the trout. The conservation plan justified limiting Lake Lag’s water levels by noting that “the practice of withdrawing water from San Francisquito Creek and diverting it to Lagunita … can adversely affect biological resources (including steelhead [trout]).”

This justification is obsolete. Stanford couldn’t fill Lagunita with water from San Francisquito Creek even if it wanted to; the University dismantled the Lagunita Diversion Dam on the creek after a 2013 lawsuit brought by environmentalist groups.

Instead, Stanford would fill Lagunita by using the Felt Reservoir, the Searsville Dam, and runoff from campus—leaving both trout and salamander intact. In fact, torrential rains filled Lake Lag in both the winters of 2023 and 2024, proving that a full Lagunita is no environmental catastrophe, but instead a boon to student life.

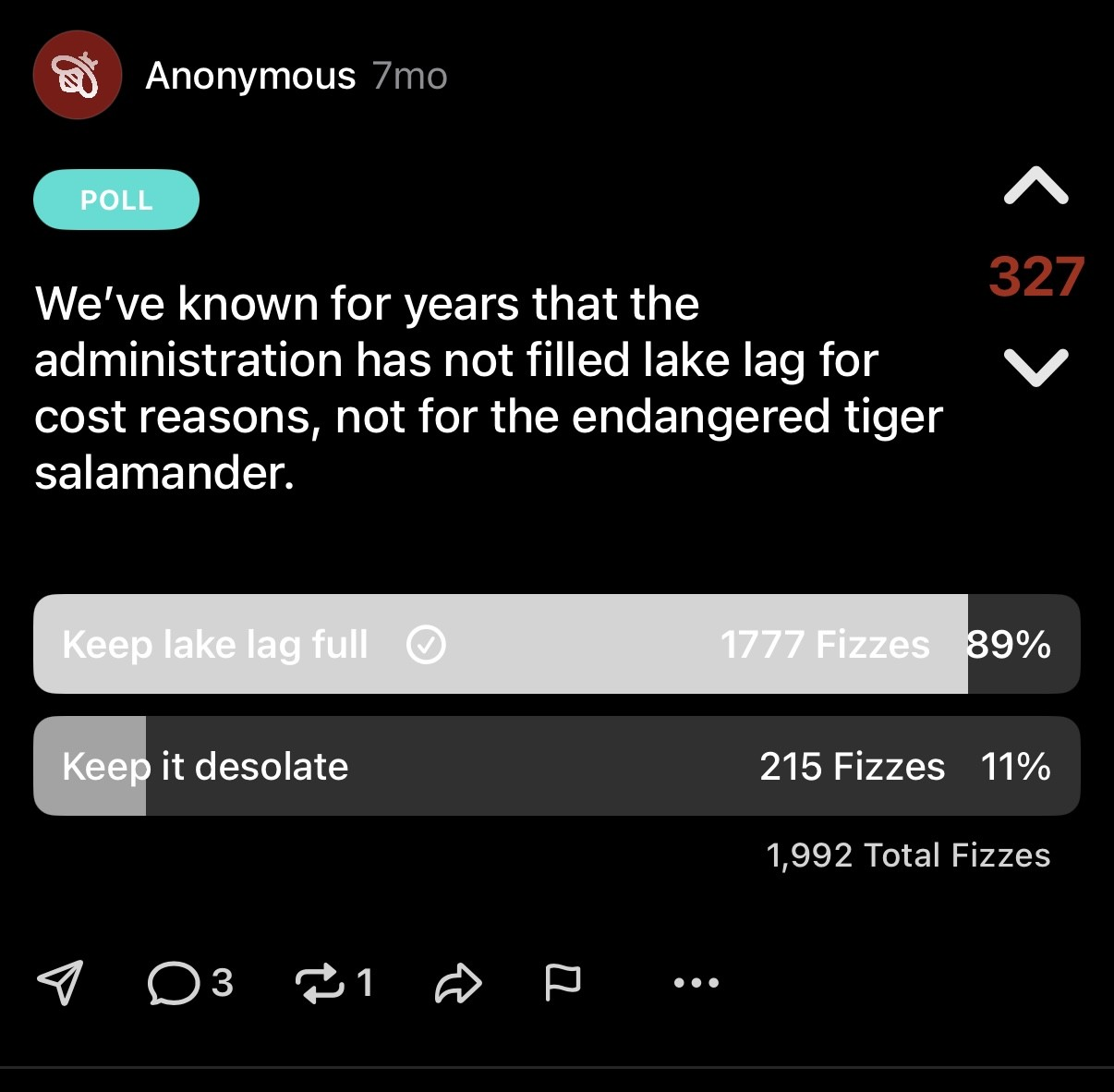

Refilling the lake is deeply popular among Stanfordians. Students regularly take to Fizz (a Stanford-exclusive, anonymous social media app) to advocate for Lake Lagunita, receiving thousands of upvotes:

Surely, if unshackled from regulatory constraints, University administrators would do so.

***

In sum, Stanford students lost Lagunita under the now-obsolete guise of protecting tiger salamanders and steelhead trout, but Stanford can refill the lake without harming either species.

What stands in our way is the Habitat Conservation Plan. Fortunately, it’s entirely under the purview of the federal government. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Brian Nesvik could refill the lake at the stroke of a pen; given his penchant for rationalizing environmental regulations, he might well do so.

And he should. Lake Lagunita bestowed priceless joy, memories, and agency upon generations of Stanford students. By ending an overreach of perhaps well-meaning but crippling environmentalism, refilling the Lake would strengthen the soul of Stanford. Not only does a dry Lagunita rob Stanford of its Western Spiritedness and thymos, but first and foremost, it is an attack on fun and the student body.

Authors’ Note: This history pieces together hundreds of pages of often fragmented and difficult-to-find sources. Environmental regulations are notoriously byzantine; we have done our best to ensure accuracy and welcome further insights.