Table of Contents

It has been almost five years since the Faculty Senate approved the COLLEGE program in May 2020, and I believe I speak for most Stanford students when I say it’s time to go back to the drawing board.

The COLLEGE program (a loose abbreviation of Civic, Liberal, and Global Education) is the latest in a long series of attempts to design a first-year general education curriculum for students at Stanford University. In an address to the inaugural 2021-2022 cohort of COLLEGE instructors, former president Marc Tessier-Lavigne described the goals of the new program, which would provide first-year students with “the opportunity to think about ethics and citizenship within a rigorous academic context, the opportunity to think critically about their own views and preconceptions, and the opportunity to deepen their thinking about our society and our world.”

Unfortunately, the degree to which COLLEGE accomplishes any of these goals has been offset by the subtle but pervasive damage it has done to the intellectual climate on campus. Owing to a disjointed curriculum and an embarrassing failure to incentivize student engagement, COLLEGE doesn’t come close to its ideal as a “shared intellectual experience.” Instead, it suggests to first-year students that at Stanford—and in life—you don’t have to work hard, or even do the readings. You just have to show up.

Indeed, the educators behind the COLLEGE program have misunderstood something fundamental about the psychology of college students. The contract grading scheme (pass-fail in Stanford speak) forces COLLEGE instructors to pass the vast majority of students, whether or not they complete a single page of assigned reading. This policy is demonstrative of the COLLEGE team’s misprioritization of students’ mental health over engagement and learning, which gives first-year students the impression that Stanford humanities courses are not worth their time, effort, or respect. Needless to say, students have no incentive to invest their valuable time in a course that doesn’t reward them for hard work but gives them an A for attendance.

But Professor Dan Edelstein, the inaugural director of the COLLEGE program, seems to be in denial about the lack of student engagement with coursework. “When more than 1,000 first-year students are grappling with the same ideas, reading the same texts, writing the same assignments and engaging in the same activities at once,” he wrote in 2022, “the walls of the classroom start to dissolve. Debates about what it means to disagree in good faith carry on in the residences themselves; discussions of the good life continue over dinner.”

This sounds nice in theory, but alas, Professor Edelstein is living in the same dream world as former President Tessier-Lavigne. In an anonymous survey, I asked my classmates in COLLEGE 101: “Did you complete the assigned reading for today?” I was pleasantly surprised that 30% of my classmates had done the reading. On the other hand, Edelstein is correct that the COLLEGE program has given first-year students something to discuss over dinner—how much we dislike it.

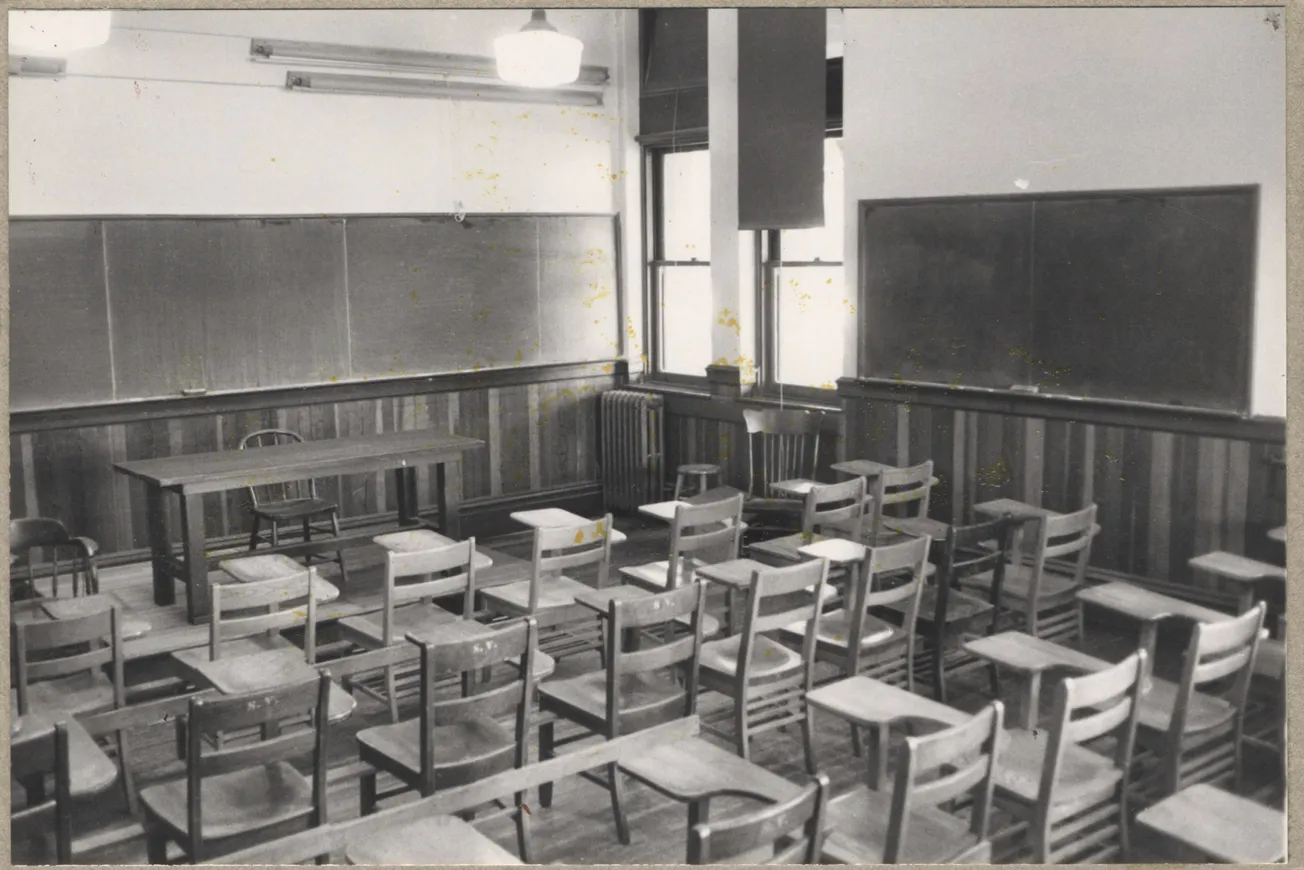

The feeling among my fellow freshmen is that the COLLEGE program amounts to, at best, a waste of time and, at worst, a direct contributor to the climate of anti-intellectualism on campus. The curriculum is discontinuous and, at times, just plain nonsensical—why, for example, are we assigned a brief excerpt from Plato's Allegory of the Cave one week and the entirety of Open, a ghost-written celebrity memoir about a tennis player, the next? Seemingly, the readings were selected to check boxes: one from the right, four from the left, and racial and gender diversity throughout. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with diversity unless it comes at the expense of substance. In my view, asking the esteemed faculty of this university to lead freshmen in discussions on a miscellany of magazine articles, blog posts, and news stories on broad themes like “Education and the Good Life” and “Citizenship in the 21st Century” is an insult not only to their intelligence but to ours.

When I’ve expressed these frustrations to faculty members, some have commiserated, expressing their disappointment in the curriculum and reminiscing about the intellectualism of years past. Others have pushed back, arguing that the curriculum achieves its goal of “leveling the playing field” for first-year students. Certainly, freshmen come to Stanford from a wide range of backgrounds and with a variety of life experiences. But ideally, these experiences don’t include intellectual frailty or the inability to rise to an academic challenge.

Some of my peers have rejected my criticism of COLLEGE, arguing that my frustration with the program should instead be directed at the student body and, by extension, the admissions department. In their view, our generation’s best and brightest aren’t interested in reading books—they just want to write code and solve math problems—and this is why the level of engagement in COLLEGE seminars is so dismal.

However, this view fails to hold the university responsible for the decay of its intellectual climate. Stanford students are capable and ambitious and are naturally drawn to a challenge—to deny this is to deny that there are any students at any university who possess these traits. The university, not the students, bears the responsibility of setting the tone when students arrive on campus. If COLLEGE is Stanford’s attempt to introduce freshmen to the humanities, it’s no wonder Stanford students favor STEM majors, which they know will hold them to a higher standard than class participation and a weekly discussion post.

My message to the university is this:

Please do not coddle us in the hope of coaxing us out of our shells. Coddling has the opposite effect on the minds of high achievers: It saps our motivation and causes us to reserve our energy for activities that demand excellence from us. Stanford students are ready and eager for an intellectual challenge. We want to learn, and we aren’t afraid of homework—or of grades. We want to read books cover to cover like they used to do in the days of old. We want to write essays and receive detailed feedback on how our writing can be improved. We appreciate profound ideas no matter who they come from, and we are not offended by the prospect of reading two texts written by white males in a row. We want to imbibe the sophistication we admire so much in our professors, and we want to learn what they have to teach us. Above all, we don’t want to be told how valuable a liberal education can be, we want to experience its value first-hand. And if we can’t experience it first-hand at Stanford, I’m afraid there’s nowhere on planet Earth where we can.