Table of Contents

Last spring, we took CS 224R: Reinforcement Learning, one of the year’s most popular classes, taught by Professor Chelsea Finn. Her lab revolutionized modern AI, pioneering inventions like model-agnostic metalearning (which enables AI systems to learn new tasks from just a few examples) and DPO (a key algorithm behind instruction-following chatbots). Off her research, she raised $400 million for her robotics startup Physical Intelligence. We were eager to learn from one of AI’s key minds.

When we discovered that the only models allowed for our final projects, the Qwen models, came from China’s Alibaba, we were stunned. Here we were, in the heart of America’s AI effort, learning about AI on Chinese models.

This wasn’t Prof. Finn’s preference alone: other notable Stanford classes use Qwen models, as Chinese open-source models often surpass America’s in balancing cost and performance. (Unlike with closed-source ChatGPT, researchers can freely modify and experiment with open-source models.)

Americans first became aware of Chinese progress in AI in early 2025, when DeepSeek stormed onto the world stage. Investors panicked; NVIDIA stock plummeted. But the apocalypse never came: DeepSeek turned out to be slightly worse than other frontier models, not dramatically better. Within weeks, the narrative snapped back to comfortable assumptions: China can copy, but they can’t truly innovate.

Something far more significant is happening beneath the surface. Chinese AI’s real transformation is happening in their research ecosystem, through a surge of papers at top-tier AI conferences - work seen only by experts, but that will soon burst into products and capabilities that reshape the landscape.

Silicon Valley proceeds largely unaware. A good friend echoes conventional wisdom: China’s “strength is diffusion, without our innovation, their system fails.”

Under this logic, doesn’t it make sense to prioritize guarding American secrets above all else, since China cannot innovate independently? Isn’t it enough to just stop them from stealing what we’ve already built?

Not anymore.

Alarm about Chinese AI isn’t new. Headlines have warned of China’s rising AI paper counts and patent filings since the 2010s. But these papers were generally subpar, ignored by serious researchers, and the concern fizzled.

This time is different. Now, America’s best AI researchers look to China for cutting-edge work.

We first heard this from Jack*, a prominent researcher at an industry frontier AI lab. Many of the exciting new papers in RLHF—the hottest field driving AI performance breakthroughs—have been coming from China, he told us. We then chatted with other researcher friends at Stanford. All confirmed this shift; several brought it up unprompted.

Some will argue this doesn’t matter. After all, American frontier labs OpenAI and Anthropic still have state-of-the-art closed-source models that trounce open-source alternatives.

This misses the deeper threat: the talent pipeline. Every frontier AI lab recruits top researchers from universities, where they can identify skilled researchers with promising directions. As Tsinghua and Zhejiang now produce engineers on par with Stanford and MIT, those engineers will staff DeepSeek, autonomous drone manufacturers, and every other strategic Chinese AI company. America’s monopoly on top AI talent is breaking.

Stunningly, this shift happened entirely over the past four years.

In 2021, Hristo began his AI research journey in adversarial robustness. American researchers at Stanford, CMU, and MIT dominated the field, with some notable Swiss and British research, and essentially no papers from China.

In general, whatever Chinese AI papers were relevant—like the famous 2016 Resnet paper, which powers Tesla’s autopilot, or the 2021 SWIN transformer paper used in Philips’ medical imaging—came from Microsoft Research China, an American company’s outpost. Chinese universities, meanwhile, published systems papers or adapted American innovations for local use, as in the 2021 papers PanGu-α and Chinese BERT, where the authors “revisit the existing popular pre-trained language models and adjust them to the Chinese language.” They were diffusing, not innovating.

China’s AI ecosystem in 2025 would be unrecognizable compared to four years past. A team from Tsinghua University and ByteDance introduced visual autoregressive models, winning NeurIPS 2024’s best paper award. NeurIPS is arguably AI’s most prestigious conference, where Stanford and other top American universities compete to publish their greatest work. Tsinghua graduates also recently published Hierarchical Reasoning Models, widely lauded in Silicon Valley circles. These papers offer genuinely new approaches to unsolved problems, inspiring the future work of America’s top labs. Four years ago, this kind of innovation from China was inconceivable.

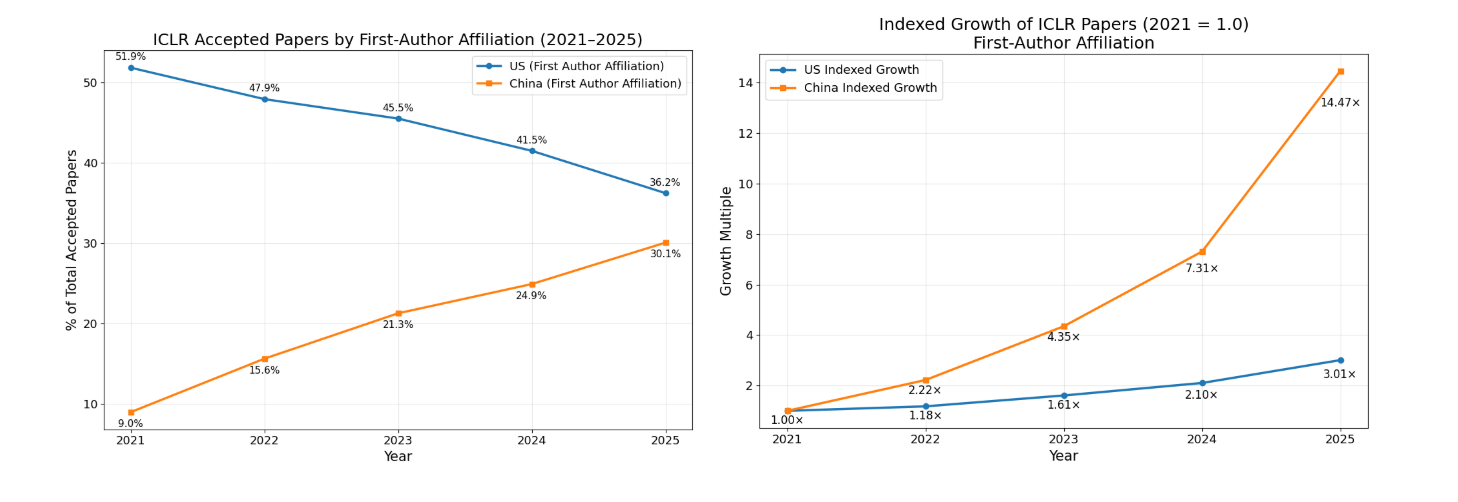

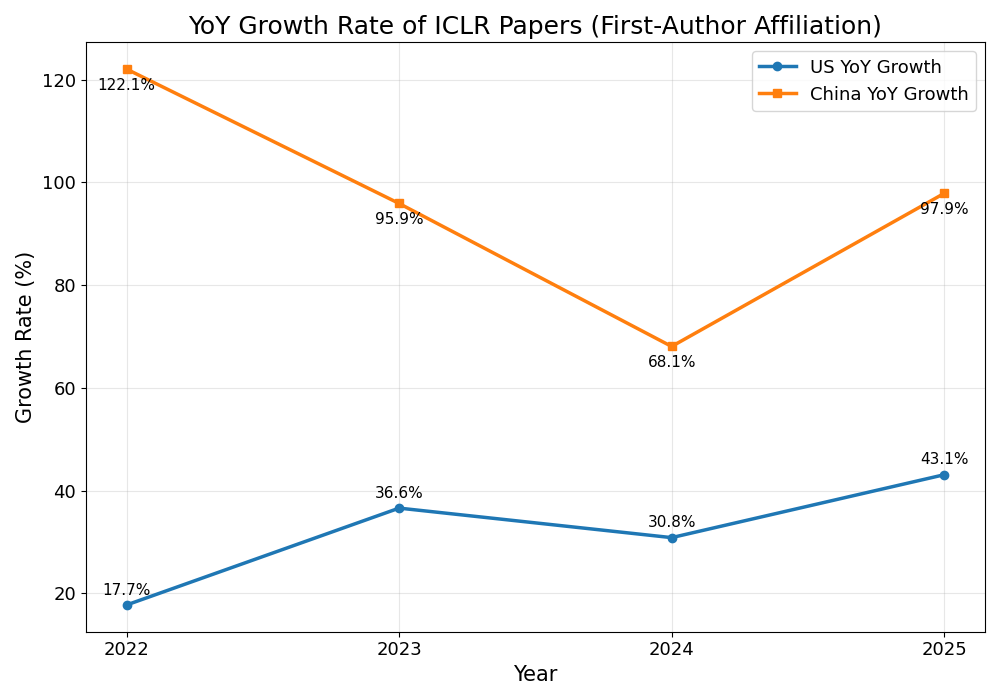

This shift from derivative work to genuine innovation shows up in the numbers. At ICLR, one of AI’s three most prestigious conferences, the share of Chinese papers has surged: outnumbered 5-to-1 by American papers in 2021, Chinese papers are almost equally numerous in 2025. The same pattern holds at NeurIPS and ICML, the other two top AI conferences.

These conferences are brutally selective. They require that papers make notable progress on crucial unsolved problems or introduce entirely new lines of thinking. They regularly reject even top Stanford researchers’ work; boilerplate papers do not make it through. China’s surge here represents a worrying shift in quality.

What happened?

First, China has deep technical talent. This is a society of engineers, with rigorous mathematical education from childhood. It is easier to teach AI research to an engineer than to a lawyer.

Second, China invested heavily in university-industry collaboration. When we talked with Kevin*, an international student who studied at a top Chinese university before coming to the US, we learned that Chinese universities and companies were closely sharing research and infrastructure. This is not the case at American universities. At Stanford, even though there is a university-wide computer cluster infrastructure, most PhD students end up writing a significant amount of overlapping toolkits to facilitate running their experiments.

Third, and most uncomfortable for American policymakers: we trained them. Many of China's leading AI researchers earned their PhDs at Stanford, MIT, and CMU. They learned from the same advisors, published in the same conferences, and absorbed the same research culture. An entire generation sharpened their talent at Microsoft Research China. Then they went to Shenzhen, bringing the tacit art of doing research with them.

The unfortunate reality is that Chinese AI will only surge faster in the near future. DeepSeek had a profound psychological impact on Chinese society; the CCP committed to investing significantly more money in AI. It has begun approaching AI with the same mindset and toolkit as its manufacturing industry, and we are already seeing new Chinese companies producing good models across a wide range of verticals. Given this, we predict that there will be more Chinese than American papers at ICLR 2026; for the first time, China will dominate a top AI conference.

If we learned anything from the current AI wars between American tech giants, it is that talent from the universities and the research labs is the key to innovation. Last year, Google paid an astonishing $2.7 billion to bring back the researcher Noam Shazeer, who left the company in 2021. Google didn’t buy any of his work, as they already own most of his research; they paid this amount of money to have Noam and his research skills themselves. This is not a one-off: the AI talent wars between frontier labs have featured multibillion-dollar buyoffs, surpassing Cristiano Ronaldo’s or Shohei Ohtani’s packages.

When Stanford students default to Chinese models, when robotics startups build on Chinese infrastructure, when the most exciting RLHF papers come from Chinese labs, the fundamental shift is clear: China's AI ecosystem no longer simply diffuses American ideas but innovates independently.

The last thing American policy should do is accelerate this shift by making it easier for talent to flow back to China. Yet that's exactly what current F1 visa rules accomplish, forcing Chinese PhD students to arrive with the understanding that they should return home after graduation. Every Chinese AI researcher who leaves America will go to Shenzhen to build the next DeepSeek instead of fueling American innovation. This won't protect America's AI lead; it will help erode it.

We should be concerned, and we should be strategic. The era of assuming American AI dominance is over. The decade ahead depends on the choices we make now.

Names marked with asterisks are pseudonyms to protect sources who spoke under conditions of confidentiality.