Table of Contents

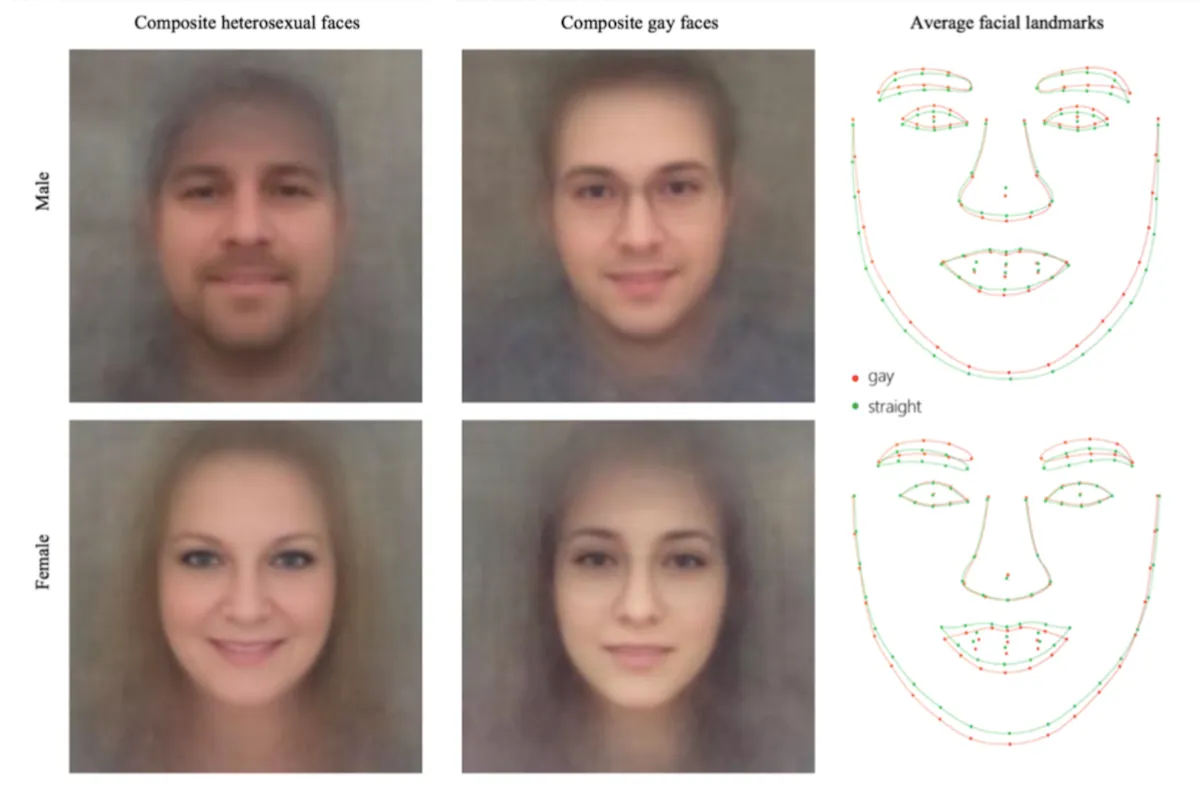

A dismaying but tragically predictable wave of vigilantism roiled Stanford recently when professors Michael Kosinski and Yilun Wang dared to conduct some uncomfortable research. They found that a computer algorithm could infer a person’s sexuality based on a facial photograph. The study used neural networks to extract features from over 300,000 images downloaded from a popular dating site with public profiles. When shown a single facial image, the algorithm accurately distinguished between homoesexual and heterosexual men and women 81% and 74% of the time, respectively. When fed five images per person, these levels of accuracy rose to 91% and 83%.

In the aftermath of the study’s publication, controversy and criticism were abundant. A professor at Oberlin College labeled the study “the algorithmic equivalent of a 13-year-old bully.” LGBTQ+ advocacy groups condemned the study as “junk science,” arguing that the algorithm could be used as a weapon against homosexual individuals. In a joint statement, GLAAD and the Human Rights Campaign smeared the research as “dangerous” and deemed it flawed and incorrect. The study was criticized for excluding segments of the LGBTQ community, including people of color and transgender individuals, amongst others. Kosinski and Wang called these statements “knee-jerk” reactions that failed to comprehend the science behind the work.

The debate revolving around this research, though thoughtful, is dismally narrow. It focuses too much on ethics and fails to consider the broader implications of the study. The arguments above gloss over the question of why research is produced in the first place and ignore the implications of the AI revolution for academia at large.

The purpose of academic research is to generate new knowledge in a meaningful way. The fact that this is a remotely controversial suggestion says something depressing about the current academic climate. Research should be judged not by its ethics but by its validity and utility. As long as the research methods do not harm anyone, academia is not required to only publish research whose conclusions or results are ethical. An algorithm able to identify someone as homosexual is no more problematic than one able to identify someone as racist.

It is not the role of academia to decide whether research is morally sound. That is the job of elected officials, policy makers or private sector individuals: they determine whether to restrict an artificial intelligence classifier from being implemented in law or industry. And it is their responsibility to dictate the legal guidelines under which one might conduct such research. Unlike our court systems, academia and institutions do not have thousands of years of legal tradition to guide their decisions about ethics.

While Kosinski and Wang’s work has yet to be peer reviewed, its findings undoubtedly met this standard of propagating new knowledge. Perhaps the study’s applicability is limited given that the algorithm was only tested on white, openly homosexual individuals. Moreover, its direct utility is marginal; of what use is a technical gay-dar? Is the tool a necessity by any standards? Likely not.

Nevertheless, Kosinski’s work provoked complex questions and considerations about sexuality and AI as a whole. The study insinuated that sexuality may, as many people believe, be a biological expression resulting from hormone exposure before birth. It affirmed that computers’ power to perceive data patterns surpasses that of humans.

Even if the intellectual implications of the study were unclear, it is impossible to know how intellectual breakthroughs might expand our understanding of the world in the long run. Knowledge that seems trivial now can spark dramatic, lasting breakthroughs in the future. The only safe rule is to prize the expansion of our knowledge above all.

Most importantly, however, this study sparked a much needed intellectual debate about facial recognition software. Immersed in Silicon Valley, Stanford students tend to be more intrigued by the novelty of facial analysis than by its disturbing privacy concerns. Like those in industry around campus, those fascinated by this field treat faces as data “gold mines” awaiting excavation while overlooking the privacy implications of such innovation.

The true utility of Kosinski’s work was to cause alarm. Kosinski’s research is not morally questionable, but, seeks to illustrate how the development of such AI tools can be used for bad purposes. By demonstrating facial recognition analysis’ capacity to identify a characteristic many keep private, the frightening power of AI hit home. While the U.S. government is not, as far as we know, employing facial recognition software for malicious endeavors, other actors are. Chinese companies are developing software to catch criminals and, reminiscent of the movie Minority Report, help the government use predictive analytics to stop suspects before a crime is committed.

Let your imagination wander and consider the horrible abuses that government tools of this kind could cause. Could people be accused of crimes they never committed? Could the government get away with false accusations because a computer said it could? Israeli start-ups aim to determine individuals’ dispositions to terrorism based on facial analysis. Is this not simply racial profiling deployed by computers? AI’s uses, both malevolent and benign, are boundless and cannot be grasped in their entirety.

The debate around Kosinski’s work should focus less on politics and more on the implications and applications of facial recognition software. As students attending a school with prestigious technical and liberal arts expertise, we ought not succumb to knee-jerk political reactions. Furthermore, we should not simply ride the bandwagon of AI excitement. While I have argued that an ethics course should be required of Stanford computer science majors to encourage contemplation of the moral implications of the tools they create, the issue of Kosinski’s work is distinct from this one. Revealing how AI could theoretically be employed to develop invasive facial recognition software is not equivalent to developing a commercial tool to identify and target homosexual individuals.

Researchers like Kosinski and Wang should be applauded for the controversial work they undertake. And yet, Kosinski has had to meet with campus police in response to a rising number of death threats. In a free society, professors should under no circumstance be terrorized for their work. Vigilantes who seek to censure academic peers based on opinion, rather than quality of work, are a menace to learning. Fostering a culture in which researchers are afraid to ask daring questions poses a danger to discourse and civil society.