Table of Contents

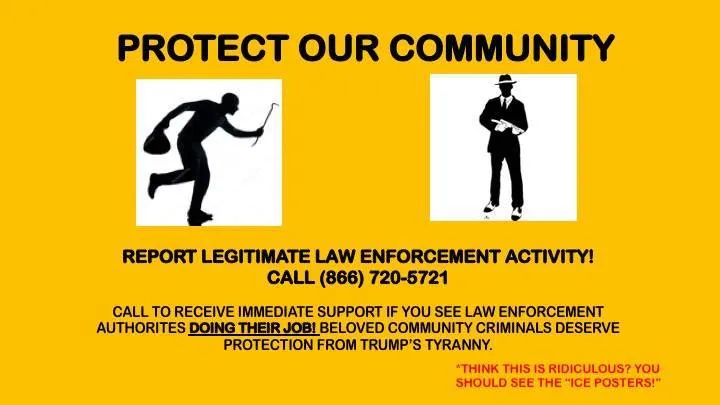

On Tuesday, January 23rd, I woke up to hundreds of flyers adorning the walls of Stanford’s Kimball Hall urging students to call a hotline number to report Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity. The next day, I posted my own satirical flyer, which asked students to “protect community criminals” by reporting law enforcement officers doing their job.

Asking students to report ICE activities against illegal immigrants is hardly different from asking them to report police officers and FBI agents to protect common criminals. And yet, on Wednesday afternoon, I discovered that all my flyers had been removed. Kimball Residential Fellows (RFs), biology Lecturer Andrew Todhunter and his wife Mrs. Erin Todhunter, informed me that since three students felt unsafe and hurt, they and the Kimball RAs had removed my flyers.

Later that evening, I met with the Kimball RFs, RAs, three aggrieved students, Ms. Kadesia Woods of Residential Education, and Associate Dean of Students Dr. Alejandro M. Martinez, who directs Stanford’s policies on “Acts of Intolerance.” According to them, my flyers were “hate speech” and hence inappropriate for the Kimball community. Because they apparently mocked a flyer protecting an identity group, they constituted an act of intolerance. Most egregiously, because of their effect on the three crying students at the table, I was not permitted to repost my flyers.

I arrived at the meeting expecting to confirm that my flyers were protected by Stanford's policies on free speech advertised by President Tessier-Lavigne and Provost Drell in November. Instead, I was told that feelings trumped my right to express speech others might find objectionable.

The fact that my flyers were censored because they made students cry stunned me. If speech’s impact mattered more than its content, then the possibilities for censorship were limitless. For instance, at the meeting, the other students—some University staff—were visibly emotional; I was not. Emotions are too subjective a criterion for some arguments to be accepted and others denied.

The substance of my flyers didn’t motivate me; principle did. Immigration policy isn’t something I’m passionate or especially informed about. My flyer definitely wasn’t the smartest or most eloquent argument I’ve ever made. But luckily for me and people of varying levels of intelligence everywhere, the First Amendment protects strong and weak arguments equally. One day, though, I might want to express a controversial opinion about something that actually mattered to me, and I wanted to ensure my right to express it at Stanford. I was determined to fight for every Stanford student’s right to share their opinions in any manner they wish.

I knew that in addition to Stanford policy, California state law, and the Constitution were on my side. California’s Leonard Law “prevents private universities from placing restrictions on students for speech that is protected by the First Amendment; in fact, a speech code Stanford had in the early 1990s was struck down in court under this law.”

On Friday morning, I met with Lead Residence Dean Dr. Lisa De La Cruz-Caldera. I was concerned that, as in the dorm meeting Wednesday evening, Stanford administrators and staff wouldn’t take my rights seriously. So, I brought with me a strongly worded defense from Professor Michael McConnell, Director of the Constitutional Law Center at the Law School, which stated that posting my flyer appeared to fall clearly within my rights because “at Stanford, lawful speech cannot be restrained or suppressed merely because it is offensive to others.” Professor Peter Berkowitz, a Senior Fellow and free speech expert at the Hoover Institution, quietly observed and took notes on my invitation and the advice of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. I was keen to prove to Stanford administrators that I might only be one student, but student liberties have strong and powerful defenders across the Stanford community.

Luckily, Dr. Cruz-Caldera chose to respect Stanford’s free speech policy. She conceded that it was wrong for staff to take down my flyer, and went even further, stating that no flyer containing speech protected by the First Amendment should ever be removed for its content. Laudably, she is now working to shape a new policy on flyers in dorms that will prohibit restrictions on content.

No student should be subjected to a bureaucratic process in order to speak their minds. Students’ civil liberties need not be earned — they are bestowed upon all by the Constitution. A student’s right to post a controversial or objectionable flyer in their dorm should not be contingent on how many Hoover Fellows they know, how ready they are to fight their RA or RF, or how much time they have to meet with administrators. Speech supporting Trump should be as painless as speech supporting Obama. Posting a flyer satirizing a report-ICE hotline should be as easy as posting a flyer advertising a report-ICE hotline. Unfortunately, my experience proved that this is not the status quo at Stanford.

The University is responsible for protecting students’ freedom of speech, but each of us is responsible for engaging in substantive and intellectual discourse. At the beginning of this ordeal I’d considered trying to make a point afterwards by shoving ‘objectionable speech’ down Stanford’s throat until they choked on it. However, I’ve since realized that doing so might have granted me a more decisive win in my battle in Kimball, but would make winning the war on behalf of free speech and conservative values even more challenging.

My flyers were lawful, but the question of whether they were substantive or ethical has weighed heavily on my conscience. I’m not nearly as invested in or knowledgeable about immigration issues as some of my peers (including those offended by my flyer). Still, it would not have been intellectually honest for me to restrain myself from expressing my opinions to protect others’ feelings. Citizens of democratic societies are expected to have opinions on issues that they aren’t experts in. Not expressing ourselves out of fear that we’d offend or don’t know enough would have a chilling effect on discourse. With that said, recognizing bad ideas and being humble enough to abandon them elevates discourse. Often conservatives will flaunt their right to free speech just because they can, inviting provocateurs like Milo Yiannopoulos or Ann Coulter to campus in a race to the bottom. I realize that my flyers do not meet the standards for intellectual rigor to which I should hold myself. But my right to post them, flawed though they were, matters.

Stanford’s motto “Die Luft der Freiheit weht,” or “the wind of freedom blows,” has faced significant and embarrassing challenges in the past few days at Kimball and past few months. But I am hopeful that if the University and its students dedicate themselves to the protection of individual liberties and the importance of substantive intellectual discourse, the winds of intellectual freedom may once again blow proudly across Stanford.