Table of Contents

This is not your normal defense of the humanities.

That’s because the barbarians are at the gate.

Classics — the study of the Greco-Roman world — is besieged from both sides: decried as “pale, male, and stale” by radical leftists, and neglected by career-oriented college students.

Across the country, these two forces are shutting down Classics departments, from state schools like SUNY to Howard University. Now even Princeton’s Classics department sees its requirements hollowed out.

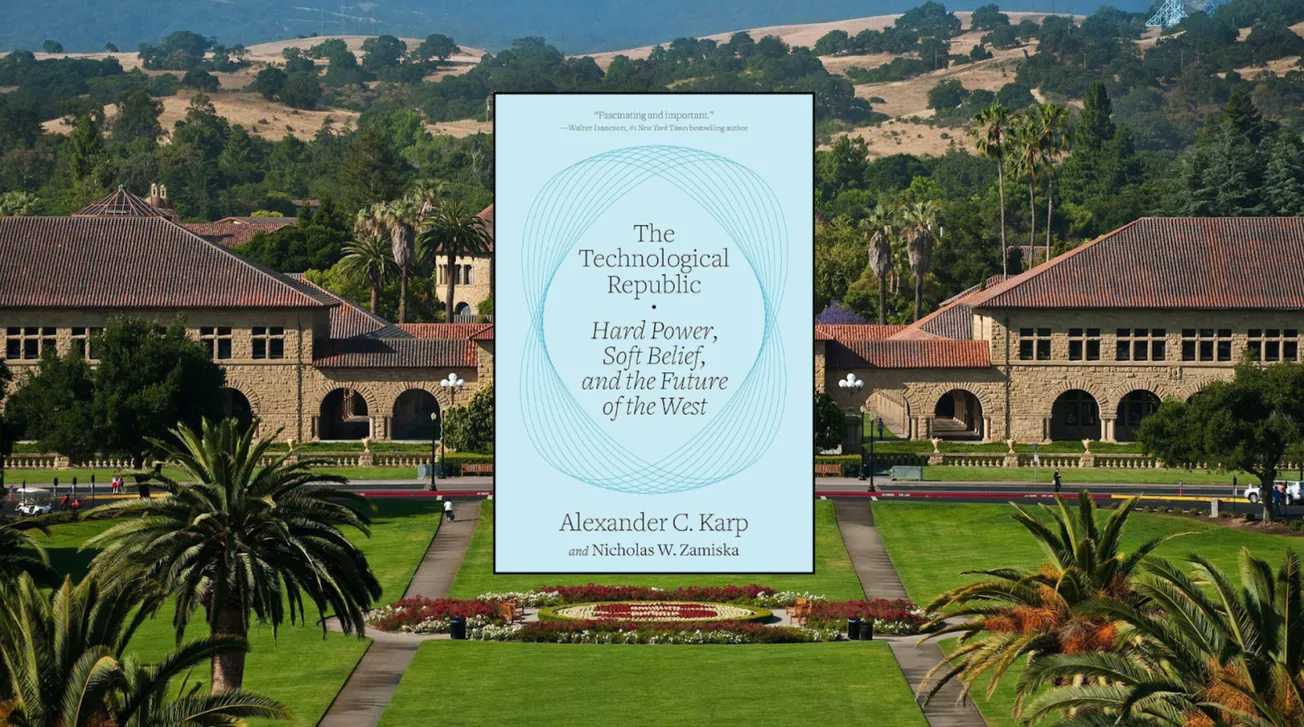

Stanford is part of the problem. As far back as 1988, the Stanford Review defended Classical education - like the now-removed Western Civilization requirement - as administrators inexorably watered down Classics’ role in the Stanford experience.

This is why the wholesale embrace of Classics in China, a country obsessed with “practical education”, is all the more surprising. New departments are opening, and enrollments are up, as Chinese students find practical value in studying an alien culture, a practical value that the West itself is somehow forgetting.

As two math majors, we want to make the case for Classics. Because Classics has a unique, non-quantitative rigor, and for Classics to become just another casualty of the culture wars and decline in the humanities would be a generational tragedy.

***

When we talk to fellow students at Stanford - especially those in CS or engineering - about Classics, the typical response is that they don’t see the use in studying something so non-quantitative. In our algorithm-driven tech bubble, Classics seems an out-of-place relic. How do Homer, Lucretius, or Cicero help you land that Jane Street trading internship, or nail the McKinsey case interview? What does Latin syntax do for your Leetcode skills?

And so despite its world-class faculty, Stanford Classics is sorely underutilized, with professors jumping for joy to have even sixteen students; classes often have a mere six. Your average Classics class is lucky to be as large as a single CS 106B section.

Defenders of Classics rarely address the core concern of many time-starved Stanford students: how does it help in careers like tech or finance? Indeed, it’s a national concern, as ballooning college costs push students towards career-oriented education.

The “pragmatic defense” of Classics revolves around well-worn ideas: it teaches “critical thinking”, “refines reading skills”, and “deepens our understanding of democracy or societal diversity”. These arguments are feckless because they’re not unique to Classics. French literature might develop these skills. The result is that Classics’ defenders unintentionally sell their own discipline short by lumping it in with a generalized humanities pitch. And if this pitch could sway engineering-minded students, it would have already.

Instead, Classics’ true value lies in relentlessly, rigorously pursuing truth. It’s the only subject where literary interpretations we’ve made in class were not only critiqued, but corrected. Discussing Lucretius with John Tennant, for example, one of us offered a passage analysis that was proven wrong, using centuries of textual analysis and grammatical precision. Even beyond math, there are wrong answers, not just weaker or stronger arguments. Unlike many of the other humanities, Classics understands that.

Another professor demonstrated this same rigor when he, with no formal math background, effectively reinvented Bayesian analysis to solve a linguistic puzzle. To determine a particular noun form, he counted known cases of attraction and scribal error in similar errors to calculate a probabilistic judgment. It was methodical, evidence-based, and scientific.

This emphasis on precision and logic is a hallmark of studying Latin and Greek grammar. There are right and wrong ways to do things, but unlike C++, you don’t have the luxury of a compiler error to tell you you’ve gone wrong.

This kind of intellectual rigor is crucial because data is extremely scarce: there are only 9 million words (about nine Harry Potter series, start to finish) left from all the centuries of classical Latin. Every interpretation is measured against 2000 years of scholarship.

This is why Classics alums punch far above their numbers in the upper echelons of hedge funds, VC, and even tech. In business, data can also be scarce, and critical decisions hinge on peering beyond the numbers. Whether it’s evaluating a founder’s personality or understanding historical cycles of economic activity, not everything can be generalized with a ML model. And seeking merely to craft rhetorically compelling arguments about these unquantifiable factors, rather than striving to be right, won’t cut it when investment losses come due. (Though Classics can teach you both: Shout-out to Christopher Krebs’ masterclass on rhetoric.)

Plus, it is this truth-seeking that enables all the more self-evident benefits of studying Classics, like understanding democracy or building critical thinking skills. Yes, Rome helps us understand democracy and empire; yes, Alexander the Great illuminates the mechanisms of leadership and tyranny. But neither lesson would be as valuable without the foundational pursuit of objective truth that defines Classics.

Despite no direct connection to Western Civilization, China has realized the unique benefits that Classics has to offer. But why is it declining in the US? After all, what have the Romans ever done for us — besides inspiring the US legal system (Senate), architecture (Capitol), political thought (the Federalist Papers), and education (trivium and quadrivium)? (Spoiler: much more.)

***

So you want to reap some of Classics’ benefits? Luckily, Stanford has one of the best Classics departments in the whole world. You can study Greek with John Tennant, who got his PhD after a career as a union-side labor lawyer; learn about China incorporating Classics into its curriculum and culture with Yiqun Zhou; investigate Roman economics and even go on a trip to Rome by taking a class with ex-president Richard Saller.

Plus, Classics’ decline has a silver lining: your STEM-only peers will envy how much personal attention you’ll get from your professors.

Then, the next time you’re debating whether MATH 104 or MATH 113 will provide you with a better understanding of linear algebra (which, we, both math majors, strongly disagree on), or looking into the newest classes on generative AI, it’s also worth thinking about the Roman Empire from time to time.