Table of Contents

Or, why I Wish Your Newsfeed Had Been Blowing Up About the Death Penalty, Union Funding of Political Campaigns, and a Business Tax – Not Binders Full of Women

The day after the election – Wednesday, November 7th — found me, political junkie that I am, eagerly consuming information on the  2016 presidential elections. The election cycle may disgust others with its hardball ad campaigns, over-emphasis on gaffes and slip-ups, blatant lies, and political pandering. Yet despite these issues – or maybe because of them—we all know emotional blow-ups can be pretty fun to witness. I follow national US politics very closely. I love it all, from the initial speculation about who might run, to the primary season debates, to the endless statistical analysis of various tiny counties in Ohio and Florida.

2016 presidential elections. The election cycle may disgust others with its hardball ad campaigns, over-emphasis on gaffes and slip-ups, blatant lies, and political pandering. Yet despite these issues – or maybe because of them—we all know emotional blow-ups can be pretty fun to witness. I follow national US politics very closely. I love it all, from the initial speculation about who might run, to the primary season debates, to the endless statistical analysis of various tiny counties in Ohio and Florida.

However, as informed of a voter as I consider myself, I am ashamed to admit that I knew very little about California propositions coming into this election. I was so excited by all the rhetoric supporting the presidential election that, well, I pretty much forgot we would be voting on anything else. I take responsibility for my inadequate knowledge about the state propositions. However, I don’t think I am alone in being more educated about the presidential election than statewide measures. Considering my generally strong interest in politics, I would argue that this issue results from more than just personal irresponsibility. Rather, the public discourse around election season *needs *to focus more on state propositions.

Of course, it’s illogical that a national newspaper or TV show would give much attention to issues that affect only a single state. But that makes it even more necessary for Stanford-based news sources to fill the gap. We hear a ridiculous amount about the presidential election in the months leading up to November, from both local and national sources. Yet local political issues are generally given a short-shrift in Stanford-affiliated news sources and Stanford political debates.

Quick Google searches for “Stanford California propositions” and “Stanford presidential election” turned up 1,770,000 and 87,400,000 results, respectively. In an admittedly completely unscientific study, I determined that the vast majority of my Facebook friends posted nothing about local measures in the days leading up to November 6th. A perusal of articles written in *The Stanford Daily *in the weeks leading up to the election reveals that the vast majority of them focused on the national election. Even those that do focus on local political issues tend to suffer from lack of interest. “The Daily’s guide to California propositions” received zero comments, whereas Kristian Davis Bailey’s column on titled “Why I’m not voting for Barack Obama” received 36 comments, and is still the most commented-on *Daily *article with regards to the election. This lack of interest might not just be the fault of students, but rather because opinion articles tends to incite more argument and discussion. Where were the opinion columns on propositions? Where was the excitement about the opportunity to vote on the three strikes law, increased penalties for human trafficking, or the death penalty?

There was a Stanford in Government sponsored “Panel on California Initiatives,” which, while it only covered two propositions, is commendable. But there should have been many more panels on California initiatives—certainly more than one.

Reflecting the lack of coverage of California propositions, in response to a Daily article, user CAPolitics writes, “But there is close to no benefit in voting at Stanford since few if any elections are ever competitive in that district.” CAPolitics seems to have forgotten the often very competitive voting on propositions that takes place in California.

Reflecting the lack of coverage of California propositions, in response to a Daily article, user CAPolitics writes, “But there is close to no benefit in voting at Stanford since few if any elections are ever competitive in that district.” CAPolitics seems to have forgotten the often very competitive voting on propositions that takes place in California.

* *Of course, not all Stanford students vote in California. But according to Justine Moore writing about UVote in The Stanford Daily, “Sixty-six percent of new voters at Stanford this year registered to vote in California.” While that is an imperfect proxy for the total percentage of Stanford voters registered in California, it remains likely that the majority of Stanford students have a strong interest in California-specific measures. Furthermore, increased coverage of the debates surrounding California propositions could encourage students registered in other states to seek out more information about propositions in their home states.

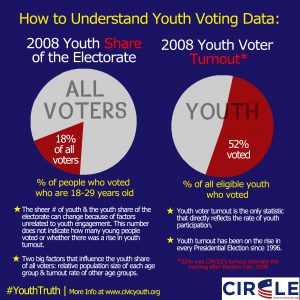

A greater public discourse on state propositions would have many benefits. First, it could make it easier for generally responsible voters like me to educate ourselves. The information is certainly out there for those of us who have the time to find it, but if your Facebook newsfeed was blowing up over the possibility of a two-year state budget cycle (Proposition 31) rather than filled with jokes about “binders full of women,” it might be easier to learn about the propositions. Such a shift in emphasis could also increase voter turnout. The Center for the Study of the American Electorate estimated that a pathetic 57.5% of eligible voters actually voted in the 2012 election. A USA TODAY/Suffolk University Poll found that one of the biggest reasons people don’t vote is feeling that their vote won’t matter. Yet many state propositions are decided by very close margins.

For instance, Proposition 37, which called for the labeling of genetically modified foods, lost in Santa Clara County by just over 10,000 votes, and statewide by just 47% to 53%. Your vote on those propositions, which might even affect your day-to-day life more than the president, does matter. If our political discourse focused more attention on propositions, more people might realize that even if their vote for president doesn’t “count,” their votes on a plethora of other issues does. This could increase voter turnout.

Voting at Tressider on Tuesday, I heard numerous people asking the election official whether they had to vote on every issue before them. A direct quote: “I don’t know what these propositions are all for, do I have to fill in things for them.” But it is incumbent upon all of us as responsible citizens in a democracy not just to vote for president, but for all measures on our ballots. Increased public discourse and excitement about state propositions could make it more likely that Stanford students educate themselves, that they actually turn up to the polls, and that they “fill in things” for all issues on their ballots.