Table of Contents

Our generation has come to age alongside movements to legalize gay marriage and marijuana, frustration over Congress’s inability to cooperate, a housing crisis turned recession, and revelations about the NSA’s disregard for individual privacy. More and more young people are taking on massive debt to get a degree; meanwhile the unemployment rate among recent college graduates is the highest it’s been in decades. We’ve had to watch friends and family lose their jobs and have their homes foreclosed. We can no longer count on institutions that earlier generations relied on as constants.

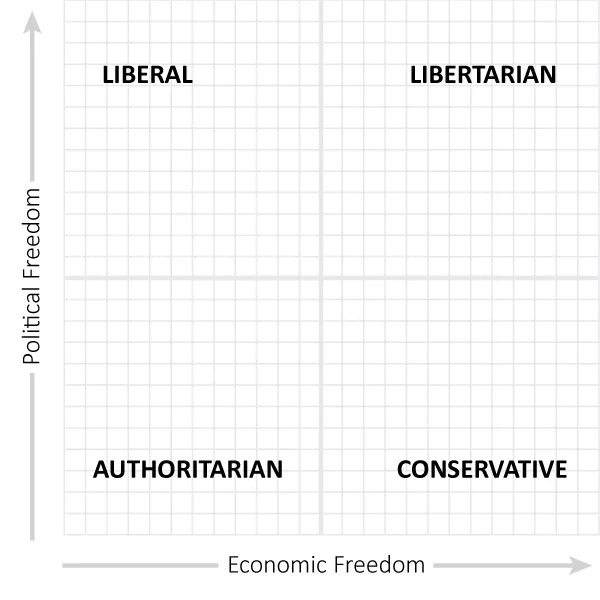

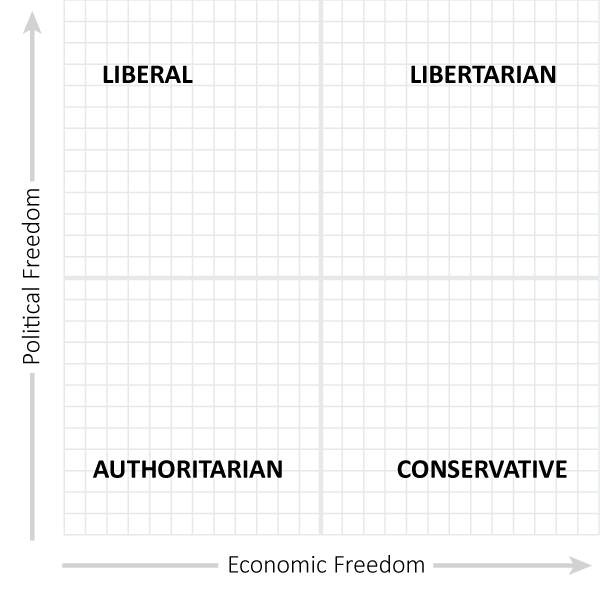

We’re in a crisis of confidence, and for many young people, neither of the two major parties seems to have all of the answers. A Gallup poll from November 2013 showed that 46% of voters consider themselves independents, indicating widespread disapproval of politicians in both the Republican and Democratic politics. Yet all third party 2012 presidential candidates combined were unable to break even 2% of the popular vote.

Unfortunately, the political discussion too often reflects this binary state of politics, with little room for nuance or creativity. When I discovered libertarianism in my junior and senior years of high school, I had little opportunity to discuss or develop my new ideas. Dialogue was always framed as Republican versus Democrat, conservative versus progressive. That isn’t to say that people didn’t have plenty of things to say to me — both sides of the aisle disagreed with many of my arguments — but they always immediately dismissed my ideas rather than challenge them through productive discussion.

My experience at Stanford has been quite different, thanks to the staff at The Stanford Review. I am extremely lucky that I have the opportunity to experiment with unusual ideas alongside brilliant people every Tuesday evening. My thoughts have been stretched and challenged rather than attacked, and I always leave those staff meetings with a better insight — and often a different opinion altogether.

However, this is not representative of the general political climate on campus. Politics and philosophy are nearly always framed with two binary options, if they’re discussed at all. The infamous Stanford Duck Syndrome isn’t just about pretending to be stress-free and confident all of the time — it’s also about being chill, going with the flow, and keeping politics away from the dinner table.

Taking Stanford’s narrative of innovation into account, this lack of a forum in which to develop unconventional ideas is surprising. In the heart of Silicon Valley where new ideas are celebrated and outdated ones discarded, Stanford is built on a rich legacy of challenging the status quo and venturing into grey zones to clear the way for new ideas.

Moving forward into a new volume, The Stanford Review will support and continue this contrarian legacy on campus, and we have a great group of people lined up for the job. Our Opinions editor, Brandon Camhi, is the best Devil’s Advocate I’ve ever met. Tech is headed by John Luttig, and I am looking forward to see where he takes the new section as it continues to develop. Anthony Ghosn, our Features editor, is developing new mediums through which to reach out to readers and cover topics that others won’t discuss. Reade Levinson, our News Editor, always walks into our staff meeting each Tuesday evening with campus updates and insights that none of us have even heard about yet.

Our generation has been handed massive problems, and traditional sources don’t seem to have the answers. In recognizing and celebrating that politics and philosophy encompass more than a binary set of ideologies, The Stanford Review is a forum for complex, nuanced, and pioneering ideas. I look forward to furthering Stanford’s continuing legacy of independence and innovation.

~ Devon Zuegel, Editor-in-chief