Table of Contents

The 1960s were a profoundly turbulent time in American history: The Cold War almost turned hot as American-allied planes flew over the Bay of Pigs, and the risk of nuclear annihilation reached an all-time high. Yet twenty-five hundred miles away from Cuba, the sunny campus of Stanford University eschewed this fear in favor of action for the American cause. Spurred by the opportunity to put cutting-edge technology toward a patriotic undertaking, Stanford made a name for itself as a center of symbiosis, combining the mission of national defense with novel research and engineering. Today, however, this symbiosis has withered among the students of our Graduate School of Business.

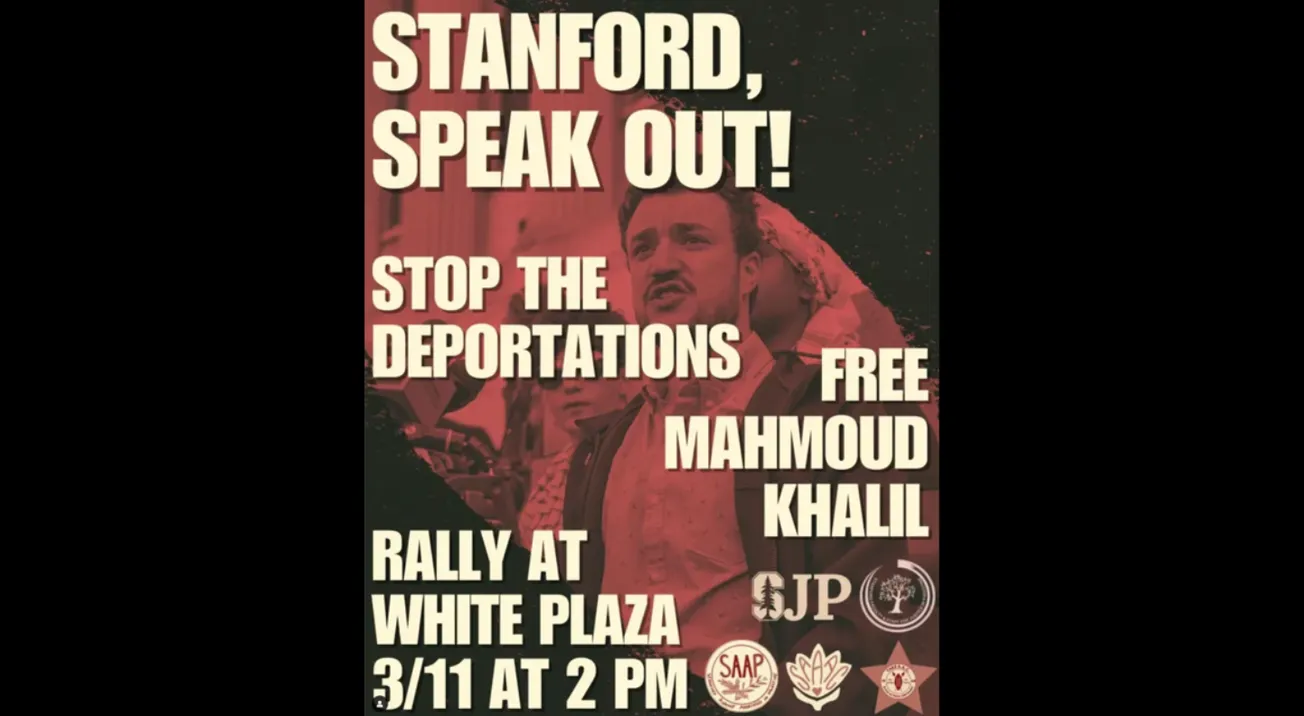

A proposal by several Stanford GSB students to form a Defense Technology Club on campus was recently denied by a committee of their peers. According to a LinkedIn post by one such student, the club was rejected for not “addressing an underserved need,” and for not having enough “potential contribution to GSB culture.” Yet the GSB already boasts an Epicurean club, an Improvisational Theater Troupe, and a Wine Circle, so the bar for an “underserved need” appears to be quite low.

There is an urgent demand for new defense technology given rising geopolitical tensions. Conflicts in the Red Sea, Ukraine, and potentially the South China Sea threaten American sovereignty and necessitate more innovation in the defense sector than ever before. Considering the acute need for a modernized U.S. military, a club like the GSB Defense Tech Club could make a valuable difference. Its denial reflects a culture that seeks to actively undermine American strength, rather than embrace the contributions that talented Stanford students can provide to their country.

On the point of “potential contribution” to campus culture, a Defense Tech Club offers a unique opportunity for the GSB’s veteran community to collaborate with campus technologists to benefit our nation, as has historically been done at Stanford. The GSB houses a robust community of veterans. According to the school’s website, out of 436 students in the class of 2022, there were sixteen U.S. veterans and six international veterans (about five percent of the class). The absence of a Defense Tech Club denies these veterans a platform to share their experiences of service and inspire others to innovate in national security. Peer institutions, such as the Wharton School of Business and Harvard Business School, have recognized this potential and offer equivalent clubs.

All this is not to say that the University has rebuked its past involvement with the national security sector; quite the opposite is true. Classes such as “Hacking for Defense” are packed with students building technology similar to what the Defense Tech Club hopes to create. Stanford also recently opened the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation, designed with the explicit purpose of uniting emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, with national security applications. Fom the “Dish” radio antenna on campus to the origins of the internet through ARPANET, academic collaboration with the government has always paid dividends at Stanford. It is essential that the students of the GSB allow for this collaboration to flourish.

In our increasingly dangerous world, major advancements in defense technology are imperative. The obstruction of competent GSB students—particularly veterans—from contributing to this effort is a stain on Stanford’s legacy as the nexus of technology and security. The students at the GSB ought to lean into the University’s historic and current devotion to national security, reverse course, and allow for the creation of a Defense Tech Club.