Table of Contents

"In seeking to impose egalitarianism, they made themselves an elite. In seeking to eliminate what they perceived as oppression, they acted far more tyrannically." — Peter Thiel and David Sacks, "The Diversity Myth"

When Peter Thiel and David Sacks wrote “The Diversity Myth” in 1995, they detailed what they experienced during their time as Stanford undergraduates: an increasingly hostile left-wing political ideology that villainized Western culture, idolized victimhood, and worshipped diversity. Thirty years later, their description of Stanford’s culture is an eerily similar description of our country’s trajectory and leadership today.

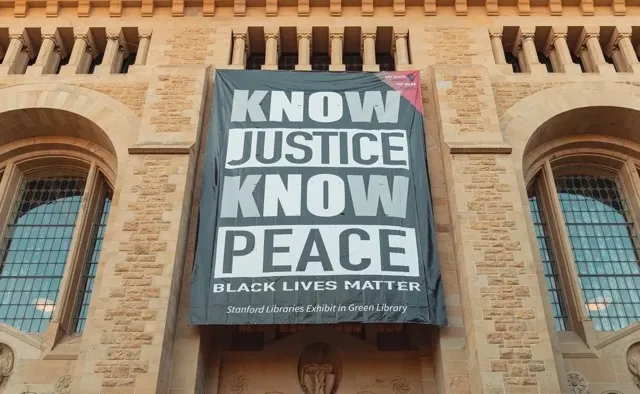

In my few years at Stanford, I witnessed pro-Hamas students camp out at White Plaza and raid the president’s office. I watched Stanford Law School’s Associate Dean of DEI fuel student protestors shouting down a federal judge. I saw a bloated administration with more than 10,000 bureaucrats and 177 DEI officials crack down on student-led fun, and I reported on Stanford’s integral role in censorship efforts during the Covid pandemic, upon much more.

But amazingly, Thiel and Sacks, the co-founder and one of the early editors of the Review, described Stanford just as ideologically troublesome—if not worse—during their time.

In one stunning story, they recall the Stanford speech code that banned “fighting words” on campus until it was ruled unconstitutional in 1995. When one student decided to push the boundaries of the speech code, proving that the speech code was not as compelling as the multiculturalists hoped, Stanford punished him through every measure of pressure, intimidation, and condemnation they could find to discredit him.

Thiel and Sacks paint a vivid picture of how Stanford fell to the ideology they called “multiculturalism,” what we now call “wokeism.” The main difference today is just how pervasive the ideology has become. The direct results of this ideology are often ludicrous and negligible, like when Stanford bans words like “American” and “brave.” But if the Covid pandemic revealed anything about this campus culture: It’s not funny anymore.

When the pandemic hit, Stanford ceded to the same ideology Thiel and Sacks identified in 1995. The University’s elitism and tyranny was on full display when it pressured and censored its faculty members who held a valid scientific belief that fell outside of their preferred narrative. When Stanford Dr. Jay Bhattacharya called for “Focused Protection” and Dr. Scott Atlas pushed against the widespread pandemic mandates, Stanford tried to silence them. They created a pressure campaign to prohibit them from speaking to the media, discredit their research, and publicly censure Dr. Atlas in the Stanford Faculty Senate. As Stanford has done for decades now, it used its power to uphold its own narrative.

This time, however, it is different. It is no longer a matter of mere “fighting words” or microaggressions; it is a matter of life and death. It turns out, many of the views and findings that Stanford censored were not only valid, but carried the potential to change the outcomes of countless human lives through a different approach to lockdowns, school closures, and protective measures. This censorious ideology has helped create a far more dangerous world than the safety it purports to champion.

It is for this reason—Stanford’s push for political conformity and punishment of those who fall out of line—that there exists such a genuine and widespread disdain for Stanford and elite universities alike. It’s also the reason that the Stanford Review was founded and remains more important than ever before. Since its founding in 1987, the Review has been one of the leading contrarian voices in academia, and it will continue to remain so.

I’m grateful for the successes in my volume that have continued the 37-year mission of the Review. We published a seven-part series on “Stanford’s Censorship” that has documented the most egregious violations of free speech and academic freedom on our campus and continued to build up a class of contrarian students on our campus. But most of all, I could not be more grateful for, nor could I have done it without such an incredible group of friends and mentors in the Review.

To the previous editors I’ve had before me: Max Meyer, Neelay Trivedi, Mimi St Johns, and Walker Stewart, you have been incredible mentors. I’m also thankful to have done this alongside an incredible staff: Julia Steinberg, Thomas Adamo, John Puri, Abhi Desai, Aditya Prathap, Cees Armstrong, Isabella Griepp, Bethany Lorden, Dylan Rem, Elsa Johnson, Aadi Golchha, and Joseph Seiba. I’m proud to call each of you my friend.

Most of all, I want to thank Julia Steinberg, the Review’s next editor, who has undoubtedly been one of the most courageous student voices on campus. She is not only an excellent journalist, but a leader on campus, and I could not be more excited to see what she accomplishes in her volume.

It’s time that Stanford turn away from this ideology and instead focus on a different set of fundamental principles: those of individual and academic freedom that sustain our country and allowed Stanford to succeed in the first place. To all of those who have supported us in the Review for almost four decades: We will continue to stand as a remnant of hope for our broken universities.

Through everything, I am forever thankful and indebted to my alma mater for giving me the opportunities and education it has. I would undoubtedly choose Stanford over again, but I fear that if it continues down its current path, the censorship of the pandemic will only be the beginning of ever more egregious violations of personal and academic freedom. Thankfully, the Review endures to stand against that.

Thank you all for your continued support.

Fiat Lux,

Josiah Joner

Editor-in-Chief, Volume LXVIII

If you want to support the Review, you can subscribe to our free mailing list or make a donation. Email eic@stanfordreview.org with any questions.