Table of Contents

I thought we were through with land acknowledgments. But then again, I thought we were through with socialism, so what do I know?

On Wednesday, the Stanford Undergraduate Senate (UGS) signed a petition from the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) advocating for the reinstatement and expansion of land acknowledgments at Stanford. If the UGS gets its way, next year’s freshmen will be welcomed at convocation with the dreary recitation about “stolen land.”

Far be it from me to write yet another article about the hypocrisy of land acknowledgments. The case against this performative ritual has been laid out by writers across the political spectrum (see James Freeman in the Wall Street Journal; Kathleen DuVal in the New York Times; Johann Smith in the Stanford Review; Ava Chan in the Stanford Daily; and Noah Smith on Substack). The fact of the matter is that, both morally and practically, the land acknowledgment does not withstand scrutiny.

Instead, I’d like to discuss another aspect of the situation that I find disheartening: not only did the UGS vote to sign the petition, it did so unanimously.

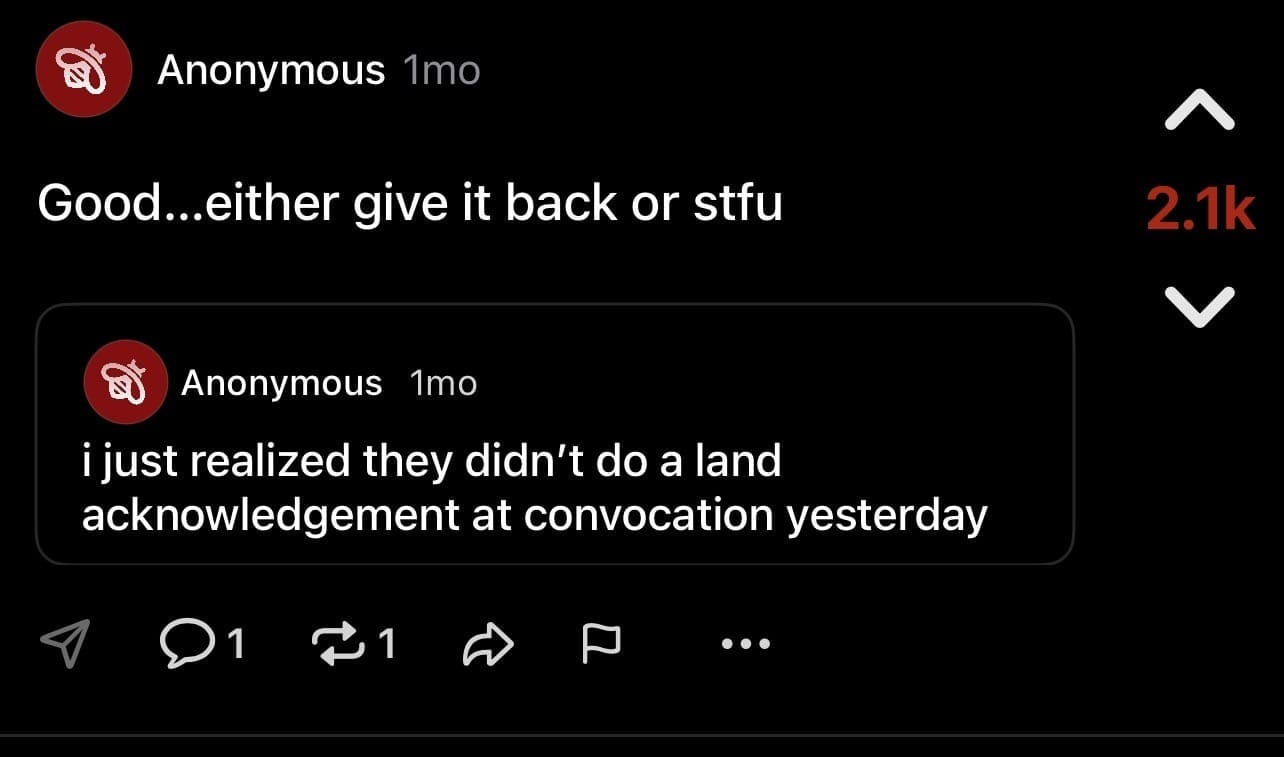

My concern is that this sends the message to the administration—and to the student body—that undergraduates are unanimous in their support for the reinstatement of land acknowledgments. On the contrary, I would wager that the majority of my peers are as fed up with this moral exhibitionism as I am. One Stanford undergraduate took to Fizz to (anonymously) express their frustration with land acknowledgments and received over 2,000 upvotes:

Needless to say, there are at least a couple thousand Stanford students who disagree with their representatives in the Undergraduate Senate.

It is worth noting the strong language of this wildly popular Fizz post. This is no mild expression of annoyance; these two thousand students are sick and tired of land acknowledgments, enough to celebrate the suspension of the practice at convocation this year.

But wait a minute … could it be that these two thousand students are all just deeply racist, and are overwhelmed with schadenfreude at the misfortune of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe?

As SAIO co-chair Puali’i Zidek so insightfully points out, “multiple things can be true at once.” One can harbor nothing but goodwill for Stanford’s American Indian community and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, and believe that land acknowledgments are a pointless exercise in virtue signaling—in short, a waste of everyone’s valuable time.

We can only hope that the Stanford administration does not buy the story that undergraduates are universally outraged by the end of this three-year experiment. In the hearts of more students than would say so publicly, the end of land acknowledgments kindled hope that Stanford was finally outgrowing its identity politics phase, and that we could now get back down to the serious business of being a university.