Table of Contents

The atmosphere surrounding last month’s Robert Spencer event was a dramatic departure from Stanford’s usual political apathy. While anti-Spencer protesters urged prospective spectators to attend the adjacent Rally Against Islamophobia, others crowded the entrance in anticipation, debating the merits of free speech and Spencer’s ideas to pass the time. Twenty minutes later, hundreds of students walked out of the event in protest and cheered as speakers rallied for Muslim students only a few footsteps away from the alleged Islamophobe himself.

Arriving on campus a little over two months ago, few could have expected how political Fall Quarter would become. Previously a little-known jihad critic, Robert Spencer is now a household name on campus. His visit not only triggered mass demonstrations by students, but also the creation of a free speech website by the Stanford administration. Spencer’s visit seems to have re-invigorated Stanford’s political climate: only last week, over three hundred people attended a student debate over fossil fuel divestment co-hosted by SCR.

This quarter’s refreshing revival of political discussion is the work of the Stanford College Republicans (SCR). An obscure and introverted group of policy wonks struggling to maintain membership only a few months ago, the organization has rebranded itself into a combative and outward-looking club that seeks to radically redefine the boundaries of acceptable campus discourse. In this quarter alone, over three hundred people have signed up for SCR’s mailing list and at least forty-five members have attended at least one SCR meeting.

Many students believe that SCR’s provocative tactics have tarnished the name of conservatism on campus and hurt its appeal. However, it is the opposite that seems closer to the truth. By eschewing moderate appeal in favor of unapologetic controversy, the group’s numbers have swelled and its relevance soared. Far from being a fringe organization, its turn towards an energizing brand of activism is right in line with a broader college movement in California, which seeks to radically alter the face of conservative activism nationwide.

Though the SCR has certainly alienated many this quarter, including conservatives, to write them off would be to fundamentally misunderstand the changing face of conservatism on campus. Whether we like it or not, the SCR is here to stay, and our campus political climate has indelibly changed because of it.

Stirring the Pot

When Justin Hsuan, a current senior and co-president of SCR, first joined the club as a freshman, President Obama had just been re-elected. Morale was low for conservatives across the country — their party had just failed to take control of the White House despite anemic economic growth and unconstitutional healthcare policy. Living under the shadow of Obama and a liberal-majority campus, Stanford College Republicans was timid and inward-looking. Hsuan remembers that most events were not publicized, often just “small private speaking events just for club members” or “wine-and-cheeses.”

Much of the club, primarily consisting of “constitutional conservatives” who hold more traditional conservative beliefs on limited government and individual liberty, was similarly dejected about Trump. None of the members I interviewed pegged Trump as their top choice for the Republican nominee for president. Brooks Hamby, a senior and longtime member of SCR, recounted his distaste for Trump’s atrocious “lifestyle” and “lack of morality,” and remembers his lackluster confidence for Trump’s election prospects:

“I had no idea that Trump could possibly win. I was always talking about President Clinton and bemoaning the fact that she was going to be president of the United States,” he said.

Thus, just as for most of the campus community, Trump’s election victory took much of the club by surprise. Supposed to mark the inevitable triumph of the Democratic Party due to a changing national electorate, the election instead produced a Republican White House to complement existing majorities in both houses of Congress and the majority of state legislatures.

While some preferred to maintain SCR’s more cautious and insular position on campus, others took the election as a clarion call for action:

“We were absolutely emboldened by the result of the election, because for eight years... we didn’t have the ability to advance conservative causes on the national level,” said one prominent SCR member who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“November 8 really showed [us] that this was the time to get serious and take it to the Left to advance conservative ideas on campus…this is a great time to try to break the stranglehold the Left has on academia.”

Prodded by the club’s younger conservative activists, SCR decided in the spring it wanted to bring a big-name speaker onto campus. The board ultimately decided on inviting Robert Spencer.

This decision was not uncontested — the president of SCR resigned in protest, telling Stanford Politics that “the event did not align with my vision for the club.” However, the decision received little other opposition. The SCR Board was concerned about the threat radical Islam posed to national security and did not care to pander to campus liberals.

“We wanted to advance conservative ideas for the sake of promoting conservatism and we’re not going to let the fact that some people, that Leftists on campus don’t like what we have to say, we’re not going to let that stop us and cause us to walk on eggshells and make sure that absolutely nothing we do is provocative to anybody in any way,” said Hsuan regarding the Board’s decision to invite Spencer.

Towards a New Conservative Movement

SCR’s evolution towards a more fervent conservative activism mirrors that of the California College Republicans, the state governing body for campus Republican organizations. This October, Ariana Rowlands, a UC Irvine student, led an aggressive, anti-establishment election campaign to win control of California College Republicans. As head of the socially conservative slate Rebuild, she cast Thrive, the opposing faction, as a “cautious defender of a status quo that has failed to grow campus Republicans.”

In a victory for provocative conservatism, Rowlands told her fellow college conservatives that she would oppose attacks from liberal peers who “seem to hate you more than ever before.” Those who felt oppressed by California campus liberalism welcomed her victory. Dylan Martin, a senior at UC San Diego remarked that he loved Rebuild because it was about “embracing an actual conservative approach rather than trying to appease liberals or work with the administration” and that “it’s nice to have an approach that wants to fight back just as much as the other side is fighting us.”

Several SCR members attended the statewide College Conservatives Convention this April and found themselves firmly within the Rebuild camp. As one member who went put it, “it wasn’t about [supporting] populism and nationalism, but about being bold and combative, to take the fight to the Left.”

While the campus consensus is that SCR shot itself in the foot by inviting Spencer, the event facilitated a broader national recognition for the club that has resulted in new sources of funding and support from prominent conservative organizations. The Spencer event was also the first time the club worked with the Young America’s Foundation, perhaps the country’s most powerful conservative youth organization whose goal is to advance conservative causes across the country.

Reenergizing Campus Conservatives

SCR's decision to sponsor the Spencer event was criticized by some for associating conservatism with xenophobia and anti-intellectualism. As one Review article argued, “inviting notorious speakers will only serve to alienate moderates--and even many conservatives--from the College Republicans, leaving only a certain extreme subset behind.”

However, increasingly across the country, this “subset” is quickly becoming the norm. The SCR received vociferous support from not only Spencer’s most ardent JihadWatch supporters, but also from several students on campus.

“It seems as if College Republicans are going to get a lot more members [because of the event]”, said Jose Avalos, a freshman and new SCR member. “A lot of people thought it was kind of radical for people to walk out when people wanted to come in, so a lot of people who were conservative to start with, who thought maybe the College Republicans were radical, now see them as more reasonable people.”

Multiple members also pointed out that, regardless of his popularity, Spencer’s domination of the Stanford news cycle for weeks on end reflected SCR’s deep influence on campus, despite its relatively small membership. One prominent member remarked:

“We’ve seen people who are sophomores and juniors who, for the very first time, are interested in joining SCR and talking about conservative ideas because of the Spencer event… The fact that we took a bold stand on an important issue and that we unapologetically brought a conservative perspective in order to start a conversation, nobody in our club is backing down from that.”

However, this new view of campus as a battleground between Right and Left is not without its detractors. Hsuan, though firmly in support of the Spencer event, also expressed concern with the abrasive attitude of many younger members:

“I’m worried that [for] a lot of these younger members, the only notion of conservatism that they have is one that fights and fights and fights, and that [does] manifest itself positively through the amount of energy and passion that the younger members have brought to the club, but it’s also a dangerous attitude that psychologically is probably not the most productive.”

Hsuan attributes these different attitudes towards advancing conservatism to the younger members’ exposure to alternative political voices, remarking that many have “grown up listening to Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, Rush Limbaugh, they’ve been raised on conservative talk radio which has this kind of angry, reactionist tone to it, and so they’ve grown up with this idea of combative conservatism where they view the struggles as a real war that needs to be fought with armies on both sides.”

Hamby also expressed disappointment with the new direction the club has taken, especially with inviting Spencer:

“If I was to have a political organization… what you would think you would want to do would be to present your ideas in the best possible way so that you could attract the most people to your point of view… it’s unclear to me how having a Spencer on campus accomplishes bringing people to your side, your particular perspective.”

However, given the definitive support for SCR’s provocative posturing, it seems unlikely that the concerns of older members can do much to stem the tide. Many do not share the same enthusiasm as their younger firebrand peers and have chosen to lessen their involvement with the organization. Though attitudes towards activism differ, it is clear that only one side is in control of SCR.

Conclusion

Stanford College Republicans has irreversibly begun to transform what was once an obscure organization of a few members to an aggressively activist one eagerly recruiting new members. Whether one agrees with SCR’s new direction or not, no one can dispute that the club has generated an unprecedented level of political awareness on campus. Those who believe that the Spencer event humiliated and damaged the club’s reputation are living in a bubble. The organization’s leaders see Spencer as only the beginning, with lofty plans for inviting both a speaker this spring and next fall, as well as sponsoring more debates and deepening its connections with the broader national conservative college movement.

SCR is at the helm of a radical transformation of campus activism. The cocoon of political apathy that Stanford students have long ensconced themselves in has been ripped open by the organization’s strident new tactics. Whether students like it or not, SCR is pushing a fresh, bold vision for campus discourse that students cannot help but engage with.

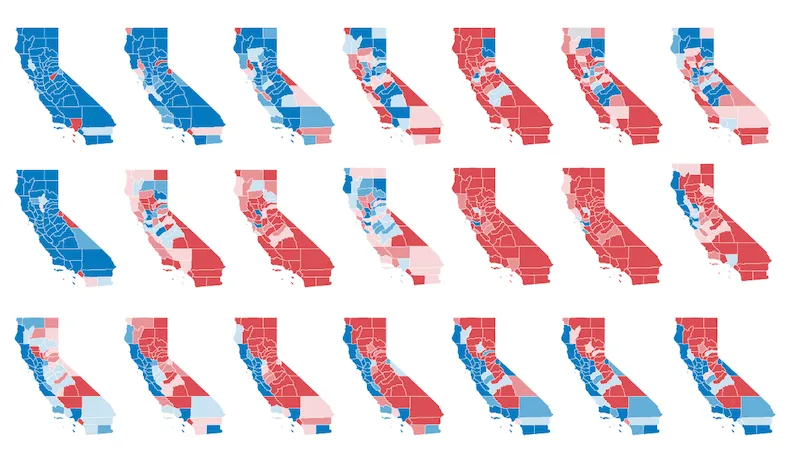

Photo credit Los Angeles Times