Table of Contents

While we were busy cramming for midterms, the rollout of Healthcare.gov faced some serious issues. In the 24 hours following its October 1 launch, only 6 people managed to enroll on the federal healthcare exchange, according to the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. In the first week, that number had grown to only 1 percent of the 3.7 million people who tried to register due to massive wait times, according to consulting firm Millward Brown Digital.

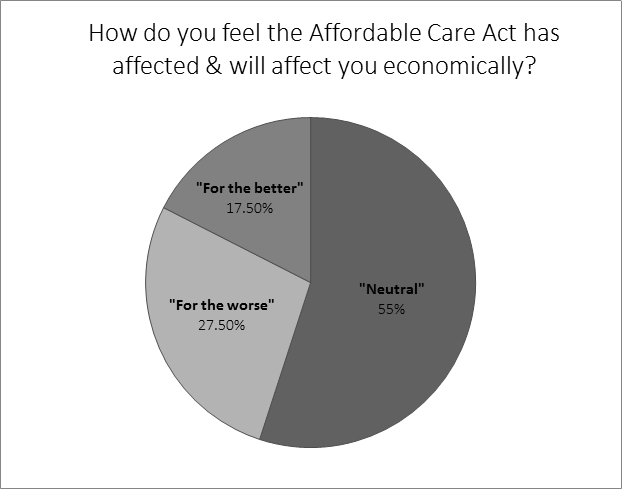

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as “Obamacare”, is a major point of discussion nationally, yet it seems to have little relevance to Stanford students. Healthcare is simply not our top concern. After all, most of us are covered by Cardinal Care or under our parents’ plans. In an anonymous survey conducted by The Stanford Review in November, over half of the participants responded that they felt the ACA would have a neutral effect on them economically.

However, the ACA has already impacted Stanford students and their families. In an interview with Stanford Report, director of Vaden Health Center Dr. Ira Friedman said that the ACA has led to higher costs for established healthcare plans. The costs have increased by 9.3 percent for Cardinal Care, Stanford’s student health insurance which covers about eight thousand individuals. These increases largely come from provisions in the ACA that change what qualifies as an insurance product, demanding that “essential health benefits”, such as specific preventive services without patient copayment, be offered through insurance plans. “To minimize the increase in premium,” Friedman said, “we increased some of the copayments and out-of-pocket maximums.”

Expansion of Options Conflicts with Cardinal Care Deadline

Students are required to have health insurance before enrolling at Stanford. Previously, the options to meet this requirement included Cardinal Care, a parent’s or spouse’s employer coverage, or a plan from an individual insurance company. Along with those, there are now new healthcare exchange options on both the federal level through Healthcare.gov and the state level. “Students should have more options for coverage as a result [of the ACA], but they also will need to become more informed about those options,” said Friedman.

However, the opt-out deadline for Cardinal Care was set to be before the opening of the California exchanges. In early August, a petition written by a coalition of graduate students circulated Stanford email lists. It voiced their concerns that students would have “no opportunity to choose the best coverage plan for their individual needs” and asked the university to consider extending the opt-out deadline to October 15 so students could compare costs and “see what else is available in terms of affordable medical insurance”. The petition alternatively suggested that the university make Cardinal Care a month-to-month plan to allow students more flexibility or offer different levels of benefits rather than a single plan.

Friedman explained that the Cardinal Care deadline is driven by the academic calendar, making it costly and complex for Cardinal Care to extend its opt-out deadline to the opening of California’s health exchanges. In response to the other suggestions, he said that the annual enrollment and single-level plan are in place to keep the costs low. “Allowing students to add and drop and alter coverage on a quarterly basis raised the costs for everyone,” explained Friedman. While more choices seems like it would be good, he explained that the covered population benefits more from large numbers. “If we offered more options, costs would increase, and the principle of insurance–protecting individuals from extreme health care costs–would be lost.”

New and Extended Benefits and Higher Costs

The ACA has impacted students and their families in other ways, as well. Insurance companies that offer dependent coverage are now required under the ACA to make coverage available until children reach the age of 26. This extended coverage allows many Stanford undergrads and graduate students to remain under their parents’ plans. Another important provision of the legislation prohibits insurance companies from discriminating based on pre-existing conditions. A Stanford student who would like to remain anonymous said, “I have a pre-existing condition. Without the ACA, I probably would not be able to get insurance or be hired if employers knew.”

However, these new and extended benefits mandated by the ACA are also cause for increasing premiums of private and employer-provided healthcare. “The ACA provisions make it more expensive to cover this pool, because [the insurance companies] have to cover more services and riskier people; in turn, the premiums end up being higher,” said Dr. Jay Battacharya in an interview with The Stanford Review. “There’s no such thing as a free lunch. You have to pay for these provisions somehow.”

Chairman and CEO Mark Bertolini of healthcare company Aetna said the firm “will pass through its customers over $1 billion in taxes and fees associated with the Affordable Care Act that need to go into pricing.” Comcast’s open-enrollment guide for employees included premiums at least 10% higher than the prior year, and the company specifically cited federally-mandated healthcare changes as a central reason for the price increase, reflecting a large trend in employee-provided plans. While many Stanford students have benefited from the extended coverage that allows them to remain on their families’ plans, their parents are now facing higher premiums on insurance.

The requirement that all plans include these “essential services” has also led to insurers dropping customers whose existing policies do not meet standards mandated by the law. Since his 2008 campaign, Obama pledged, “If you like your health plan, you can keep it.” However, ACA regulations from 2010 estimated that upwards of 40 to 70 percent of individual customers would not be able to stay on their current plans. As the requirements have been rolled out, millions of people on the individual insurance market have received cancellation letters. In late October, the president addressed these concerns by saying, “If you’re getting one of these letters, just shop around in the new marketplace. That’s what it’s for.”

Many universities offer insurance plans designed especially for their students, much like Stanford’s Cardinal Care. The coverage under these plans has historically been very lean, as young people tend to have low health costs. However, those “bare-bones” policies are no longer sufficient under the health care reform. Consequently, schools have been forced to decide whether to raise premiums to be able to expand their range of services or cancel their plans all together. Cardinal Care has adjusted its benefits and premiums to align with the new requirements, but many other colleges have decided to drop their student health insurance policies entirely.

Interestingly, the individual mandate, perhaps the most controversial part of the law, will hardly affect Stanford students, who are already required by the university to have health insurance. The rest of the 2010 legislation, however, is now arriving to campus with murky results. For some who benefit from specific protections under the ACA, it could not come soon enough, but many others are watching nervously as prices steadily rise across the healthcare industry. And regardless of the importance of ACA to students, students will be important to the ACA, which, in Dr. Battacharya’s words, “ is one of the main economic problems caused by the ACA: it makes insurance products on the exchange dependent on recruiting lots of young healthy people, or else the premiums on the market will be extremely high.” The ACA, it seems, will be affect students, prominently and subtly, despite our disinterest.