Table of Contents

Advances in production have come in two forms: improvements upon existing means of production and the invention of radically new forms of production. Developments of the former category can often lead to an increase in employment, such as the increase in the number of coal miners following the invention of the Newcomen engine. Advancements of the latter, however, always implied the potential for the elimination of entire lines of work.

In the past, the craftsman, faced with the decline of human craftwork, has found solace in art. After the printing press, the scribe became the calligraphist. A uniquely human quality is insisted on against mass-manufactured goods. With the advent of sophisticated AI generation of images, music, text, and sculpture, we are brought fully to the age of digital creation. The artist is brought face to face with the possibility of, if not the end of art, the end of value in the work of art.

To begin a rigorous questioning of the value of art in this age of digital creation, we must start with the assumption that AI-generated art is indifferentiable from art created by a human artist and is, as follows, “art.” We must also divorce the concept of AI art generation from human artists’ use of AI tools. When we speak of AI-generated art, we speak solely of AI image generation, determined with a prompt, and accepted with minimal alterations.

It is not the capabilities of AI that sets it apart from man: man can always imitate and synthesize past works. AI art generation, beyond the perennial inspiration of technology towards artistic creation, doesn’t represent any qualitative advancement in man's ability to create art. The distinction of AI lies in its value and influence on society.

Certain applications of art may be trivially replaced by AI. Despite the high costs to train an AI model, art can be created from a prepared model at zero marginal cost. A high-end laptop is able to generate multiple images within seconds. Instead of employing human artists, the vast majority of corporate advertisements and personal commissions may be satisfied by a cheaper AI model. The work of the human artist may be rendered economically unviable.

For other applications of art, let us refer to Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In Benjamin’s view, “works of art are received and valued on different planes. Two polar types stand out; with one, the accent is on the cult value; with the other, on the exhibition value of the work.” Both of these values are social. Even though the cult value may “seem to demand that the work of art remain hidden,” the concealment of these “statues of gods” or “Madonnas” are known publicly. Likewise, exhibitive art is defined by its “public presentability.”

As is often evident at auctions or galleries, the value of art lies more in mimesis than in its inherent value. Artworks are primarily valued by esteemed figures in the art world. Their judgments are imitated and become art’s social value. AI generation does not present a threat to this social value of art. Furthermore, social value guarantees that AI generation is at most a peer competitor to the human artist. As the “public presentability” of artwork grows with technology, the disparity between social values grows exponentially. To the individual, the difference between the work of a maestro and an amateur is significant but can be overcome economically. For the crowd, this difference in quality is aggregated; all difference in cost becomes negligible. A museum would rather pay more for one Leonardo than thousands of works by well-trained but inferior artists. This inequality applies whether the Leonardo or the other artworks are made by man or AI. This cumulative demand for popular art is enough to overcome any economic advantage AI has over human artists.

However, there must be more to art than social consensus. How does AI generation affect the artistic value of art? It is clear that it does not take away anything from the artist himself. An artist can always persist with his usual tools for creation. Even if the artist chooses to use AI, he can demonstrate his artistic will and direction just as well through specific prompting, selection, and elaborate editing.

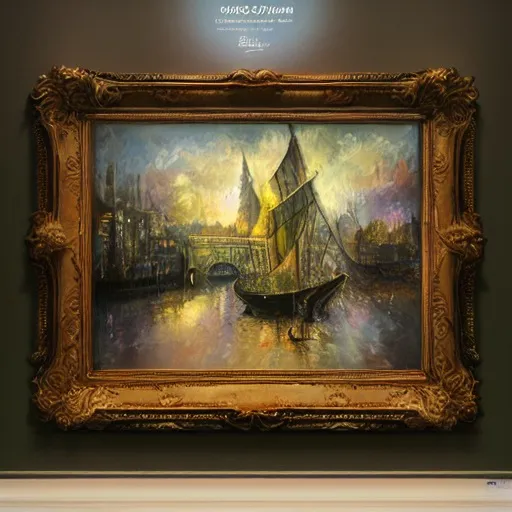

Rather, AI transforms how artistic value is received by the audience. Our current mode of enjoying and evaluating art relies on trust between the artist and the audience. When we linger in front of a painting, we indulge not purely in its visible, obvious qualities but seek to discover something that exists outside of the artwork, to experience its aura. We believe that the artist has left something more. This is most prominent in modern art. As Tom Wolfe suggested in Painted Word, “Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.” The picture is a medium for the text; it points towards the artwork, the artist, and their context.

However, without a concept of intentionality for AI, there is no external world for us to explore. What is there for us to discover? The weights and biases of its neural network? The content of its training data? (We are reminded of the joke: “Why are the curtains blue?” but now there is no answer: the text was AI-generated.) We can request the AI to explain its artistic decisions, but we do not know if these explanations are connected to its process of creation or merely a post hoc justification. Like Chinese export porcelain or the iPhone, we may describe an AI artwork as well-crafted, but it is difficult to comment artistically on it.

The assumed indistinguishability between AI and human art cascades this effect to all art. It is already difficult to identify artwork in a modern art exhibit. With the deluge of AI art, if we can’t determine if artwork is made by a human artist or AI-generated, we may tend to assume the latter. Without trust that the artwork was actually created by the artist, his frenzy and piety can easily be dismissed as AI generation. If so, why bother contemplating the design of a particular piece of artwork or obsessing over its singular truth, when it could be treated as one-of-many replaceable object for consumption? At the end of this process, art would be either made for the artist alone or interpreted as art by the audience alone. The artist and audience are divided. The artistic value may still remain, but no one is there to perceive it.

As our means of production advance, the social and artistic values of art have grown separate. We come to a bifurcation of art into crafts, oriented purely toward social popularity, and individualistic art, made for the indulgence of the single artist-audience. The future of art lies in the resynthesis of these two values through a return to friendship between the artist and his audience as the foundation of art. It rests in small groups of artists, where the distinction between human and AI art can be enforced through mutual trust. Only then can artistic value be restored and public art that is not conformist reconciled with personal art that is not solipsistic.