Table of Contents

I’ve always believed that Stanford goes the way of the world, if only a little bit earlier. We were early to wokeism, and were early to antiwokeism. Now, we must move forward, and do so boldly.

I must preface by thanking the Review community for allowing me to lead what is undeniably an important institution, both at Stanford and beyond. To each member of staff, editor, alumni, and to those in the Stanford community who have supported us, I extend my deepest gratitude. The Review has been the defining experience of my collegiate career, and I could not have asked for a better group to spend time with, to challenge my beliefs, and to confirm my conviction in all that a small band of ragtag rebels could accomplish if they put their mind to it.

This volume has much to be proud of, from exceptional new writing talent to the most-read article in the Review’s nearly forty-year history. I can only hope these accomplishments are thoroughly surpassed by my successor, Elsa Johnson. Having worked with her closely throughout her tenure as managing editor, I am confident she will do an exceptional job leading the Review.

This year, 2026, is the two-hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the American project, the story of another band of ragtag rebels who dared to dream boldly. Upon such a milestone, it is worth reflecting on the origins of our young nation and even younger university, and what the future may hold for both their intertwined fates.

Though a Stanford education demands minimal required reading, a baseline understanding of John Locke was asked of me–this is where I shall begin. Many have argued that there is no more visible a representation of Locke’s ideals than the United States and the world it has crafted–I am inclined to agree. Locke’s simple prescription of “life, liberty, and property” was augmented to Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This, of course, implies, as American history regales, that the pursuit of happiness is tantamount to the pursuit of property.

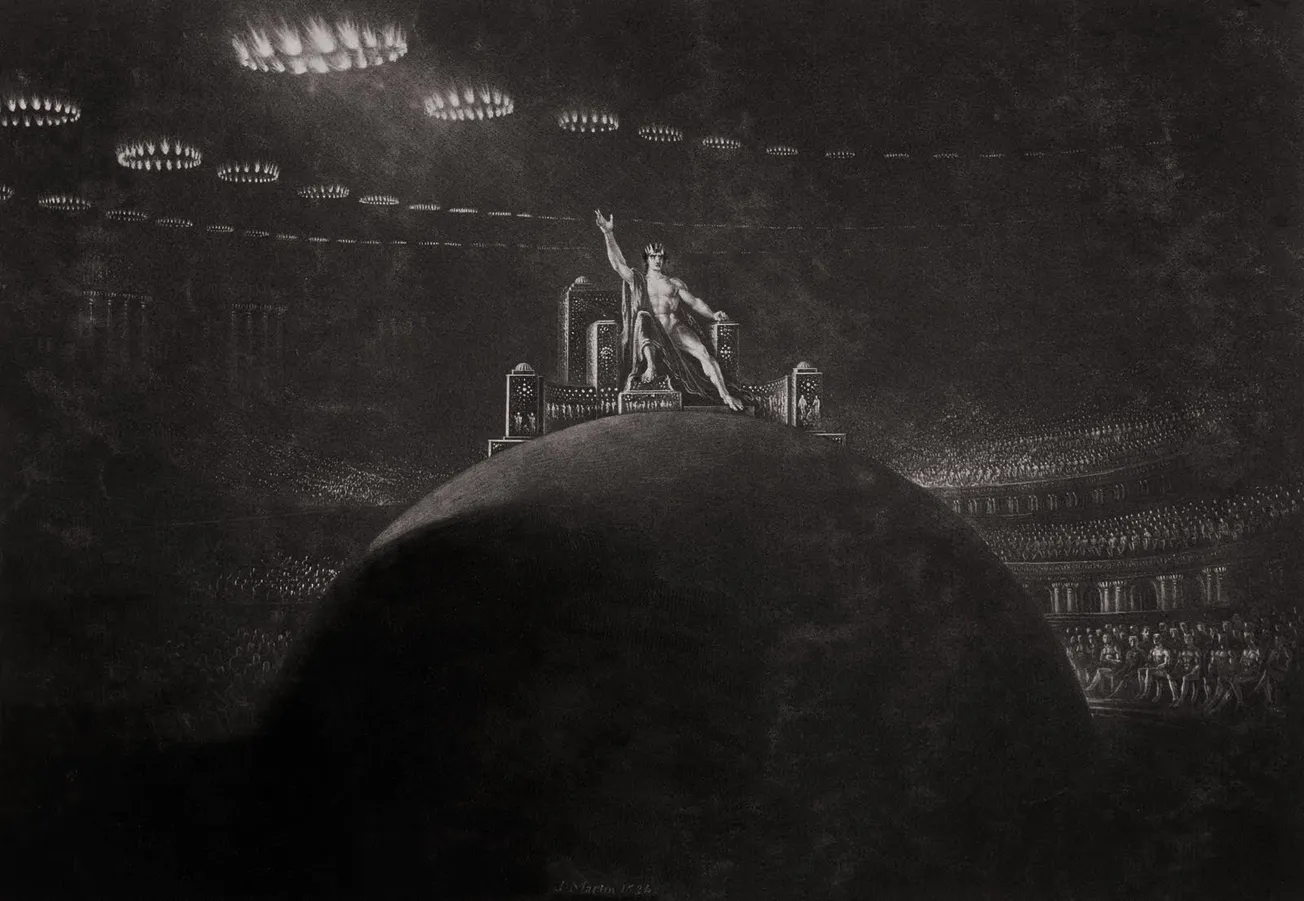

Stanford, born a century after the revolution and unshackled from the religious mores of its eastern counterparts, embodies the essence of Locke’s America. Here, “prostrations to the Gods of the Market-Place,” as Kipling put it, are far more common than to the “Gods of the Copybook Headings,” those guardians of ancient knowledge.

From its founding by a Robber Baron to its captains of industry in modern times, Stanford has been geared towards the commercial for the entirety of its history, and has exploited this direction with remarkable success.

Perhaps it is better for the Stanford student, the Enlightened man, to concern themselves with their classes and their startup rather than to question the unnatural order. Only in such a world could the teaching of Western civilization be condemned; what use is debating ancient questions if the productive result of said debates is never called upon in one’s life?

Stanford has long been a home for applied knowledge rather than merely the theoretical, but when it comes to the knowledge needed to not only thrive but also merely survive in this new world, the Stanford student is left empty-handed. Thankfully, these questions are not forgotten at the Stanford Review.

Our plight is rather Miltonian, walking around what can only be described as Paradise, bursting in the most literal sense with the fruit of nature, but our Paradise, as real as it may feel to the senses, has forgotten how to ask difficult questions, much less answer them. These questions, however, do not simply disappear. As Kipling concludes his poem, “The Gods of the Copybook Headings with terror and slaughter return!”

And return they have. Questions of the viability of our commercial system now ring from lips on both the political left and right. The property Locke so fondly spoke of is now being seized by a government once designed to protect it. Your property is now a prerequisite to others’ pursuit of happiness.

The Stanford computer science major, the thoroughbred of the Enlightenment project, devoted exclusively to conquering the commercial expanse, has succeeded in his endeavour with such finality that he now finds himself at risk of extinction through automation. And now these questions, of which God to worship when the God of the Marketplace disappears, questions once reserved for those fringe societies excluded from economic surplus, are entering the minds of the world’s most prosperous.

But I remain bright-eyed in these dark times, particularly for the youth of Stanford. My favorite place on campus for reflection is a circular bench near Main Quad. Within it, the following quote is inscribed:

“For the troubled, may you find peace. For the despairing, may you find hope. For the lonely, may you find love. For the skeptical, may you find faith.” – Frances C. Arrillaga

Certainly at Stanford, and at the Review, hope is palpable.

Though the road forward, to two-hundred-and-fifty more years of America and of Stanford, is exceedingly treacherous, with care and effort, both survival and success are possible.

At the core of the Review is asking questions others are unwilling to discuss. The continued prosperity of the American project depends on this, and as more begin to question, I hope the Review welcomes them with open arms. That these questions have not been wholly forgotten makes me optimistic that a positive future for the West is still possible.

Last commencement, President Jonathan Levin borrowed from the founder of Stanford’s creative writing program, Wallace Stegner, remarking that, “One cannot be pessimistic about the West. It is the native home of hope.” While the future remains in the balance, for the Review, for Stanford, and for America, I cannot help but be hopeful.

Fiat Lux,

Abhi Desai

Editor-in-Chief, Stanford Review Volume LXX