Table of Contents

I think if I told my freshman self that I would be leading the Review, she’d faint.

I’ll explain:

I came to Stanford as a card-carrying progressive (well, I didn’t have a card, but I had a Bernie t-shirt and a matching poster).

At my first club fair, I dutifully signed up for the Stanford Democratic Socialists of America and the now-defunct, leftist Stanford Sphere.

Somehow, I stumbled into my first Review meeting that winter after speaking with staffers in PHIL 49 about the moral obligation to vote, the interactions between globalization and technology, and the lack of open debate on campus.

With each meeting and each debate, I fell in love with the Review community. I found a place where all ideas were taken seriously. Where rigorous debate was an expectation, not a threat. Where history was examined with rigor, not shoehorned into a pet ideology. The Review became my place, my home on campus.

And, now, I couldn’t be prouder to lead it.

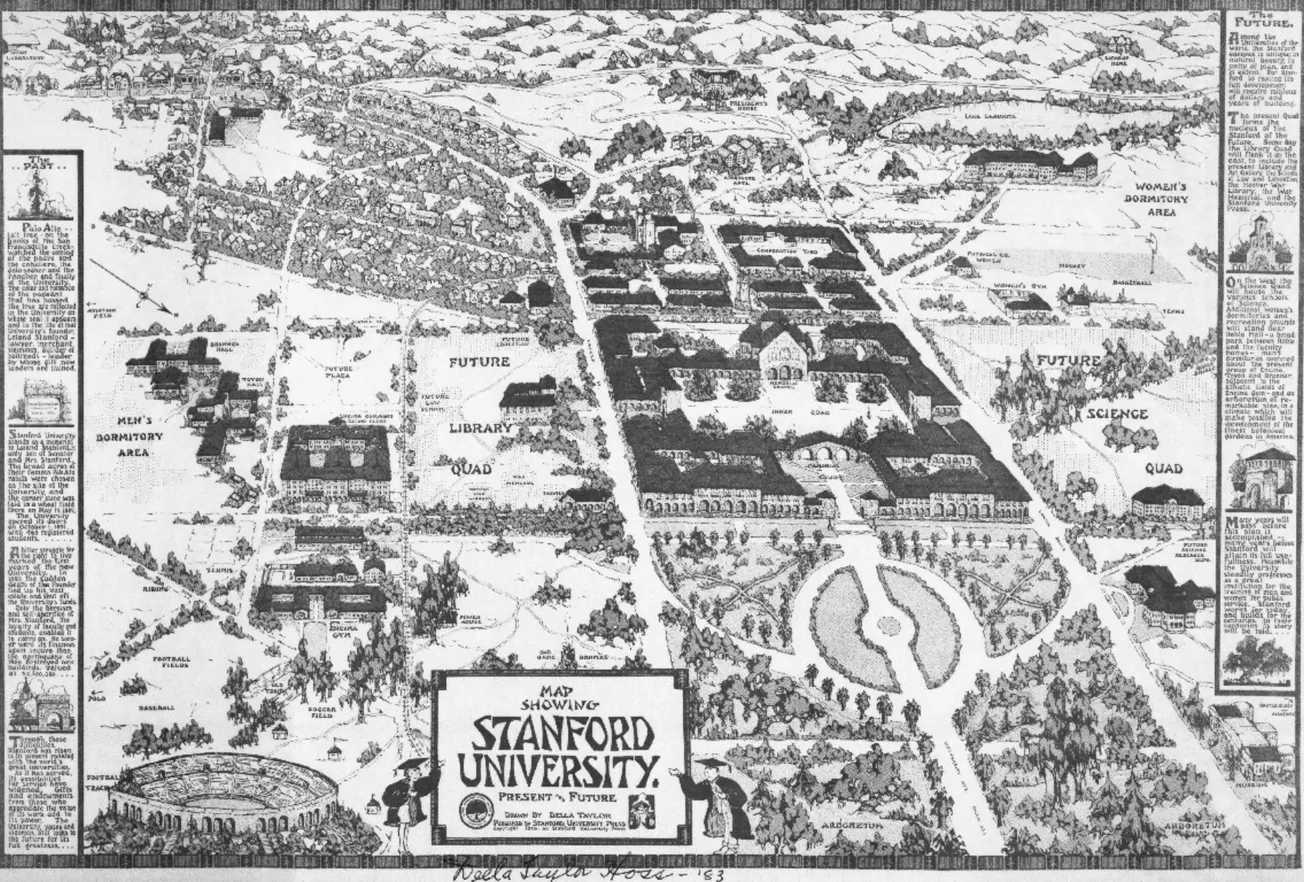

Stanford students founded the Review in 1987 to respond to their peers demanding the end of the ‘Western Civ’ program which taught great authors like Aristotle and Dante. Ultimately, the student protesters who chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, Western culture's got to go” were successful.

Western Civ’s replacement, now in its nth iteration called College, only requires students to read articles instead of books and is graded on completion, not hard work, comprehension, or excellence.

The students who led the charge against Western Civilization in the eighties are now leading universities like Stanford. The inmates have taken over the asylum.

Now, I’d guess that the majority of students who graduate from Stanford don’t read more than three books cover-to-cover for class in their four years here.

The echoes of “Western culture’s got to go” have been amplified and contorted, replaced by an outright rejection of the lowercase-l liberal project of open discussion, free speech, and a marketplace of ideas.

I know I am not alone in ‘waking up’ to the excesses of left. From having to wear a mask to walk to the bathroom to brush my teeth my freshman year to hearing my classmates cheer for terrorist organizations without shame to studying in a library that, for over a year, displayed a massive banner calling for violent revolution (“No Justice, No Peace”), I was in for a rude awakening.

This time, it’s not just students who support the radical, anti-liberal project. Stanford’s professors and administrators have played an active role.

Administrators forced student journalist Edwin Dorsey out of campus housing after he exposed the wrongdoings of members of Stanford’s Board of Trustees.

Administrators stripped one of my favorite professors in the Comparative Literature program, Professor Joan Ramon Resina, after students in the class complained that he was overly harsh on their identitarian literary analysis. The department chose to give all students ‘A’s in the class, despite their not attending.

Kairos, a house owned and administered by Stanford, said that to live there, students must believe in the “community value” of “Free Palestine”—while administrators have subjected almost every sorority and fraternity at Stanford to an arcane punishment system that disciplines students for the slightest transgression.

Stanford, despite encouraging citizenship and democracy via its new College class, suppressed the speech of anti-Israel activists by shutting down their sit-in the week before Family Weekend.

After Stanford Law School students told conservative judge Kyle Duncan that they “hope [his] daughters get raped,” an administrator sided with student agitators by encouraging them to shout down Judge Duncan.

Professors in the Department of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages barred students from hosting a reading group event on Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben because he was guilty of “COVID-19 misinformation.”

I could go on.

The Stanford Review exists as a countervailing force to dogmatism of all stripes. But perhaps more important than our investigations, interviews, and opinion pieces that dominate discussion on campus, the Review has become a haven for young writers to flourish. I know the Review’s impact is felt for all of my friends—close friends—who have sat in Old Union Room 215, debating our hearts out.

In Volume LXIX of the Review, I hope to show that there is room to push back against the groupthink that has taken over our institutions, including right here at Stanford.

We will cover the excesses of the radical, anti-pluralist ideology that has captured our institution.

We will cover how Stanford students continue to react to the Israel-Hamas war and, in turn, how the administration will respond to the protesters.

We will cover the new Free Speech doctrine (a change the Review welcomes) and Stanford’s incoming president, Jonathan Levin.

We will cover Stanford’s cooling relationship with Silicon Valley.

Personally, I’m most excited to cover the election—the first on college campuses in eight years—and its aftershocks.

Most of all, the Review will be steadfast in its defense of intellectual freedom. Expect to read a variety of perspectives, some of which you will disagree with.

….

I hope my nineteen-year-old freshman self would be proud of me for questioning my beliefs, even when doing so led me away from habit and convention.

For Stanford students interested in doing so: come to our weekly meetings, 7pm on Mondays, in Old Union (though our first meeting will be at Green Coupa). We’d love to have you.

Julia Steinberg

Editor-in-Chief, Volume LXIX

If you want to support the Review, you can subscribe to our free mailing list or make a donation. Email eic@stanfordreview.org with any questions.