Table of Contents

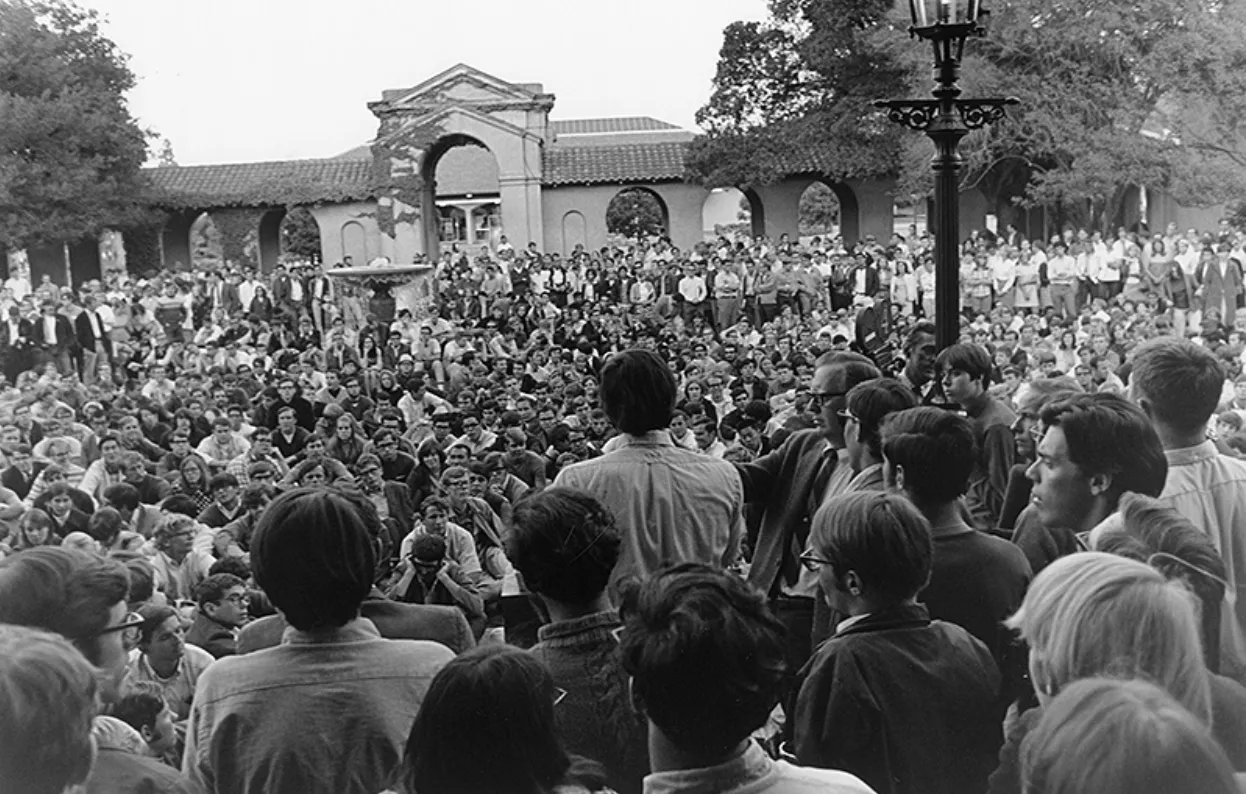

*Justice Delayed is Justice Denied! *Last June, hundreds of students gathered in White Plaza holding signs with phrases similar to this one to protest Stanford’s sexual assault policy. The students called both for quicker and for harsher punishments, highlighted by a demand for mandatory expulsion for those found guilty of sexual assault under Stanford’s Alternate Review Process (ARP). The ARP is Stanford’s judicial process designed specifically to investigate sexual assault claims. Since last spring, the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) has worked on a reform proposal that it plans to present to the student body and President Hennessy during fall quarter. A widely circulated draft of this proposal calls for the ARP to adopt expulsion as a default punishment that can only be avoided in rare circumstances.

Stanford’s ARP is different from a criminal trial as victims still have the opportunity to pursue criminal charges against their alleged assailants. Instead, the ARP is designed to fulfill Stanford’s Title IX obligation to investigate sexual assault in order to receive federal funding. Schools found to be noncompliant with Title IX, the federal law designed to stop gender discrimination in education, can be stripped of federal funding.

In 2011, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) forced colleges to adopt a preponderance of the evidence standard in sexual assault cases. This standard requires that the evidence proves that the accused is “more likely than not” guilty. *Preponderance of the evidence *is the lowest standard of proof in America’s judicial system and is mainly used to award monetary damages in civil cases.

Sexual assault is a terrible crime and Stanford should do whatever it can to assist victims. However, the combination of default expulsion and the low standard of proof in these cases coupled with high levels of public pressure to investigate assault significantly endangers students accused of sexual assault. Although ARP investigations are not criminal trials and constitutional due process is not legally required, both the severity of the punishment and the basic principles of justice demand that we consider due process to ensure only those guilty of sexual assault face punishment for it.

The fact that the debate has centered on the nature of punishments doled out to perpetrators should serve as a signal to consider due process concerns. Stanford should not rush to embrace default expulsion before the federal government raises the standard of proof.

The OCR and Preponderance of the Evidence

When the OCR forced schools to adopt a *preponderance of the evidence *standard in 2011, it justified the change by citing the standard’s usage in private Title IX civil suits. It also described how “OCR’s Case Processing Manual requires that a noncompliance determination be supported by the preponderance of the evidence when resolving allegations of discrimination under all the statutes enforced by OCR, including Title IX. OCR also uses a preponderance of the evidence standard in its fund termination administrative hearings.” All of these examples apply to funding issues when the OCR determines whether a school engages in discrimination, they do not reference individual findings of guilt for students.

The decision to potentially revoke funding from a school is fundamentally different from the decision to find an individual student guilty of an offense that will result in harsh punishment. These differences warrant a higher standard of proof for individuals for one main reason. The examples above as well as all Supreme Court case law on Title IX that uses preponderance of the evidence involve collective responsibility at the institutional level. Sexual assault Title IX proceedings involve culpability at the individual level. As described in further detail below, a finding of guilt can have severe consequences for the perpetrator that extend beyond the monetary damages present in institutional compliance cases normally tried under Title IX authority. A higher standard should be used because of this difference.

The civil case logic does not add up either. InAddington v. Texas (1979), the Supreme Court described how a preponderance of the evidence standard is best used when “society has a minimal concern with the outcome” of a private suit. It is clear by the widespread attention sexual assault has received that society has more than a minimal concern with the outcome of sexual assault cases. The opinion continues to explain that usage of a higher standard, such as clear and convincing evidence, is appropriate when “interests at stake in those cases are deemed to be more substantial than mere loss of money.”

Not only is the OCR’s official justification for the preponderance of the evidence standard inconsistent, there is established Supreme Court jurisprudence that contradicts this policy.

The ASSU Reform Proposal

The most prominent element of the ASSU’s reform proposal is default sanction of expulsion. Although the proposal does say that special “mitigating circumstances” may reduce this punishment, it provides neither examples nor guidelines as to what these circumstances are. Furthermore, it establishes that “mistaken consent” can never be a mitigating circumstance.

This elevated punishment in the reform proposal hinges on a violation of Stanford’s definition of consent. It states, in part: “If a person is mentally or physically incapacitated or impaired so that the person cannot understand the fact, nature, or extent of the sexual situation, there is no consent; this includes conditions due to alcohol or drug consumption or being asleep or unconscious.”

On the surface, this definition of consent seems logical: if someone is passed out and intoxicated then clearly he or she cannot give consent. However, accepting this definition is to acknowledge that sexual assault occurred even when common sense would state otherwise. Consider a couple that has been dating for three years where the man has been struggling with depression and under the emotional weight, has not told his girlfriend. According to the Mayo Clinic, there may be physical changes in brain structure that cause the man to have “trouble making decisions, or trouble thinking or concentrating.”

If a clinically depressed man has trouble thinking through decisions due to physical issues with his brain but decides to have sex with his girlfriend**,** did the man give consent? Must he be required to take corrective medicine to have the ability to fully “understand the fact, nature, or extent” of a sexual situation? It is clear that clinical depression affects how people perceive themselves. If we use Stanford’s definition of consent, then the woman has sexually assaulted her boyfriend who, unknown to her, is clinically depressed and unable to clearly understand situations and make decisions. This example depicts how a categorical prohibition against “mistaken consent” as a mitigating factor is overbroad, especially given the low standard of proof necessary to establish guilt.

Stanford’s definition of consent used to judge whether assault occurred has other problems. First, does the term “drugs” denote only illegal drugs or does it also capture medicine that may even slightly alter one’s mental processes? Webster’s dictionary contains both definitions and the medical one is listed first. Second, the word “includes” indicates that conditions are part of a list but that they do not comprise the entire list. What other conditions can make a student unable to understand the complete nature of a sexual interaction? Is this understanding categorical or is there a threshold on a continuum of understanding that must be met? What other criteria can we use to assess these conditions? Third, what if a potential sexual partner is unable to observe that a student is unable to give consent? Should a student be liable for this information asymmetry if the condition is “invisible”? The vagueness of this definition was likely intended to protect those who have been assaulted, but it has unwisely created a situation in which the ARP could find a lack of consent in a huge number of scenarios where no assault occurred. This is especially troubling given the immense pressure schools are under to investigate assault, the low standard of proof, and the default expulsion that mistaken consent cannot mitigate.

Finally, the proposal calls for increased training for panelists on the ARP. However, if Stanford’s current training is any guide, increased training may serve only to further bias panelists against the accused. A nonprofit organization called the Center for Relationship Abuse Awareness counts the Stanford University Judicial Affairs Department and Stanford’s PHE Program as two of its clients for training.The Center even singles out ARP panelists and Stanford several times on its training page. The organization describes online how to screen for abusers. According to the organization, an abuser will “act persuasive and logical”. A training system that believes a logical and persuasive defense to be a sign of guilt while simultaneously claiming to equip ARP panelists to be impartial is preposterous at best. It is an embarrassing tragedy that Stanford, a school that prides itself on research and inquiry, embraces training that teaches its judicial system to reject logical appeals in an emotionally charged issue. Stanford should reevaluate its procedures and training, not double down on them.

Conclusion

It is certainly understandable why there is immense pressure to use all measures, including harsher punishments and lower standards of proof, in an effort to convict assailants and deter others. It is very difficult to win a conviction for sexual assault in the criminal justice system for many reasons. For many victims of sexual violence, a school’s judicial process can be the only recourse available. The failure of the criminal justice system to address sexual violence is an incontrovertible problem, but the federal government, Stanford, and my classmates err by using Title IX to run around the criminal justice system. Instead of imposing default expulsion based on a flimsy evidentiary standard, Stanford should take the lead in advocating for reforms in the criminal justice system that will enable victims to better pursue justice while safeguarding the protections for the accused that form tenets of American ideals about justice. Until the federal government removes the standard of proof requirement or raises it to a higher standard, Stanford should not accept any proposal that promotes expulsion as a default punishment.