Table of Contents

By Lisa Wallace and Alex Atallah

By Lisa Wallace and Alex Atallah

In 1987, a group of Stanford undergraduates dedicated to a common mission founded The Stanford Review—to inspire campus debate by “presenting alternative viewpoints.”

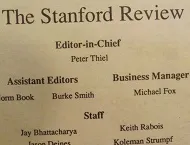

These students, led by Peter Thiel, the first editor-in-chief and founder PayPal, argued that campus discussion was dominated by a partisan few who both alienated and misrepresented a more moderate mainstream.

Though their goal was simple, The Stanford Review has a storied history. In the following years, the Review stayed true to its founding contrarian ethos, publishing articles and editorials that continually pushed the envelope of a traditionally liberal campus press.

The paper only existed during the eighties for a few years, yet the “Reagan Revolution,” with its Renaissance of free market values and classical conservatism, was influential to the outfit’s earlier conservative positions.

In the first few issues, the Review published articles questioning topics as diverse as the distribution of university-purchased condoms on campus, general education requirements, and the political language of “partisanship” and “political correctness” disrupting authentic dialogue.

In an open letter to Stanford University, Review staffers expressed disapproval of the fact that the Reagan Library did not come to Stanford because of the shaky relationship between Stanford and the Hoover Institution.

The letter audaciously and articulately called out the University’s tenuous relationship with conservative institutions, namely, the Hoover institution, saying “…these students and faculty who would gladly see the tower go, would cast away some of the most brilliant minds—regardless of their political perspective—in our university, along with one of the richest set of archives in the entire world.”

Equally bold claims were leveled at the university for the new, allegedly politically-correct structure of general humanities requirements, with classes entitled “CIV” replacing a Western Civilization requirement.

“When the outside world learns that Aristotle, Dante, Locke et al…have been replaced here by minor writers chosen for blatantly left-wing political reasons, our reputation will drop even lower,” wrote Mike Iwan and Norm Book in 1988.

Criticism toward liberal bias in curriculum development and in university admissions were hot-button issues in the eighties and moving in to the early nineties. Satirizing the misuse of political correctness, Adam Lieberman published a short guide to “partisanship” on Stanford’s campus, arguing that under Stanford’s definition of partisanship, it was considered “partisan” to fund anti-Marxist Nicaraguan Contras, but “non-partisan” to volunteer in guerrilla campaigns in El Salvador.

Naturally, such courageous challenging of the accepted discourse garnered more than a fair amount of criticism, but that was the publication’s goal. In a previous interview with the Review, founder Peter Thiel stated, “We thought it was fair to give the other side of the debate a fair hearing.”

The early 90’s saw debates surrounding free speech on campus. At one point, Robert Corry and Aman Verjee sued the university over the university’s policy surrounding a restrictive speech code. The Review staff members eventually won the case, marking a capstone of sorts for the free speech battles waged in the 90’s. In a 2010 interview about this time period, David Sacks, editor-in-chief of the Review and COO of PayPal, told the paper: “I certainly think it made the outside world much more aware of what was happening at Stanford.”

In the mid-90’s, the Review sought ways to take on a lighter tone, featuring imaginary opinions from Ronald Reagan about the Stanford community in a special section titled “Reagan Country.” “Cowboy Ron” would comment on aspects of Stanford life ranging from dorm-cest to the major in economics.

“If you’re gonna hook-up, the worst cowgirl to do it with is someone in your dorm,” he said in an issue from September 30, 1996. “But hey, at least you’re hooking up with someone.” His comments typically represented more conventional views from Reagan, such as Cowboy Ron’s approbative opinion of Stanford’s economics major, written on November 4th: “Sure, it’s not the ‘80’s anymore (Ahh…), but you can still sign up, sell out, and cash in—just major in economics. Forever Gordon Gekko and supply-side!”

The Review also became interested in the surge of conservative groups on campus that followed the GOP’s success in the 1994 U.S. midterm elections. In an article from November 4, 1996, staff writer Jay Sheth wrote about the Stanford College Republicans boosting membership from 100 to 300 in a year dedicated to supporting the Republican presidential candidate, Bob Dole.The groups also promoted Prop 209, an amendment that California would later pass to prohibit hiring discrimination in the public sector.

Later, in 1997, Stanford began debating whether to bring back the Reserve Officer Training Corps program. The college-based program to train U.S. armed forces was banned in the Vietnam War era anti-war climate and remained banned with the military’s 1993“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy against gays serving openly in the military.

In a February 3 editorial, the Review Editorial Board argued that this ROTC protest was ineffectual and constituted “selfish elitism.” Moreover, the writer pointed out that while many opponents were concerned with ROTC members undeservedly receiving academic credit, the university had an existing practice of giving credit to football players and band members which seemed consistent with ROTC members receiving the same. These contrarian viewpoints publicized in the Review helped challenge the predominate assumptions made on campus, and the Stanford Faculty Senate ultimately voted to bring back ROTC in 2011.

Today, ASSU and national elections continue to be a widely-covered topic by the Review, in addition to topics like Greek life and changes in university policy. In an early editorial entitled “Rethinking Financial Aid,” Peter Thiel criticized increases in Stanford University tuition that were per year consistently higher than the rate of inflation and of personal income growth. Thiel explained, “A record 70% of Stanford undergrads must now receive some form of financial aid. Or, put another way, since Stanford is already too expensive for 70% of its students, all the real increases must be levied on the remaining 30%.”

Thiel pointed out the paradox that continues to occur with tuition increases in private education, “the increases tend to decrease the percentage of students whose families can pay, which in turn requires proportionally greater real increases on the ever-decreasing base.” As much as shiny new buildings and extravagant meal plans sweeten matriculation for the best and brightest admitted students, today it is not a wholly unfamiliar phenomenon for students in the middle class to be dissuaded from accepting tuition.

Throughout its history the Stanford Review has remained true to its founding mission, publishing articles that steer campus dialogue away from the safe and into a conversation that promotes rational argument and the consideration of all viewpoints.