Table of Contents

I still support police and prison reform, but the event last Monday night made me seriously question the movement’s tone and rhetoric.

Don’t get me wrong, much of the event was enjoyable. The panel, consisting of State Senator Maria Chappelle-Nadal, artists Tef Poe and David Banner, and CNN contributor Marc Lamont Hill, presented a powerful case for combating prejudice in policing and prisons. David Banner made a particularly salient point when he contrasted the police response in Ferguson to the police response to the Cliven Bundy standoff in Nevada. Banner pointed out that while Ferguson protesters were met with SWAT teams armed with tanks and tear gas, federal forces chose to disengage at Bundy Ranch when supporters took up strategic positions and trained their weapons on law enforcement officers.

“There is a difference!” Banner roared.

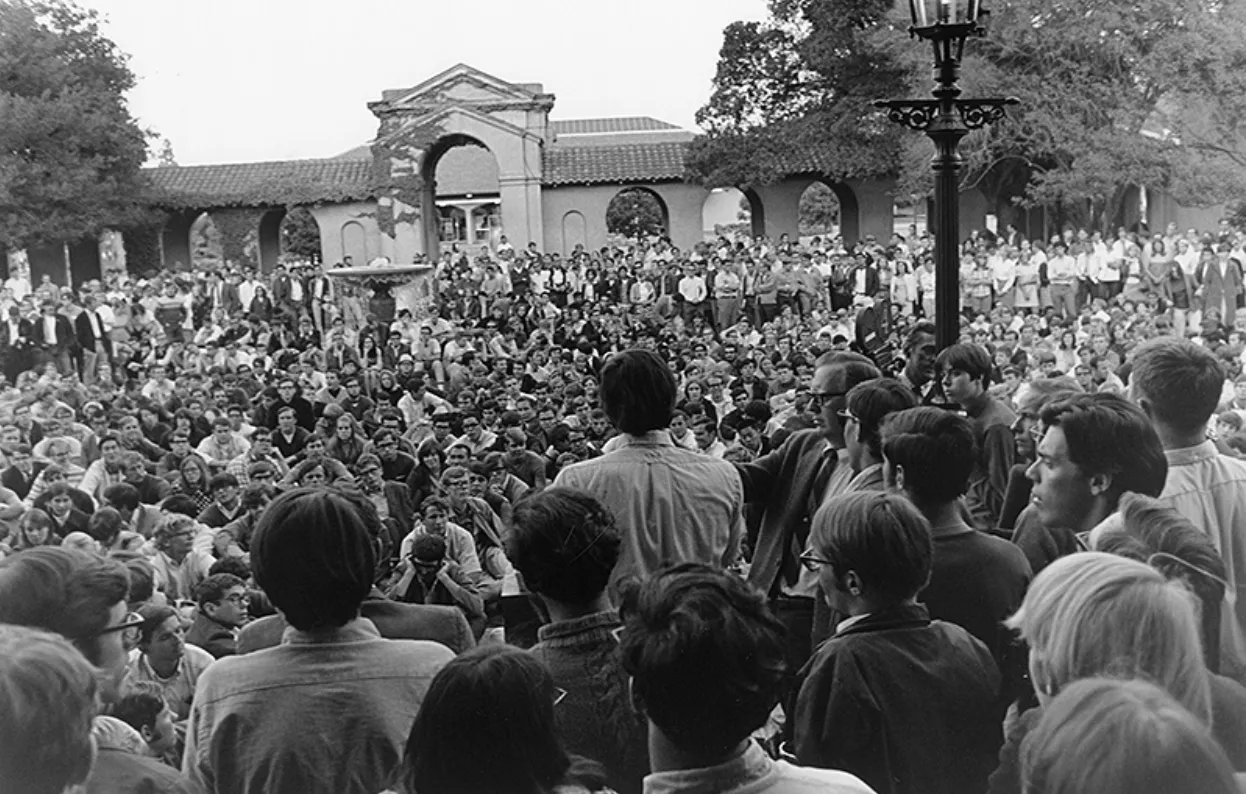

Ultimately, however, the meeting fostered an environment of uncomfortable political and racial exclusivity, despite the many questions participants asked regarding how to be more inclusive and garner widespread support for the cause.

“I would dare us to imagine a world after capitalism,” Hill challenged the audience at one point. “After whiteness. After prison.”

“How sincere do you think white liberalism is?” one student asked the panel, prompting a burst of applause and causing Tef Poe to leap off the stage and pull the questioner into a brotherly embrace.

Recounting her experience on the ground at Ferguson, State Senator Chappelle-Nadal complained about the dress of other congressmen and clergy who had shown up to Ferguson and been less than supportive of the protestors. “How *dare *you show up in your suit and your high heels while people are suffering?” she asked furiously.

Though nobody was calling me out personally, these remarks made me feel oddly targeted. Perhaps more so than at any other point in my life, I felt too white. Was my support for police and prison reform negated because of my “whiteness” and belief in free markets? Was I precluded from standing with the black community because I wore a suit? Did I really have to believe that “America is not sorry about slavery” (to quote David Banner) or that “there is no functional or healthy role for police in our community” (Lamont Hill) to believe that there are racial disparities in our legal system?

By repeatedly employing terms such as “whiteness” and emphasizing over and over again that nobody outside the black community could really understand their particular challenges, the panelists and participants left the impression that outsider help was either insincere or unwanted.

At times I even felt that I was considered part of the problem simply because of the color of my skin. I felt this particularly strongly when Tef Poe said he had to speak out against sexism because he was, by virtue of being male, “part of the ‘ism’, part of the oppressing party.”

Can I really be labeled as an oppressor for any reason other than my own beliefs and actions? It doesn’t seem a very fair or open-minded way to categorize people.

The whole situation was doubly uncomfortable because Senator Chappelle-Nadal had opened with a moving personal story about having been “put in a black box” her whole life by whites and blacks, Republicans and Democrats alike. Sadly, and rather ironically, elements of this racial pigeonholing surfaced just minutes later.

When Chappelle-Nadal pointed out that rural white communities were also experiencing police harassment and that representative policing alone was not a solution to police brutality, she didn’t earn many claps or snaps. The scattered applause or outright silence that followed some of Chappelle-Nadal’s even slightly unorthodox comments were painfully obvious. Admirably, she still had the integrity and bravery to end one answer with, “Republicans at this point have more compassion than my own party in my state.”

I understand that I can’t understand what it’s like to be black in America. As David Banner humorously pointed out, “One of the things I hate is when somebody tells me that the black experience ain’t that bad. That’s like me telling a woman, ‘Ah, pregnancy ain’t that bad.’ How the hell do I know?”

I also understand that this atmosphere of exclusivity was unintentional. But if our goal really is to win the support of as many diverse groups as possible in order to enact real policy reforms, putting people into stereotypical groups and making them feel that these problems are just ‘black issues’ is the wrong way to go about it. We need to get all kinds of people–black and white, capitalist and Communist, rich and poor–to understand that civil rights and liberties are important for everyone. We need to help others see that the misapplication of justice for any group is a danger to us all.

We can’t afford to apply superfluous racial and ideological litmus tests to those who want to be our allies. Since not all sympathizers have the exact same beliefs or political agenda, we should focus on the specific issues at hand and be sensitive to how others will perceive our tone and rhetoric. Let’s work on making the tent bigger, not smaller.