Table of Contents

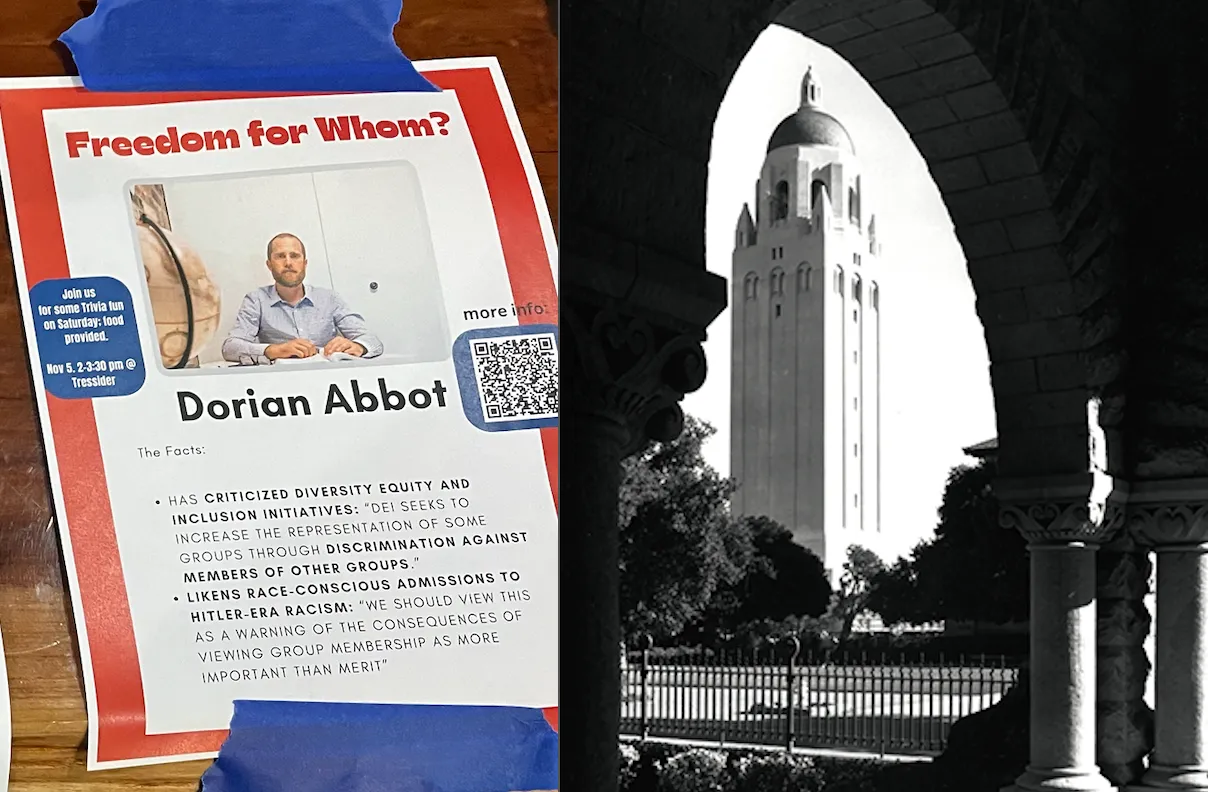

Last November, posters were taped around campus advertising a protest against the then-upcoming Academic Freedom Conference. “Freedom for whom?” the anonymous protesters asked, attempting to deny infamous scholars and thinkers their right to speak freely. This sort of behavior arguing the limitation of speech for those considered out of bounds is common practice for the campus left. What I did not expect is for Hoover to tacitly join in the protest.

A classic battle at Stanford’s campus is between Hoover and Stanford—scroll through the Daily’s archives for the latest updates in the perennial struggle. Despite this, Hoover’s name was suspiciously absent from last autumn’s trendy love-to-hate event amongst progressive professors and anonymous poster-makers alike. Ultimately, the event was hosted by the Graduate School of Business’ Classical Liberalism Initiative.

To learn more about the Academic Freedom Conference, I talked with some sponsors of the conference, even more Hoover Senior Fellows, and read documents detailing Stanford’s contractual relationship with Hoover. One Senior Fellow even remarked that, in my prior articles, I had “barely scratched the surface” of Hoover’s internal conflicts. To summarize, Hoover’s failure to sponsor the Academic Freedom Conference is one of many inflection points in the relationship between Hoover and what I will call ‘Stanford proper.’ Hoover is dependent on Stanford. Because Hoover’s institutional freedom is limited, its ideological freedom is, too.

In my first article covering the Hoover Institution, I wrote: “Hoover’s refusal to sponsor the event begs the question—why not?” No one I talked to could truly answer that question. I emailed Condoleezza Rice herself to ask why, and she directed me to an earlier statement given to the Review by Hoover spokeswoman Eryn Tillman, who had previously asked for the statement to be affixed to my previous article in this series. Her statement is as follows:

The conference program presented to Hoover on academic freedom was more political and less academic in nature and because organizers approached Hoover after the agenda was set, and invitations had gone out, there wasn’t an opportunity to help shape the program. Hoover conferences seek to find data-driven policy solutions based on empirical research, including academic papers that would substantively support the attacks on academic freedom that we are trying to counter. We agreed that Hoover would do a conference on Academic Freedom of the kind that we envisioned at another time. —Eryn Tillman, Hoover Spokeswoman

Aside from the nonsensical syntax in the response—I have no idea what “including academic papers that would substantively support the attacks on academic freedom that we are trying to counter” even means—the response is seemingly untruthful.

Dorian Abbot, one of the organizers of the conference and Associate Professor of Geophysics at the University of Chicago, told me that "the conference was academic in nature, with no politicians present or overtly political content. It is disingenuous to suggest that it was political."

I also find it strange that instead of supporting a pre-existing conference, led in part by Hoover Senior Fellow John Cochrane, Hoover decided to break from academic protocol in removing their support from a Senior Fellow’s academic undertaking. This response raised more questions than it answered.

Below is my explanation as to why Hoover did not support the Academic Freedom Conference:

Part I: A quick Hoover history lesson

The Hoover Institution was founded in 1919, thirty-four years after Stanford proper was established. It came into its current form under W. Glenn Campbell, who was appointed as Director at the recommendation of Herbert Hoover himself. Campbell wrote a memoir in 2000, The Competition of Ideas: How My Colleagues and I Built the Hoover Institution, that articulates the tensions between Hoover and Stanford proper and his time as the Director of Hoover from 1960 to 1989. He writes that Donald Kennedy, President of Stanford from 1980 to 1992, “took a very different approach” to the competition of ideas. Campbell—who built the Hoover Institution into a deeply influential think tank that powered the Reagan administration—summarized Hoover-Stanford relations as follows:

Over the years, in answer to questions about relations between Stanford and the Hoover Institution, I always replied that they were similar to J.P. Morgan’s description of the stock market: ‘They fluctuated.’ During the 1970s, while Richard W. Lyman was president, we had excellent relationships with the rest of the university, and more joint appointments were made than ever before or since. Compared to more recent Hoover-Stanford relations, our interactions overall were quite good—even while Wally Sterlin was president and during Kenneth Pitzer’s brief tenure. Not until the 1980s, under Donald Kennedy, did relations deteriorate, Kennedy used every available dirty trick against me, including salary discrimination and allegations about my personal character. —W. Glenn Campbell, former Director of the Hoover Institution

I was told that Campbell was forced out by Kennedy, citing personality differences and a dysfunctional relationship. The Hoover website refers to it as his “retirement.” Campbell’s memoir refers to it as “[Kennedy’s] systemic campaign to force my firing or resignation.” Ouch. Already, there is a historical precedent for Stanford’s administrative control over Hoover or, at the very least, tensions between Hoover and Stanford proper.

John Raisian took over the role of Hoover’s Director in 1989, after being selected as the Interim Director by Donald Kennedy. He stepped down in 2015. His successor Thomas Gilligan served a five year term before Rice took over as Director in 2020.

A Senior Fellow who requested anonymity for fear of retribution told me that Raisan “had to walk a fine line to maintain Hoover’s independence.” It seems he instead cemented Hoover as subservient to Stanford proper.

During Raisian’s tenure, Hoover’s Board of Overseers approved its new bylaws, dated June 9, 2011. These bylaws that outline Hoover’s chains of command and Hoover’s relationship to the university are the most recent and, as follows, govern Hoover to this day. However, these bylaws are not publicized, meaning that Hoover’s governance is shrouded.

Article 8 of the bylaws—the final article—concerns the role of Stanford proper’s board of trustees. It reads as follows:

It is evidently clear that Stanford proper wields “ultimate” control over Hoover. Read Article 8 and read it again. Hoover’s structure makes it both de facto and de jure subservient to Stanford proper.

Part II: The Academic Freedom Conference

I was told by Ivan Marinovic, Assistant Professor of Accounting at the Graduate School of Business and member of the Conference’s Organizing Committee, that Hoover made a tentative commitment to sponsor the Academic Freedom Conference. As echoed by other organizers of the conference, Hoover’s support was to encompass both financial support as well as the use of Hoover’s space on campus to host the conference itself. Professor Marinovic told me that the Graduate School of Business was able to give around $50,000 and that he expected that Hoover would give a similar amount. But unlike the GSB, Hoover pulled out and did not give any money for the conference.

At the time, this posed an existential threat to the Academic Freedom Conference itself. Without Hoover’s money or space on campus to host the event, it would be impossible to host it. Hoover’s withdrawal nearly killed the conference. Thankfully, private donors stepped in and the conference was hosted as planned, though without Hoover’s institutional involvement. In Hoover Senior Fellow and conference organizer John Cochrane’s opening remarks, he alludes to “turbulence” in planning the conference. Later on in his remarks, Cochrane plainly admitted that “even the Hoover Institution declined to support or co-host this conference, deeming it ‘too political.’”

Hoover was asked to give around $50,000, a large sum of money. But, for Hoover, it’s only a drop in the bucket: Hoover has recently shelled out millions on a new office building, one that will remain largely empty and useless upon completion as many Fellows don’t show up to their current offices. Hoover’s 2022 annual report gives us some key figures on Hoover’s finances: Hoover’s endowment market value is around $757 million and Hoover’s operating expenses for FY2022 were $77.6 million. Reneging on a $50,000 ask cannot be justified by budgetary concerns.

In my reporting, I was told about fearful whispers that the Academic Freedom Conference would associate Hoover with “a who’s who of self-proclaimed canceled academics,” an association that Hoover leadership wanted to avoid at all costs. If Hoover was seriously committed to its tagline about “ideas defining a free society,” the desire to host a conference about academic freedom and its importance would trump any concerns about optics. But, sadly, this was not the case.

Professor Marinovic spoke frankly with me when he expressed his frustration over Hoover’s “U-turn.” He said that “The fact that the Hoover Institution ultimately refused to support the conference was damaging for this event initially because, as you would expect, it made the conference look like a fringe conference that the Hoover Institution wouldn’t support.”

It makes perfect sense that Hoover wouldn’t want to associate itself with a fringe group of radical free speech activists if it meant diminishing Hoover's reputation in the university proper. I was told about how liberal professors who were invited to the conference declined, citing fear of affiliation with more controversial attendees. A source close to the planning of the conference explained the logic of cancellation as follows: “Well I can’t be seen talking to this guy because this guy talked to that guy and that guy published that article and that journal published an article with a guy who went to a Trump rally.”

If academics who supported academic freedom were unwilling to go to the conference for reputational reasons, it is logical that Director Rice would do the same. This same source agrees: “it’s rational to be concerned about being too provocative, but Rice was too willing to sacrifice important principles for fear of minor backlash in this case.” Thus goes the sad irony wrought by the Academic Freedom Conference.

Wokism isn’t just an abundance of pride flags or appeals to victimhood. It is an attack on the freedom to express oneself. We’ve seen how the logic of cancellation—one of the many logics of wokeness—causes even outspoken academics to crawl back into their caves, enacting cycles of self-repression that makes true and open inquiry impossible. Now, more than ever, Hoover must stand by its founding principles.

Luckily, the Academic Freedom Conference went on; videos of the conference are available to the public to watch here. But Hoover’s absence was noted—a think tank devoted to “ideas protecting a free society” in its actions excluded freedom of speech, perhaps the most essential of all its freedoms, from its domain. Director Condoleezza Rice and Hoover’s leadership have joined in Stanford proper’s long history of suppressing freedom of speech at Stanford, a wholesale abandonment of Hoover’s core values.

Hoover was founded to house an extensive collection of Soviet documents—I’m sure it wouldn’t take much digging in the archives of Hoover Tower to find proof for freedom of speech’s importance. To avoid another Academic Freedom Conference-type situation, I urge Hoover to assert its ideological independence and to stick to its core values that allowed it to become so highly regarded. If they don’t, donors ought to reconsider their financial sponsorship of an institution that rhetorically celebrates freedom but takes actions that suggest otherwise.

But, I’m afraid Stanford’s administrative capture of Hoover makes my hope all but impossible. In the meantime, it is the role of a free press to hold institutions accountable, and—thankfully—the Review is here to stay.

Quotations lightly edited for grammar and clarity

This article is the third in a series covering the Hoover Institution’s turn leftwards. If you want to stay tuned as more details come out, subscribe to the Stanford Review. If you have any relevant information about Hoover, send it to eic@stanfordreview.org. And to support the work we do, make a donation.